LETHBRIDGE — Frank Larney notices dry material swirling in the wind when he climbs on top of a fully cured compost pile at Agriculture Canada’s Lethbridge Research Centre.

“One of the things we learned is this stuff will blow,” he said.

After researching the art and science of composting for 20 years, he and other researchers at the research facility have perfected the recipe method.

They have also learned that any organic material can be decomposed into a rich humus-like material.

Most of their work calculates compost’s benefits as a soil amendment.

Read Also

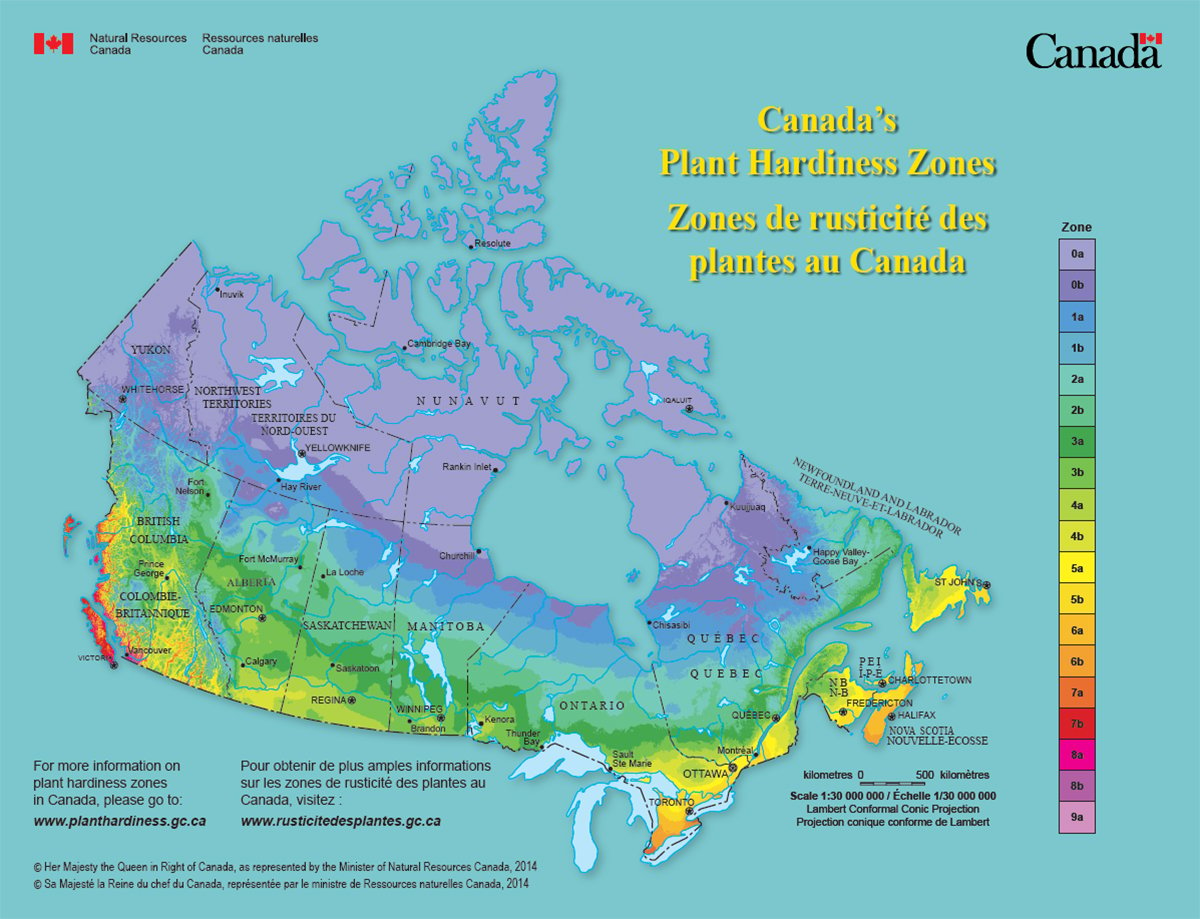

Canada’s plant hardiness zones receive update

The latest update to Canada’s plant hardiness zones and plant hardiness maps was released this summer.

