Victim’s case has commonalities with subtypes infecting poultry birds and dairy cows across North America

The highly pathogenic avian influenza that put a British Columbia teenager in critical condition appears to be the same subtype that has infected poultry farms in Western Canada and dairy herds in the U.S.

The Public Health Agency of Canada National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg verified Nov. 13 that the teen’s illness was caused by the influenza A H5N1 virus.

As of Nov. 15, 34 farm sites in Canada had a bird flu outbreak. Investigators confirmed the virus genotype in the B.C. cases as influenza A H5N1, clade 2.3.4.4b, genotype D1.1.

Read Also

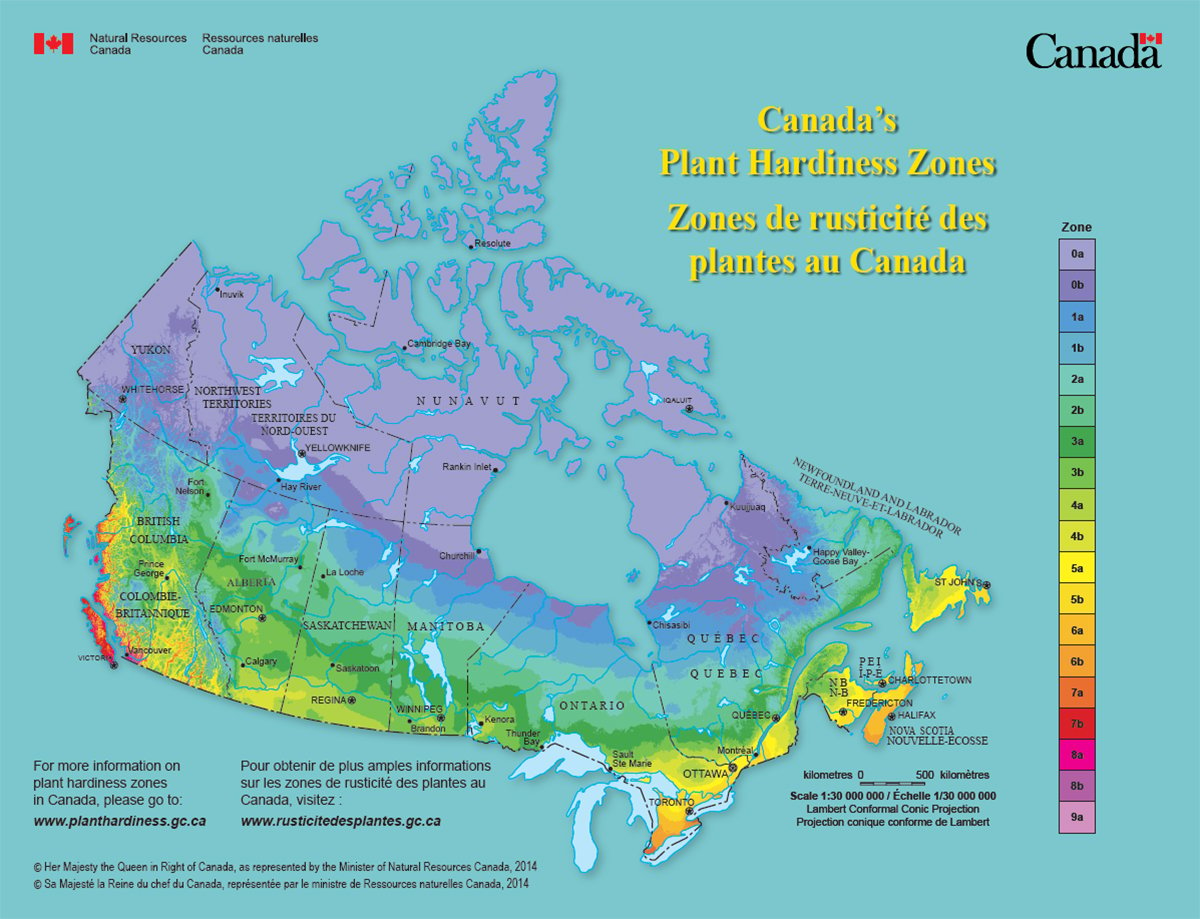

Canada’s plant hardiness zones receive update

The latest update to Canada’s plant hardiness zones and plant hardiness maps was released this summer.

