ST. ALBERT, Alta. – The largest land donation ever received by a Canadian university may invigorate what had seemed a bleak future for on-farm research at the University of Alberta.

Agriculture dean John Kennelly, who helped bring the university and the family together, said the donation is significant.

“It’s big. We’d love to mention the number because it’s really, really big.”

The Bocock family has made a multimillion-dollar donation of prime farmland on the edge of Edmonton to the university for agriculture and environmental research.

Read Also

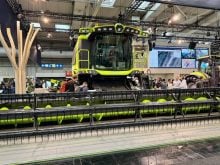

Agritechnica Day 3: Hybrid drive for a combine, data standards keep up to tech change and tractors of the year

Agritechnica 2025 Day 3: Hybrid drive for a combine, data standards keep up to tech change and tractors of the year.

Kennelly said the future of on-farm research at the university was uncertain as it faced closure of the Ellerslie Research Station by 2011. The university had little hope that it could replace the research farm with a new facility that would be an easy driving distance for university staff and students.

Enter the Bocock family.

Selling the 777 acres of land to the university for a fraction of its appraised value enabled them to ensure the land, which has been in the family since 1921, would remain in agricultural production.

“To know that our land will continue to be used for food production and then as a bonus for research, that was important to us,” John Bocock said during a June 4 ceremony in a billowing white tent at the edge of a barley field already divided into research plots.

Members of the Bocock family – Bill and Phyllis, John and Jenny and their daughter Rachel – had struggled with a decision about what to do with the land as they watched the city creep closer to their dairy farm.

The family had talked about giving the land to aboriginal people. They considered placing it in a conservation trust, but there was no exotic burr, bog or bird to protect, just good farmland slowly being swallowed by urban development.

“Our family does not agree on all things. Those who work and live with us know that. But we do agree that farmland can and must be preserved,” Phyllis said.

“We believe that the University of Alberta will honour the commitment we made.”

Donating the land to the university for agriculture research seemed the perfect solution, especially considering the university was about to lose its present research farm to urban development on the south side of Edmonton.

“This is truly a transformational moment in the history of the University of Alberta,” said university president Indira Samarasekera.

“It gives us the means to secure agricultural and environmental research in Alberta for years to come.”

The Bococks’ donation is the largest gift of land for research ever made to a Canadian university. No one would say how much the university paid for the land, but Phyllis said they got “a heck of a deal.”

Kennelly said he developed a strong bond with the Bocock family as negotiations progressed, even during the difficulties of the final round.

“What kept us going was we absolutely trusted each other. It was always a very open dialogue.”

Alberta advanced education minister Doug Horner said he wasn’t optimistic the university would be able to find a suitable facility.

“The kind of problem you folks have solved is unbelievable,” Horner told the Bococks.

“I am absolutely in awe of the selflessness of this family.”

In recognition of the gift, the university has established the Bocock Chair in Agriculture and Environment. It will study the interactions between agriculture and the environment using interdisciplinary approaches to seek a balance between sustainable food and bioproduct production, economic viability and environmental health.

The donation isn’t without strings. The family has requested research on the farm look at alternatives to traditional agriculture methods.

“Despite dry years and hail, for as far back as there are records, this farmland has never failed to produce. The worst threat has been air pollution from industry. Pollution has affected the health of family members, employees, livestock and vegetation,” said Bill, who has fought for years to reduce the amount of flaring from surrounding gas wells.

“It is our hope that some of the research done here will provide alternatives to the dependency of North American agriculture on petroleum products. We have confidence the university will be good stewards of this land.”

Reint Boelman wasn’t surprised by the family’s generosity. Shortly after he emigrated from Holland, the Bocock family welcomed him into their family, where he worked for a year. The Bococks gave him low interest loans to start his own dairy farm at Westlock, Alta.

“They were my employers, but they were my best friends through thick and thin.”

As soon as the ceremonies were finished, research associate Keith Topinka returned to the fields to continue his work on land that he said is ideal for research: flat, low salinity, 11 percent organic matter and almost weed free.

“It’s a wonderful site,” he said. “The farmers have obviously taken good care of this land.”

The Bococks have kept two quarters of land: the home quarter where the two families live and an adjoining one.