The scientists at Lethbridge were enlisted to find ways to deal with the manure from the millions of animals that are raised each year in the area’s feedlots. The goals were to protect the public and environment from pungent odours and contaminated runoff and to find ways to add value to what many regarded as a waste product.

A local farmer who was experimenting with composted manure lent the centre some of his equipment in 1995 to start the early work.

“There wasn’t a lot of interest in it then. People thought it was too expensive,” said Larney, a specialist in composting and soil reclamation.

Adding manure and compost to soil has been around as long as people have farmed, but in recent years composting has gained some cachet, especially among urban gardeners.

“If you mention manure, they run a mile from you. If you say compost, everybody loves you,” said Larney.

His colleague, soil scientist Jim Miller, agreed.

“When you think about the number of urban people who are composting in their backyards with small portable units and the number of agriculture producers composting, I bet the ratio is a lot higher for urban people,” said Miller.

Prairie soil could benefit from more manure or compost because it adds body to the soil and provides valuable plant nutrients such as carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus.

“When you think of all the land in Alberta, six or seven percent gets manure put on it each year,” Larney said.

“So 93 percent of the cropland doesn’t see manure in a year.

“So you are hoping that seven percent that gets it in one year isn’t the same seven percent that gets it the next year.”

He estimates that five to 10 percent of the manure that generated in southern Alberta is composted.

The benefits of composting are varied. As well, producers need to differentiate between the real thing and stockpiled manure that was allowed to rot.

Composting benefits the environment because manure nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus are converted to more stable forms and are less likely to reach groundwater or move in surface runoff.

Compost can be stored until land application conditions are suitable, and it can be transported more economically than fresh manure, which contains 75 percent water.

“We haven’t sold that message to producers as well as we could have partly because there hasn’t been a lot of work done on the transport economics, ” said Miller.

Farmers will need more acres for spreading if future environmental regulations switch to a phosphorus based measure for land application instead of a nitrogen based measure.

The economics of composting will be attractive if that happens because compost can be hauled farther than raw manure.

Scientists have found that a long windrow piled one to two metres high by three to four metres wide is ideal for large, outdoor composting projects.

Regularly turning the pile for six months, followed by a curing period, should produce a crumbly humus-like material that is free of weed seeds, diseases and odour while retaining valuable plant nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus.

Composting occurs when microbes digest the organic material. The digestion creates heat that can reach temperatures greater than 65 C for an extended period of time. It effectively kills weed seeds, bacteria, parasites and plant diseases.

That level of prolonged heat also makes winter composting feasible because there are fewer nitrogen emissions and the moisture content is retained.

“The losses are a lot lower with over-winter composting. If you compost in July, your evaporation rates can be so high, you can dry it out too fast, and you end up with dried manure rather than finished compost,” said Larney.

“It will cook away all winter long. You can see the steam coming off.”

Compost is not a fertilizer, but it does have long-term benefits for soil. Nutrient levels can be variable.

The best management practice is to test the soil to see what properties are present for plant growth. The application rate should then be calculated when adding compost, manure and commercial fertilizer.

Nutrients can be lost during the composting process, so researchers conducted field trials to measure how much nitrogen and phosphorus is released to plants compared with fresh manure and fertilizer applied to soil.

Manure and compost can also add much-needed carbon to the soil.

However, Miller said the soil aggregates enriched with compost could crumble more easily and be subject to more erosion.

“It still has physical effects on the soil because that carbon is actually improving certain physical properties but not others,” he said.

“The generality that it improves soil physical structure is not necessarily true. Sometimes it does and sometimes it doesn’t.”

Some may question the value of composting when these nutrients are lost.

“A major goal of future composting research should be to maximize nutrient retention (possibly by the use of additives) while minimizing greenhouse gas emissions,” Larney wrote in a research paper.

Contact barbara.duckworth@producer.com