Two years ago, voters in northern Alberta had to decide whether they wanted Tom Jackson to represent them on the Canadian Wheat Board’s board of directors.

Now, voters hundreds of kilometres away have to ponder the same question.

Jackson hangs his hat at Ardrossan, Alta., just west of Edmonton, within the boundaries of wheat board electoral District 1.

That’s the district where the 42-year-old grain farmer ran in 1998, garnering just under 44 percent of the votes and losing to Art Macklin on the second ballot.

Read Also

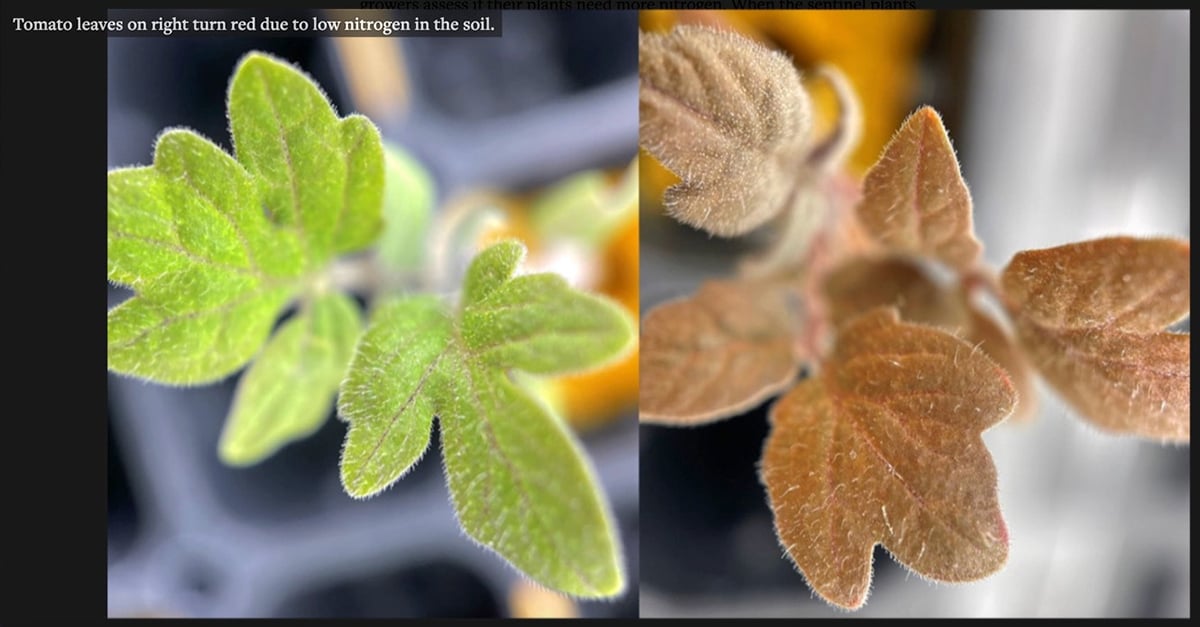

American researchers design a tomato plant that talks

Two students at Cornell University have devised a faster way to detect if garden plants and agricultural crops have a sufficient supply of nitrogen.

In this year’s wheat board election, he’s running in District 4, which begins 90 kilometres to the east of Ardrossan and runs across the Saskat-chewan border to near Saskatoon.

Jackson is within the rules because he is involved in a grain farm that operates in District 4. He makes no apologies for deciding to run in a different district than last time.

He says his farm at Ardrossan has more in common with District 4, in terms of geography, environment and cropping patterns, than it does with the Peace River area, which makes up a large part of District 1.

“It’s a real tough one, because we live right in the corner of four districts,” he said, referring to districts 1, 3, 4, and 5.

Under the rules he could run in any one of them, along with districts 2 or 6.

Jackson, who gained a high public profile a few years ago when he went on a hunger strike to protest wheat board marketing rules, has an interest in three separate farms: at his home at Ardrossan, in the Jarvie area north of Edmonton, both in District 1, and at Killam, Alta., which is in District 4.

He doesn’t think living outside the district would present him with problems in representing the views and interests of his constituents if he was elected.

“It’s simply a matter of are you willing to do the research and find out what kind of things the folks are encountering, and are you willing to represent their needs and aspirations,” he said.

Ken Ritter, running for re-election in District 4, said several farmers have privately raised with him the fact that Jackson doesn’t live in the district, but he said that as far as he’s concerned, it’s not an issue.

“If he qualifies in the eyes of the election co-ordinator, that’s good enough for me.”

He said there are more important issues to talk about in the campaign.

The rules state that a candidate can run in the district in which he or she grows grain or in a bordering district. In some cases, that would allow a candidate to choose from among six districts. The candidate’s 25 nominators must be eligible to vote in the district in which the candidate runs.

Earl Hawthorne, also running in District 4, said he didn’t know where Jackson lives. Residency could be an issue depending on the circumstances, he said, but added he didn’t know enough about Jackson’s situation to comment.

Jackson said he can foresee the day when he has to move from Ardrossan, estimating he loses 100 acres of land annually to housing or industrial development from Edmonton’s urban sprawl. When that day comes, he may increase his operation at Killam.

Meanwhile, one election lobby group has complained about the rules that determine the district in which individual voters cast their ballots.

CARE (an acronym standing for choice, accountability, responsibility and efficiency), which is promoting the election of candidates who support a dual market, says farmers should vote in the district in which they live and farm.

Under the rules, voters are assigned to districts based on the delivery point where they took out their permit books, which may not be the same district where they live or farm.

However, election co-ordinator Peter Eckersley said a producer has the right to vote in the district in which he or she grows grain. A farmer can change voting districts only once.