LLOYDMINSTER – Each morning Glenda Elkow loads buckets of oats onto the back of her quad and makes her rounds out to the elk.

The chair of the Alberta Elk Commission pours the oats into a trough in each pasture, scratches the head of a quiet bull, marks down which bulls have lost their buttons and counts every animal.

The daily head count is part of the elk association’s traceability program to monitor chronic wasting disease, which could have been the death sentence for the elk industry.

Read Also

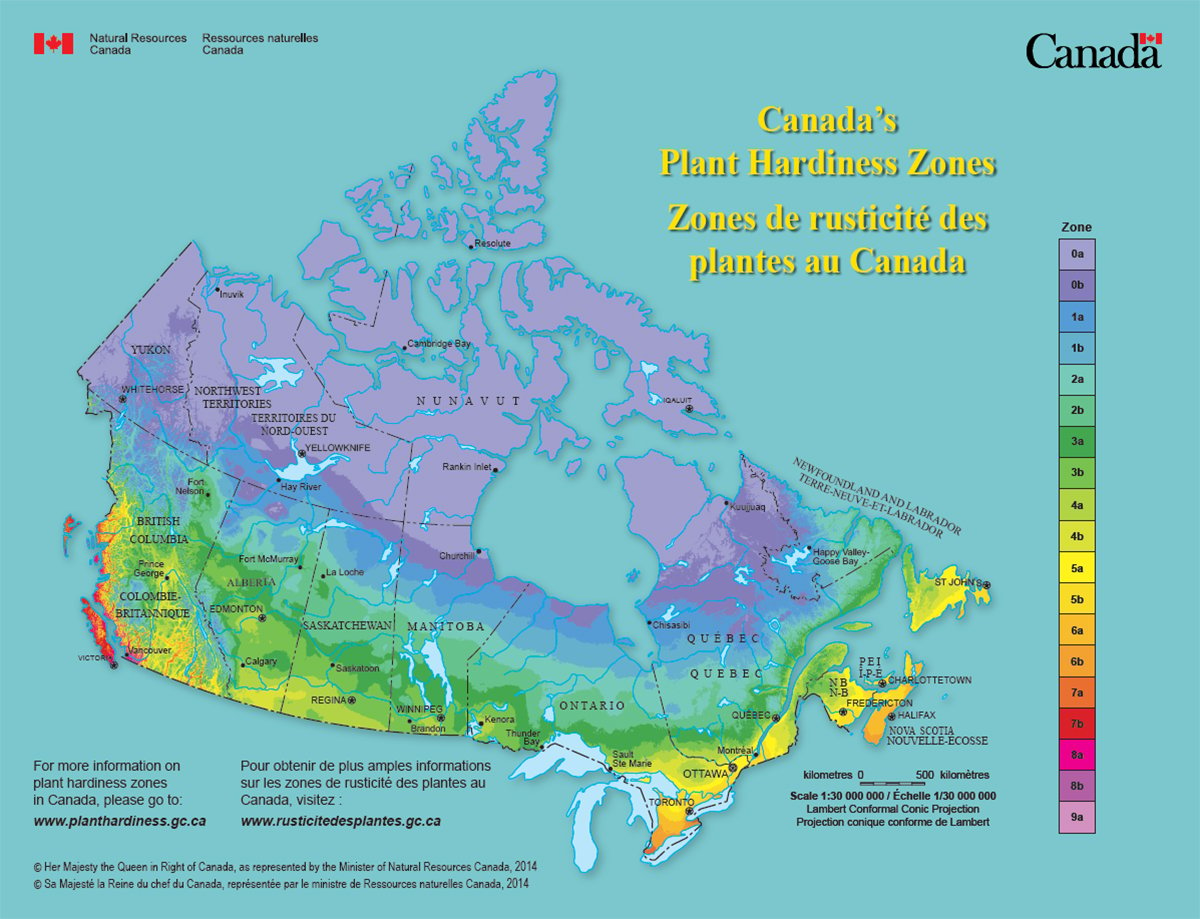

Canada’s plant hardiness zones receive update

The latest update to Canada’s plant hardiness zones and plant hardiness maps was released this summer.

Instead, CWD has dealt the industry more of a continual beating than a knock-out blow.

“Our biggest challenge has been CWD,” said Elkow.

In 1996, Alberta elk and deer ranchers implemented a surveillance program to test for the neurological disease found in cervid animals: elk, moose, white-tailed deer and mule deer.

The program was made mandatory in 2002 after a farmed elk in Alberta tested positive for the disease.

As part of mandatory testing, the head of every elk killed for slaughter or that dies on the farm must be submitted for testing to reassure consumers, governments and overseas customers that farmed elk are free of CWD.

No other farmed elk have ever tested positive for CWD in Alberta.

Having a traceability program in place for almost 15 years hasn’t stopped governments from closing markets or putting up temporary barriers blocking sales.

In 2000, South Korea, Canada’s largest and best customer for the lucrative elk velvet antler industry, was closed after CWD was discovered in an elk exported from Canada in the mid 1990s. The border has never reopened.

In 2001, the Saskatchewan government closed the border to Alberta elk for 18 months after the discovery of CWD in farmed Alberta elk.

In 2002, the Alberta government said hunt farms would not be allowed in the province.

In 2003, when BSE was discovered in a northern Alberta cow, the United States closed its borders to Canadian beef and elk, temporarily eliminating the lucrative trophy bull and breeding animal market.

Since then, the U.S. has banned elk from a 40 kilometre zone around positive CWD cases, which has blocked some elk producers from shipping to the U.S.

The combination of closed borders and government bureaucracy has driven down prices for Canadian elk products.

Producers earn about half the price for elk velvet antler as farmers in New Zealand, said Elkow.

The five-year average for world velvet prices is about $56 a pound. With each elk producing about 30 lb. of velvet, that translates to about $1,500 an animal.

Last year, Alberta producers re-ceived about $16 a lb., or about $480 an animal.

Producers estimate they need at least $26 to $30 a lb. to pay for feed, upkeep of the animals and to make a living.

They’re hoping rumours of lower New Zealand velvet supply will boost prices closer to that $30 a lb. mark. It’s still a far cry from the $120 a lb. producers received in the industry’s glory days, but it would mean prices are heading in the right direction, Elkow said.

Lower prices and decisions by local and foreign governments have frustrated some producers and forced others to leave the industry.

“We enjoy the animals. The frustration is partly because of market access issues and legislation overburden,” she said.

In Alberta, the agriculture department and sustainable resource development, which also looks after the province’s wild deer and elk, govern the farmed elk industry.

“We should be solely governed by agriculture. We are not raising wildlife,” said Elkow.

And if there is a bright side to the closed foreign borders, it has forced the industry to develop local meat and antler markets.

“It led to producers getting together and forming a co-op and doing their own marketing. We now have a burgeoning meat industry. But that has taken a lot of time, energy and resources.”

Elkow said she hopes one day hunt farms will be allowed in Alberta. She said it’s frustrating to watch the bulls leave for Saskatchewan or the United States.

“Politicians have to come to understand this is an agricultural commodity we’re raising that has unique markets.”

A meat bull could fetch $500 to $900. The lowest price paid for a hunt bull would be $1,500, but $3,500 isn’t unusual and can go as high as $50,000.

Despite the trials, Elkow said she and her husband, Terry, are committed to the elk business.

They have bought another farm about 30 kilometres west of their farm on the edge of Lloydminster and this summer will begin the process of fencing and moving their animals to the new farm. They then plan an elk breeding expansion program.

“We like what we do and we know there is potential and the opportunity is huge,” she said.