Avena Foods works with oat growers who follow a special system to help prevent wheat contamination

A specialty oat marketer in Regina is eager to add the words “gluten free” to its packaging.

Avena Foods already markets its cereal, pancake, muffin and cookie mixes as “wheat free,” but proposed changes from Health Canada would allow the farmer-owned company to take advantage of the consumer buzz word.

The move allows the company to further target a segment of shoppers who, for one reason or another, want to avoid eating the grain protein.

“We would immediately adopt the Health Canada opportunity,” Avena chief executive officer Rob Stephen said about the proposed regulations announced in November.

Read Also

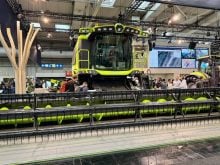

Agritechnica Day 3: Hybrid drive for a combine, data standards keep up to tech change and tractors of the year

Agritechnica 2025 Day 3: Hybrid drive for a combine, data standards keep up to tech change and tractors of the year.

“We think it’s great for the consumer and we think it really adds clarity and it’s something that we’ve been working hard at for six or seven years.”

Oats shouldn’t cause medical problem for people with gluten issues, but consumer products can be contaminated with crops that contain gluten, either in the field, a mill or a processing facility.

Specialty producers take extra measures to avoid that contamination. In Avena’s case, the company works with more than 50 growers in Saskatchewan and Manitoba under a specialized production system that keeps wheat out of their rotation for at least three years.

Avena buys common varieties such Dancer or Orrin, which are chosen for their milling qualities. They are all grown conventionally.

However, Stephen said growers use an isolation strip, clean equipment and pedigreed seed to help keep out wheat volunteers.

Oats are tested for gluten content when entering the facility and again in a laboratory at the company’s Regina headquarters, where it em-ploys 45 people.

Health Canada’s proposed changes would allow oat products that contain less than 20 parts per million of gluten from wheat, rye and barley to claim gluten-free status.

The new regulations aren’t in place yet, and Health Canada is taking comments on the proposals until Jan. 29.

Stephen said Avena, which carries certification from a gluten-free organization, strives for 10 parts per million.

The company markets its Only Oats brand in Canada and supplies ingredients in other countries such as the United States, which has a higher standard for gluten content.

An American study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2004 found that gluten content in most rolled and steel-cut oats on store shelves was higher than the 20 ppm threshold, with amounts varying from 23 to 1,807.

“Unless you’re a specialized processor of gluten-free oats, you can’t really make that assurance,” Stephen said.

“You need the audit verification. You need the lab. You need the dedicated facility. You need the specialized growers who know how to do it.”

Avena’s origins in the late 2000s predate much of the hype and debate around gluten-free products, which were spurred by controversial books such as Wheat Belly and trendy diets that introduced the phrase into the popular vernacular.

However, Health Canada said in 2007 that most people with Celiac Disease could tolerate eating some uncontaminated oat products. It further updated its recommendations in 2014 to say that celiacs need not limit their consumption of specially produced oats.

People with celiac disease have a diagnosed sensitivity to gluten and make up about one percent of the population.

Evidence of the gluten-free sector’s growth is easy to find: whole sections of urban groceries are now dedicated to the products.

In addition to Avena, the Canadian Celiac Association lists three other brands of specialty oats marketed to celiacs in Canada: Cream Hill Estates, Glutenfreeda and Bob’s Red Mill Oats.

“The celiac patients have driven the creation of a lot of this marketplace, but there’s also a lot of folks who are gluten sensitive, who have a reaction when they consume gluten, and people are making lifestyle choices around avoiding gluten as well,” said Stephen.

A mill line expansion announced in 2014 expanded the company’s production capacity by 50 percent.

Stephen said he sees a “layered” market for these products.

As much as 30 percent of shoppers are making gluten-free purchases, he said.

Of that group, a small minority are celiacs, but the segment grows with their families, who are also adopting the diet, and others who may have some symptoms of gluten sensitivity.

As much as half of gluten conscious shoppers are making the purchase as an elective lifestyle choice, he added.

“That’s kind of the wave that we’ve been riding. It’s a long-term, sustainable health-care trend,” he said.

“It’s not a quick thing. We’ve been in it for six or seven years and continuing to grow. The company has been growing at a compounded rate of over 60 percent over that time period.”