QUEBEC CITY – Canada has been losing agricultural markets to the United States during the past year because the U.S. has been doing an end run around world trade talks, says the chair of the Canadian Federation of Agriculture’s trade committee.

While Canada has been concentrating on reviving World Trade Organization negotiations since they stalled in Cancun, Mexico, last September, the U.S. has been negotiating one-on-one access deals with various countries, Saskatchewan grain farmer Marvin Shauf told the CFA semi-annual meeting July 29.

“The result is we are losing market share,” he said.

Read Also

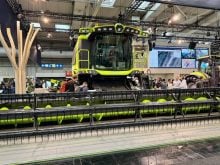

Agritechnica Day 3: Hybrid drive for a combine, data standards keep up to tech change and tractors of the year

Agritechnica 2025 Day 3: Hybrid drive for a combine, data standards keep up to tech change and tractors of the year.

“The Americans appear to be targeting Canadian markets, particularly in wheat and pork.”

Shauf proposed, and the CFA agreed, that the Canadian government should focus more on negotiating its own bilateral deals while not taking its eye off the WTO.

“Clearly the Americans are putting their efforts into negotiations outside the WTO and we are losing sales or value of exports as a result,” Shauf said in an interview.

“I think Canada has to follow the same path if we are going to compete.”

Although he said he would not identify countries that are negotiating separate trade deals with the U.S., an Australian-U.S. free trade agreement has been negotiated and others are in the works.

Shauf said it may not be a deliberate strategy to target Canadian markets, but since Canada trades into markets where it can make a profit, these would be logical targets for U.S. attention.

“I can’t really say there’s deliberate targeting but our markets are affected and the result is the same.”

Bilateral deals work to the U.S.’s advantage, he said. It can negotiate preferential access to an individual market without offering concessions on its own domestic subsidy or protection policies. In contrast, any market openings negotiated through the WTO come with the price of agreeing to greater discipline on domestic subsidies and protection.

In addition, the U.S. is in a far stronger bargaining position negotiating with one much-weaker country than it is trying to influence a WTO deal that must be accepted by 148 countries.

“It is very much in their favour,” Shauf said.