A lack of vitamin D can lead to brittle and painful bones, muscle weakness and a variety of health risks.

During summer, people are able to get about 90 percent of their daily requirements naturally through the skin by exposure to the sun. The remainder is consumed through foods such as oily fish or chicken eggs.

However, the challenge to get enough vitamin D increases in the winter when there are shorter daylight hours and a lack of sunshine.

Scientists have now found a way to increase vitamin D content in eggs by exposing lay hens to UV light.

Read Also

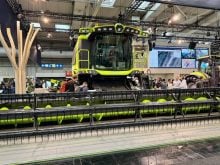

Agritechnica Day 3: Hybrid drive for a combine, data standards keep up to tech change and tractors of the year

Agritechnica 2025 Day 3: Hybrid drive for a combine, data standards keep up to tech change and tractors of the year.

At the Martin Luther University (MLU) in Halle-Wittenberg, Germany, a team of agricultural scientists and nutritionists used UV lamps in henhouses and focused the rays on the chickens’ legs, away from their feathers. They used two different chicken genotypes and stocking densities to find out whether different UV-emitting regimes worked under real indoor housing conditions.

They found a 3.7-fold increase in egg vitamin D content in Lohmann Selected Leghorn hens and a 4.2-fold increase in Lohmann Brown hens after three weeks of UV light exposure for six hours a day. Comparisons were made not only between chicken breeds but various lamps and different durations of light exposure during each day. However, the challenge was where to place the lamps for maximum exposure.

“The high density of the animals is challenging when you want to ensure an equal exposure of UV light for all individuals,” said nutritionist Dr. Julia Kühn.

“In my opinion, the best strategy to overcome these problems is placing the UV emitting lamps close to the feeders. Placing the lamps above the hens would be less efficient. In previous studies, we found that only the featherless parts of the chickens’ legs are able to produce vitamin D. Skin of feathered body parts contains only marginal amounts of vitamin D precourser (7-dehydrocholesterol). It is therefore important to place the lamps near the floor especially as the hen’s body would cast a shadow on the featherless legs if the light comes from above.”

She said that, in 2012, they performed several studies that investigated the concept of UV exposure to the vitamin D content of eggs and addressed fundamental questions concerning physiological parameters, optimal UV lighting regimes, the value of free-range farming, animal health and other issues including egg weight, eggshell thickness and cholesterol content of egg yolk.

Those studies were done under optimum conditions with one chicken per lamp. This latest study demonstrated that the concept of UV light works under practical farming conditions.

In the study, they compared a high stocking density of 12 hens per square metre with a low stocking density of four hens per sq. metre. She said that the experiment was performed on a commercial egg farm and that the hens were kept in furnished cages, sometimes called enriched or modified cages. They are cages designed to overcome some welfare concerns of battery cages yet still retain their economic and husbandry advantages. Kühn’s preference would have been to perform the experiment in a floor/barn system, but finances prevented them from doing a modified experimental setup. However, the experiments provided a high level of success.

“We did not find any side effects on laying performance or egg quality,” she said. “During this experiment, we investigated if hens avoid or prefer areas with higher UV intensity. But we found no difference in their habitat presences under UV light exposure.”

Chickens are tetrachromatic. They have four types of cones that let them see red, blue, and green light as well as ultraviolet light. And since their eyes are in the sides of their heads, they can use each eye independently on different tasks.

Kühn said that the light conditions in laying hen systems affect social behaviour and therefore the welfare of the animals. She said that the UV light reduces stress and feather pecking, a serious problem that can increase the risk of cannibalism. They did not find any detrimental effects on behaviour from the application of UV light exposure.

“Humans cannot see UV light, but chickens can,” said professor Eberhard von Borell in a news release, an expert in animal husbandry at MLU. “Therefore, light regimes are a critical aspect in chicken husbandry because light influences behaviour and laying activity.”

Chicken behaviour was analyzed using video recordings and the researchers inspected each chicken’s plumage for evidence of injuries by other hens to assess their potential for aggressive activity. But no problems were recorded. The hens neither avoided the area around the lamps nor did their normal behaviour change.

The study eggs were evaluated by a certified sensory panel. The UV eggs were identical to normal eggs and that same conclusion was drawn by visitors at two agricultural fairs where the eggs were put on display.

The researchers concluded that, given the practical methods used, the use of UV lamps represents an important step toward providing consumers with additional vitamin D.

The research paper ‘Feasibility of artificial light regimes to increase the vitamin D content in indoor-laid eggs’ was published recently in Poultry Science.