Most cases are in B.C., with hot spots around Abbotsford and Chilliwack. Three Alberta operations, including a commercial poultry farm and a small-scale flock, have also fallen victim, as has a commercial poultry operation in Saskatchewan.

The teenager’s illness is the first domestically acquired human case of H5N1 avian influenza in Canadian history but the Public Health Agency says risk is low to the general public. There is higher risk for those who have had unprotected exposure to infected animals.

It’s not yet known how the teenager contracted the virus. They reportedly had no contact with farm animals but had been exposed to dogs and cats, both of which have been known to contract avian flu.

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency says the virus is not a food safety concern. Shayan Sharif, a professor with the University of Guelph who has been tracking viruses in this clade for several years, said the likelihood of contracting the virus by eating poultry is extremely low and almost non-existent.

Avian flu is not a food-borne illness. Although dairy cattle have been found to harbour the virus with no clinical signs, a flu breakout in a poultry flock is immediate and obvious, Sharif said.

“You see a drop in production, a reduction in water consumption and feed consumption and then you have your chickens coughing and sneezing and panting. And then, over very short periods of time, you see high mortality.”

The CFIA asks anyone who discovers symptoms of avian flu to call the agency immediately. It will then take samples and determine whether the symptoms are the result of bird flu. If positive, the flock will be destroyed.

”So as a result of that, there is no chance of this virus entering the human food supply chain,” said Sharif.

If any trace of bird flu remains in meat, it is destroyed by cooking.

“Even temperatures as low as 60 to 70 degrees (C) can deactivate the virus.”

Sharif is also confident the patient did not catch the virus from another person.

“To my knowledge, there’s been no human-to-human transmission. There have been some suspected cases of human-to-human transmission, but it’s never been proven.”

Since the start of North America’s outbreaks in late 2021, the CFIA says just under 11.9 million domestic birds have been affected, either by infection or culls.

Another genotype of the same virus group has infected 450 U.S. dairy cattle herds in 15 states since March. The virus appears to primarily be a production disease targeting lactating dairy cows. Canada has had no reported cases in dairy cattle and no evidence of bird flu in milk.

Sharif has been tracking the genotype now attacking poultry since its arrival in Canada. The proverbial canary in a coalmine, he said, was a domestic dog that died from eating an infected goose or duck. Migratory birds are considered carriers of the virus.

“Probably we were just looking at the tip of the iceberg because it takes a lot of time and effort to test a dog that might have all of a sudden died for some unknown reasons. So there might have been more,” he said.

The good news is that the genotype is highly predictable in its travel patterns.

“Since March of 2022 it’s been crisscrossing the country and we usually see surges of this virus in the fall and then in springtime, coinciding with migration of birds.

“And it goes west, it goes east, then it comes back again. So it’s a bit of a messy situation in some respects but it’s rather predictable because now we know that this virus is coming back, for example, in the fall and then another episode is going to happen in springtime.”

Sharif described the appearance of an HPAI infection in a poultry flock.

“This virus can kill chickens within 48 to 72 hours. So the farmer goes into the barn, they’re happy and healthy. The next morning they would see major reduction in their activities. And then, within a matter of few hours, they could be dead.

“It’s not one of those diseases that would lurk around for too long because it hits the chicken farm or turkey farm, kills them and then that’s pretty much it. Only a very few (birds) can survive.”

Canada needs a vaccination strategy for poultry similar to what other countries are developing, said Sharif. France has been mass-vaccinating duck farms since last year.

“That’s one critical element that we need to think about. Are we at the stage that we will move towards vaccination of our poultry? And if that’s the case, then is that going to be for emergency vaccination or is it going to be some sort of a preventive vaccination?”