The common fertilizer is now being seen as a potential energy source for electrical generation and boiler use

Right now, about 80 percent of global ammonia production is used for fertilizer.

That figure comes from ThyssenKrupp, a corporation that employs about 100,000 people in 56 countries.

“Ammonia binds air borne nitrogen and makes the most important crop nutrient, nitrogen, available for nitrogen fertilizer production,” ThyssenKrupp says on its website. “As an important base material for fertilizers, ammonia literally helps to put our food on the table.”

That 80 percent figure may soon change because companies and countries are thinking differently about ammonia. The change in perspective can be summed up in five words: ammonia is bigger than agriculture.

Engineers and scientists have realized that ammonia could be used to generate electricity, as a shipping fuel, to power boilers, as a safe way to store hydrogen and dozens of other uses.

“For us, this is a pretty exciting time. It (ammonia) was a fertilizer industry product for the longest time. Now there is all kinds of markets opening up,” said Chris Mancinelli, a chemical engineer with Casale, a Swiss engineering company that designs ammonia and fertilizer plants.

Mancinelli was one of the speakers at the Midwest Farm Energy Conference, held June 15-16 in Morris, Minn.

Ammonia, specifically “green” ammonia, was the main topic of discussion at the first day of the conference.

Most of the ammonia in the world is produced at massive plants that rely on natural gas for the process. But the carbon dioxide emissions from those plants are becoming a problem. To cut emissions, engineering firms like Casale are designing plants that use renewable energy (solar, wind) to produce hydrogen. Then, the green (low-carbon) hydrogen is combined with nitrogen to manufacture ammonia.

One such project is in Queensland, Australia.

“Casale will… design to convert Incitec Pivot Limited’s (IPL) ammonia plant at Gibson Island from natural gas to renewable hydrogen as raw material,” Casale says on its website. “This renewable hydrogen would then be converted into more than 300,000 tonnes of green ammonia for Australian and export markets.”

The potential market for that Australian plant, which is still at the feasibility stage, could be exports to Japan.

In April, Chemical and Engineering News reported that Japan is making a large bet on ammonia as a low carbon source of fuel and energy.

By 2030, Japan plans to triple its annual ammonia consumption to four million tonnes. In the longer run the country wants to convert all coal-fired power plants to ammonia, which would boost consumption to 30 million tonnes per year.

“Ammonia could be Japan’s savior when it comes to thermal power generation,” said Nobuyuki Suzuki, general manager of the Basic Chemicals Division at Mitsubishi Gas Chemical (MGC).

Demand for green ammonia will likely be much, much larger than Japan.

Research firm Markets and Markets has projected that the global market for green ammonia will grow 90 percent annually from 2021 to 2030, reaching US$5.4 billion by the end of the decade.

Part of ammonia’s appeal is it’s loaded with hydrogen, but it’s much easier to store and transport than hydrogen, an extremely light and low-density gas.

Hydrogen is kept in high pressure tanks and the cost is 10 times higher than storing ammonia, said Mike Reese, renewable energy director at the University of Minnesota’s West Central Research and Outreach Centre, in Morris.

“Hydrogen storage is prohibitive,” he said. “That’s why a decade ago, or two decades ago, hydrogen lost favour (for transportation fuel).”

One solution to the hydrogen problem is to produce green ammonia and then move that chemical around the world to where it is needed.

Chemical companies can crack the ammonia to get at the hydrogen, which produces no carbon dioxide when combusted.

“The cracking technology is something that is well established. There’s a catalyst used,” Mancinelli explained. “That hydrogen would be used to replace natural gas fuel in boilers and other uses.”

Another big opportunity for green ammonia could be the shipping industry. It’s very difficult to electrify marine vessels, as there are no battery-charging stations in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

In the last year, trade publications and the mainstream media have written numerous stories on how the shipping industry “is betting big on ammonia” as a new source of fuel.

“Germany’s MAN Energy Solutions and Korean shipbuilder Samsung Heavy Industries are part of an initiative to develop the first ammonia-fueled oil tanker by 2024,” spectrum.ieee reported in 2021.

There may be massive new markets for green ammonia, but there are also challenges. The energy density of ammonia is about half that of diesel fuel and it doesn’t combust as efficiently as diesel.

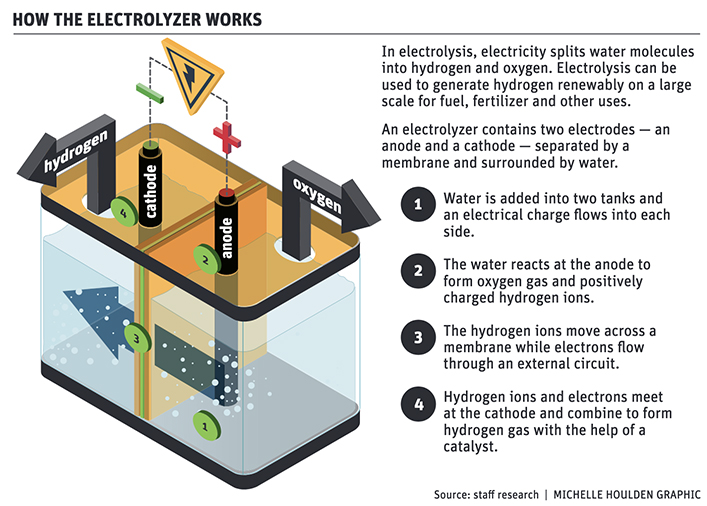

There is also the issue of electrolyzers — devices that are critical to produce green ammonia.

An electrolyzer uses electricity to break the bond between hydrogen and oxygen in water, separating the hydrogen so it can be combined with nitrogen to make ammonia.

“There’s all these people looking at this (green ammonia) but where are these electrolyzers going to come from?” Mancinelli said at the farm energy conference in Morris.

“The capacities for the electrolyzers (to produce hydrogen) is behind some of the ambitions (for) the projects going on.”

Finally, there’s the problem that plagues all industries right now — labour.

In the world of chemical engineering, not enough people have the knowledge and experience to design or operate green ammonia plants, Mancinelli said.

That’s possibly why many companies are focusing on “blue” ammonia, where natural gas is used to make the chemical and carbon dioxide emissions from the process are stored underground.

Still, whether it’s blue or green, corporate and industry interest in ammonia is booming.

“Just in the past one to two years, the level of interest in those technologies has just exploded,” Mancinelli said. “Especially on the green side, going from almost nothing to… we’re getting calls weekly from people who are looking at big projects.”