OLDS, Alta. – The Maine Anjou breed is the heart and soul of Matthew and Margie Campbell’s ranch west of Olds.

They are so confident in the merits of this breed that they volunteer every spare minute to promoting the cattle at shows and sales as well as talking up the breed to commercial producers looking for bulls or replacement females.

“A Maine cross on an Angus cow is such a phenomenal cross, they fit together like a hand in a glove as far as I’m concerned,” said Matthew, who is a second generation Maine Anjou breeder and a director with the Canadian association.

Read Also

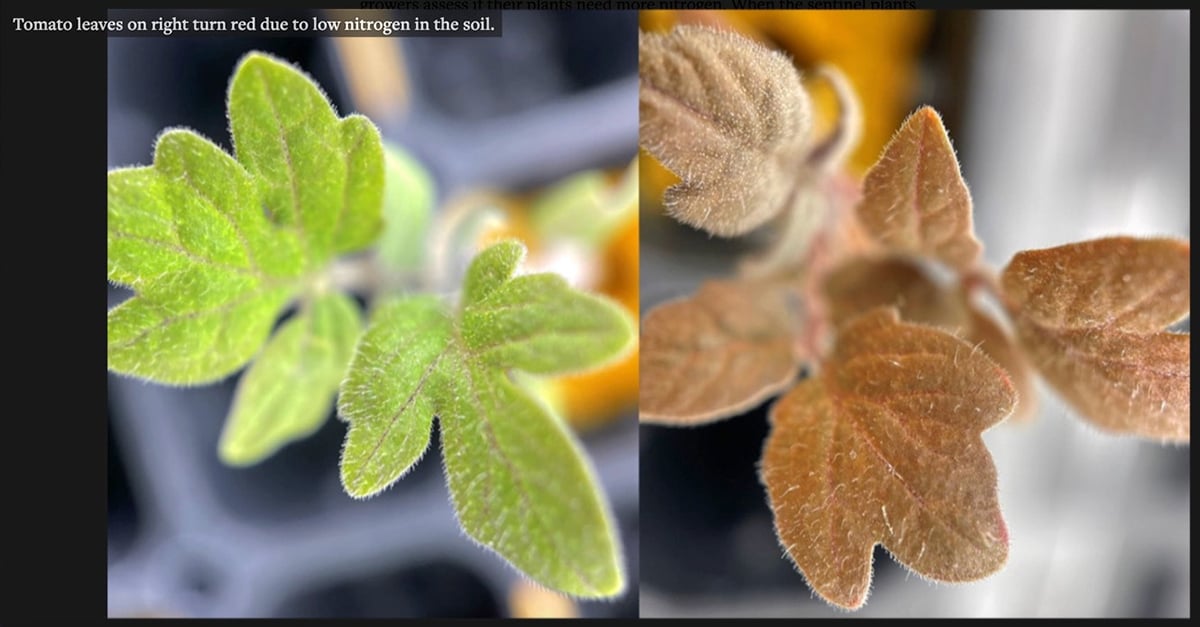

American researchers design a tomato plant that talks

Two students at Cornell University have devised a faster way to detect if garden plants and agricultural crops have a sufficient supply of nitrogen.

Margie has been the volunteer secretary-treasurer for the Alberta Maine Anjou Association for the last nine years developing promotional material, pulling together shows and sponsors, as well as publishing a regular newsletter and designing cattle web pages.

The Anchor C Cattle Co. pastures contain 150 crossbred, purebred and full-blood cattle. They raise solid red and black purebreds, as well as the traditional red and white full bloods that trace their ancestry directly to the original imports from France.

“We’re tending to go for solids,” Margie said.

“That’s what the market wants, is the solid red or the solid black.”

The cattle have changed considerably since the first imports arrived in the continental rush from Europe more than 30 years ago.

Matthew’s father John Campbell of Millarville, Alta., was among the first to use Maine Anjou cattle after they were imported from France in 1971-72.

“When the continental breeds came out, Dad tried every breed that came along and he settled on Maines,” he said.

John had a small feedlot and appreciated the breed’s gain, feed conversion and high red meat yield.

The big red and white cattle were retrofitted for Canadian conditions. Used for milk and meat in France, Canadians turned them into a moderate- sized animal to be used exclusively as beef cattle.

Colour started to change to solid black in the early 1990s. This matched the trend in the United States, where producers could be paid a premium for cattle with black hides.

The Campbells feel their breed is a well kept secret with good quality meat and docile cows that cross well with other breeds.

Matthew also runs a custom fencing business so the Campbells want easy-to-manage cattle when he is away.

They also recognize that what works for them may not fit in other programs and if a potential buyer has specific requests for colour, horns, polled, purebred or full blood, they help find someone who can meet the specifications.

“We are targeting the commercial cattlemen rather than seedstock producers in our marketing program,” Matthew said.

When the Campbells select females and bulls, they prefer to ignore pedigrees and judge the animal on individual merit.

“At branding time we have a deal. If one of us doesn’t like it, it doesn’t stay a bull,” Matthew said.

“The best place to buy bulls is from the guy with the sharpest knife.”

While they sell purebred bulls by private treaty, steers destined for the feedlot pay the bills on this ranch. A sideline business has been selling prospects for 4-H and steer shows. This was a good market to break into because American steer shows can earn people thousands of dollars in prize money. Matthew said the U.S. customers are discriminating buyers.

“We had Americans come up and actually buy females they figured would give them show steers and take them back.”

Like other purebred producers, the Campbells are anxious to return to the U.S. market with breeding bulls and heifers.

“As a breed we need to get down there and rebuild the confidence in what Canadian cattle can do,” Margie said.

Promoting cattle takes many forms.

The family, including their son Austin, shows cattle around the province. Austin has been showing since he was four years old and is a member of the newly formed provincial junior Maine Anjou association, which held its first show in Red Deer last summer.

The national show to mark 35 years of the breed in Canada was held at Farmfair International in Edmonton last fall with 185 head.

International interest was strong and the Campbells met many people who had learned about the breed from the internet.

They consider websites and on-line auctions the wave of the future because everyone who visits a site is a potential customer.

“Technology will make the beef genetics worth more and offers a wider market base,” Matthew said.

They believe so strongly in this that they bought a bull on-line while visiting Disneyland this year.

“The internet has been a good marketing tool for us personally,” he said.

Almost all Canadian purebred breed associations suffered when many countries banned Canadian cattle after BSE.

The Canadian Maine Anjou Association’s membership has dropped to 110 active members from 400.

Now the Campbells are confident in a comeback, partly because of increased use in the United States.

“With the potential of the border opening and the breeding cattle portion opening, we are going to do nothing but get bigger,” Margie said.