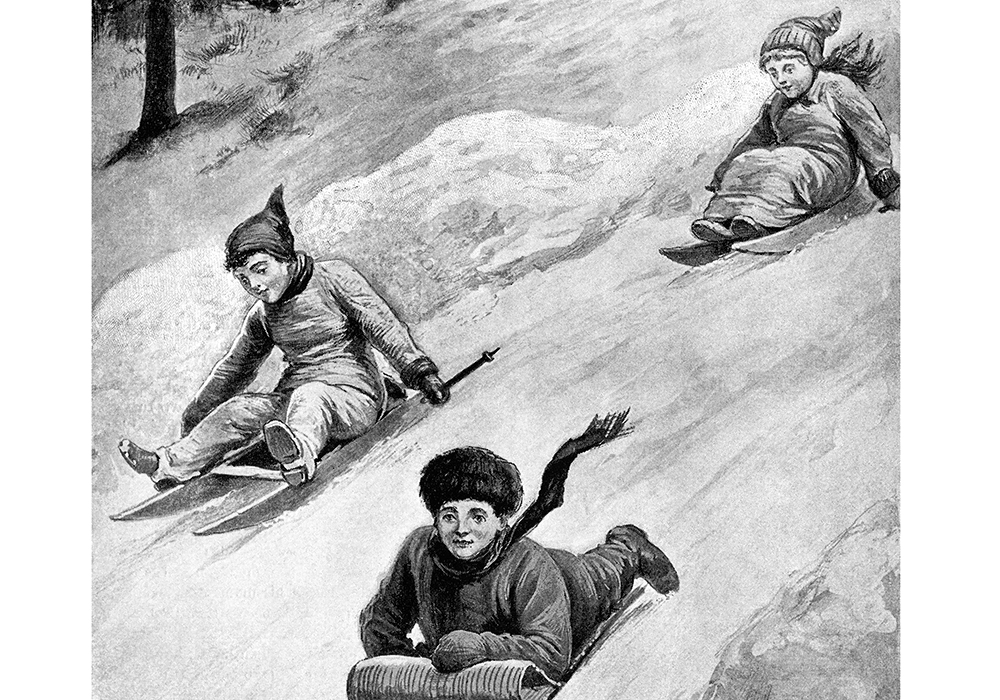

One day in particular remained something to remember, thanks to hard-packed snow, gravity and a polished ice surface

I’ve had my share of life’s downhill experiences: relationships, careers, black diamond ski hills, and skidding out-of-control cars.

They’re terrible. They can be dangerous. Yet there is one downhill run that I welcome — tobogganing.

I can’t explain it. In the deep mid-winter, my three brothers and I would walk endlessly in the cold and the snow to find a scouted hill, hike up it, pile onto a toboggan, aim it downhill, and let gravity grab hold. It was great.

Now tobogganing fun may be defined slightly differently here. To stand at the top of the hill, survey the unknown white expanse unfolding below, and entrust your well-being to narrow planks assembled with screws, nails and ropes — well, let’s just say it took a certain amount of bravery. The actual fun occurred closer to the end of the toboggan run, nearer to the bottom of the hill, and especially after a head and limb count revealed everyone was intact.

Read Also

Using artificial intelligence in agriculture starts with the right data

Good data is critical as the agriculture sector increasingly adopts new AI technology to drive efficiency, sustainability and trust across all levels of the value chain.

In the 1970s on our Manitoba farm, we had to embrace winter. It was long, cold, and occasionally, quite bleak. Winter was shades of white, colourless. Our choices were to stay inside the farmhouse, become bored, and begin to quarrel, or head outside, get exercise, and breathe in fresh air. Mother regularly herded us out the door.

At Christmastime in about 1969, a gift to the family had mysteriously appeared under the tree, a long toboggan. How Mom and Dad (a.k.a. Santa) had managed to keep that hidden from their six children, we’ll never know? Perhaps it was in the barn hayloft, stowed between rows of hay bales — you know, where Momma Cat hid litters of newborn kittens.

And off we’d trudge. We’d all be bundled up like little Ralphie’s brother in the movie A Christmas Story. Fashion was not a factor. We were warm and protected from winter’s icy chills.

The initial toboggan run tested us. We would have to break a trail, deal with overhanging tree branches, rumble over a hidden log, and crash through willow bushes at the bottom of the hill. Often, we’d have to scramble off (or get spilled off) and tramp soft snow to get to the bottom. We knew our reward would be the second run, or the third, or the 33rd one.

And we were always right. The oft-tested toboggan soon had polished boards on the underside, packed snow underneath, and a path resembling a bobsled run. Heeeeere we go.

We also had a two-person aluminium sled, which went even faster. We used it only after the route had been blazed and proven and after our fears had been forgotten.

I recall one mid-1970s expedition in particular. The lake on our farm’s southern side featured steep 150-foot high grassy palisades along one edge. We stared at them all summer going to and from the little hamlet of Basswood. What potential for winter thrills.

On that Sunday January afternoon, with ice frozen, likely right to the lake bottom (“that’s why there aren’t any fish in it,” Dad theorized), we took on the hill’s challenge. The wind had sculptured the snow, packing symmetrical drifts, nicely aligned at gentle downhill angles. Amazingly perfect.

Even the first run was good. The hard-packed snow with the drifts’ ridges, the combined mass of four farm boys, and Isaac Newton’s discovery of gravity, all served to deliver us surely to the bottom.

Then the unexpected happened.

The blowing wind, which had drifted the snow, had also polished the ice surface. When our loaded toboggan hit it, we seemed to speed up. A gas pedal on a toboggan? Huh? We shot out an extra 100 feet onto the glassy ice.

Plus, in the absence of friction, a moving object will continue to move (thanks again, Mr. Newton). And that meant scribing a slow sliding sideways circle.

We didn’t know much about physics yet, and we didn’t care. Whoever or whatever was tugging on the slowly rotating sled was our buddy. For the next run, the number four rider, maybe brother Tim, dragged a mitten and the toboggan turned faster. Too good.

It was a bobsled run that Olympians would envy.

Going back uphill was tough, but we soon tramped a trail. We needed time to analyze the situation anyway. And as seasoned adventurers, we had to discuss what had just occurred. I am sure Sir Edmund Hillary recounted his ascent steps at every rest stop.

My older brother David led the way. The thrill of the ride down out-balanced the effort on the way up.

Later, David scouted an adjacent drift that curved sharply near the top. We had brought a small shovel, and he carved a large, but short tunnel through the drift. His engineering skills delivered us in a straighter line, through the snow hole, onto the next drift, and down the hill. We ducked slightly. What bobsled run has a snow tunnel?

And with a slap of wood against ice, we still skittered out onto the frozen water as the winter world around us swirled slowly. We eventually exhausted ourselves, and the hours. The sun began to sink, spreading wide on the western sky. The winter day and adventure ended.

Plus my conscience began to nag me. Chore time.

Those beef cows demanded food, the few Holsteins needed to be milked, and Momma Cat would meow for her bowl of warm milk. Junior and Pups, our farm dogs, needed attention too.

We hurried home, chirping all the way. During the next week, we re-lived our escapade many times over. That we may have embellished the story is a given.

About 27 years later in January 2002, I caught up to my youngest brother Ron in Winnipeg. We drove back to the old farm with a toboggan in the back seat. We got to the area of the steep palisade and we tried to roll back time.

However, the thrill had vanished. The walk uphill was brutal. We sunk to our waists in the soft snow. And we complained about the cold. The fun was gone.

Still, that winter joy from our youth was firmly ensconced in our memories. And that was enough.