SASKATOON – Farmers in Manitoba had better get used to dealing with fusarium, because it’s not about to go away.

“It is going to be here, I guess, for eternity,” said Randy Clear, a crop disease expert at the Canadian Grain Commission.

Experience has shown that once the fungal organism that causes fusarium head blight becomes established in an area, it becomes a chronic problem. While its impact each year depends largely on the weather, no soil treatment or other measures will get rid of it.

Read Also

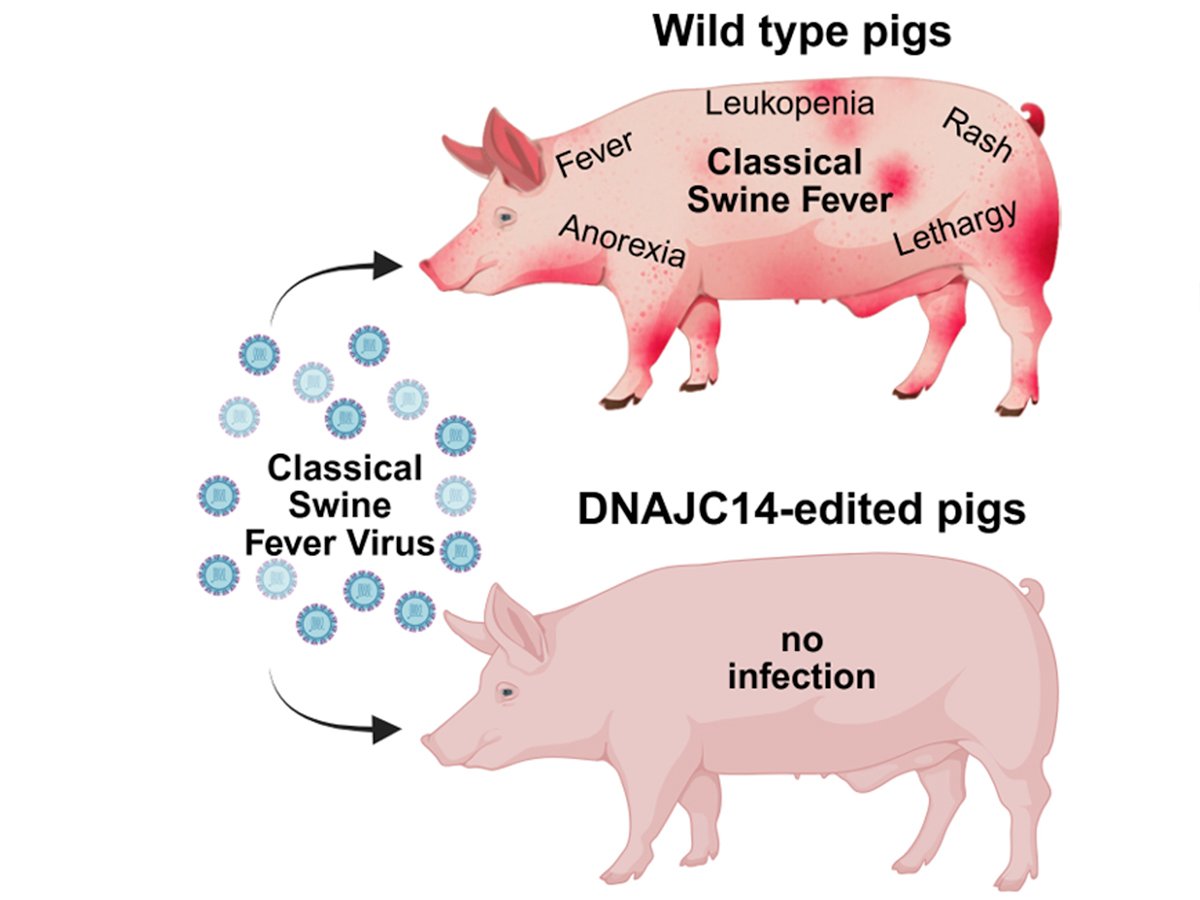

Gene edited pig resistant to classical swine fever

British scientists have discovered a gene edit that could provide resistance to classical swine fever in pigs and Bovine Viral Diarrhea in cattle

“There doesn’t appear to be any economical way of controlling it,” said Clear, adding the disease has driven the production of certain varieties and classes of cereal grains out of some areas of the United States.

Last week officials of the grain commission, the Canadian Wheat Board and the Manitoba and Saskatchewan departments of agriculture met in Winnipeg to review strategies for dealing with this year’s outbreak.

Grain commission head Milt Wakefield said the goal is to minimize the impact on farmers while at the same time protecting Canada’s reputation for quality control.

“We have dealt with FHB (fusarium) before and buyers of Canadian grain can be confident this outbreak will have no impact on the quality of their purchases,” he said.

Canadian Wheat Board information officer Rhea Yates said some customers will accept a certain level of fusarium in wheat shipments while others have zero tolerance.

The grain commission allows a prescribed amount of fusarium, measured as percentage of total weight. Farmers who deliver grain in excess of that level will have their payment reduced accordingly.

Losses up to 50 percent

Farmers in southern Manitoba have been warned to expect a 10 to 20 percent reduction in wheat yields because of fusarium, with losses in some fields exceeding 50 percent. It will likely be the worst outbreak since 1993.

The disease is most intense in the Red River Valley, but every crop district in Manitoba has detectable levels. It has also been detected in southeastern Saskatchewan, but is not yet considered a serious problem.

“We haven’t seen anything in Saskatchewan to date that warrants immediate concern,” said Clear. “But the idea is that if it’s approaching into Saskatchewan, what is going to be the situation there several years from now? We’re not sure.”

The disease spreads by wind and likely through infected seed transmission. It causes wheat or barley kernels to shrivel. Under damp weather conditions it produces a mycotoxin making it unsuitable for consumption by humans or livestock.

Clear said the grain commission first noticed fusarium in Manitoba in 1984. While it was held down by several dry years in the 1980s, since then it has been spreading every year.

Exactly why it has become so common remains somewhat of a mystery, although it could be related to cropping practices or the use of certain susceptible varieties. Durum is particularly susceptible, as is Roblin hard red spring wheat.