Like most farmers on the Prairies, the 2021 growing season was a struggle for Stuart McMillan, who manages Legend Organic Farms near Kamsack, Sask.

Many crops on the 3,500-acre farm couldn’t handle the drought and extreme heat when many days reached 30-35 C, and yields were well below normal.

“Our oats just took a kicking. They didn’t seem to handle the really high heat, which coincided with flowering,” said McMillan. “I think our (yields) were around 18-19 bushels this year.”

Other crops were more successful, especially the flax.

In a typical year, McMillan shoots for flax yields of 15-18 bushels per acre. The 2021 crop nearly reached that target.

“Our main flax field did go… 15-16 bushels an acre,” he said.

Across Saskatchewan, some organic crops withstood the severe growing conditions of last summer, possibly because there was more organic matter in the soil and the field was able to retain more moisture. Research by the Rodale Institute in Pennsylvania has shown that organic farming systems are more resilient to drought, McMillan said.

“(Because) they (farmers) were working to build up their soil organic matter, through their use of cover crops and green manure plow-downs,” he said. “If an organic producer has designed their system … that has a real, heavy focus on perennial cropping and green manures that are going to be adding that carbon back into the soil, it’s very likely that those systems can be more resilient.”

But organic farmers rely on tillage to control weeds. Tillage dries out the soil and likely caused yield losses in 2021.

“Any amount of tillage done (last year) seemed to have burnt off whatever soil moisture there was,” McMillan said.

Across the province, organic crop yields from 2021 will be significantly below the long-term average. But provincial yield data won’t be available until March, Saskatchewan Crop Insurance Corp. said in an email.

Farmers have told SaskOrganics that yields were disappointing, but there were some positives.

“On an average, organic production held its own against the conventional model,” said Garry Johnson, SaskOrganics president and a producer from Swift Current. “Quality… in the organic side was extremely high.”

On his farm, Johnson had success with a multi-species crop where he grew oats, peas and buckwheat in combination.

“It was far beyond anything we had (for yield),” he said. “It was far better than anything else. …. I think there is something to this. It covered the ground extremely well…. It was flourishing until it ran into the extreme heat later on in the season.”

Practices like multi-cropping, including perennials in the rotation and reducing tillage, could make organic farms more resilient to drought. But those practices only make a difference if farmers use them.

“I don’t really think that (those practices) are necessarily the norm for all of Western Canada’s organic acres,” McMillan said.

Some organic farms could be more tolerant of drought, but the yield gap between organic and conventional production remains large in Saskatchewan.

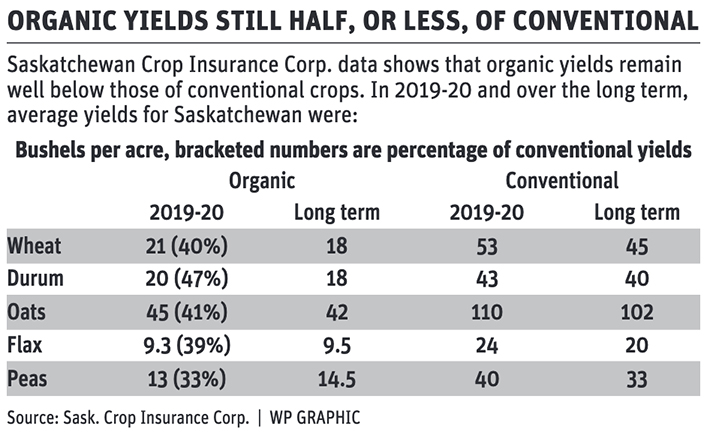

SCIC data from 2019-20 shows that organic yields were about 40 percent of conventional:

- The average yield for organic spring wheat was 21 bushels, 40 percent of the 53-bu. average for conventional.

- Organic flax was 9.3 bu., 39 percent of the 24-bu. average for conventional.

- Organic oats were 45 bu., 41 percent of the 100-bu. average for conventional.

SCIC, in an email, said organic yields are “significantly higher” when a crop is planted following green manure, where clover, alfalfa, legumes, radish and other species are seeded to improve soil fertility in a particular field.

“Twenty-five percent (more yield) is definitely achievable after green manure or clovering,” Johnson said. “It’s very significantly higher.”

A movement within Canada’s organic sector is encouraging farmers to focus on soil fertility and improve per acre production. If an organic farm is well managed, yields should be much higher than 40 to 50 percent of conventional.

“Seventy percent of conventional on cereals. Soybeans (should be) higher. Forages are higher,” said Martin Entz, a University of Manitoba plant science professor who specializes in organic cropping systems, in the winter of 2020.

“Seventy percent of conventional. That’s a good organic farm.”