STRATHMORE, Alta. – Talk radio is piped into the turkey barn at Country Lane Farms.

The chatter is not for the edification of the turkeys, but to keep the coyotes away.

That is not the only innovation at this poultry farm owned by Jerry and Nancy Kamphuis, who live near Strathmore, 25 kilometres east of Calgary.

Ten years ago they decided to raise their chickens without antibiotics and were among the first to feed the birds a whole wheat ration. They also switched from selling to the local co-operative to marketing roasting chickens privately. Their customer base has grown to about 4,000 people from Canmore to Calgary.

Read Also

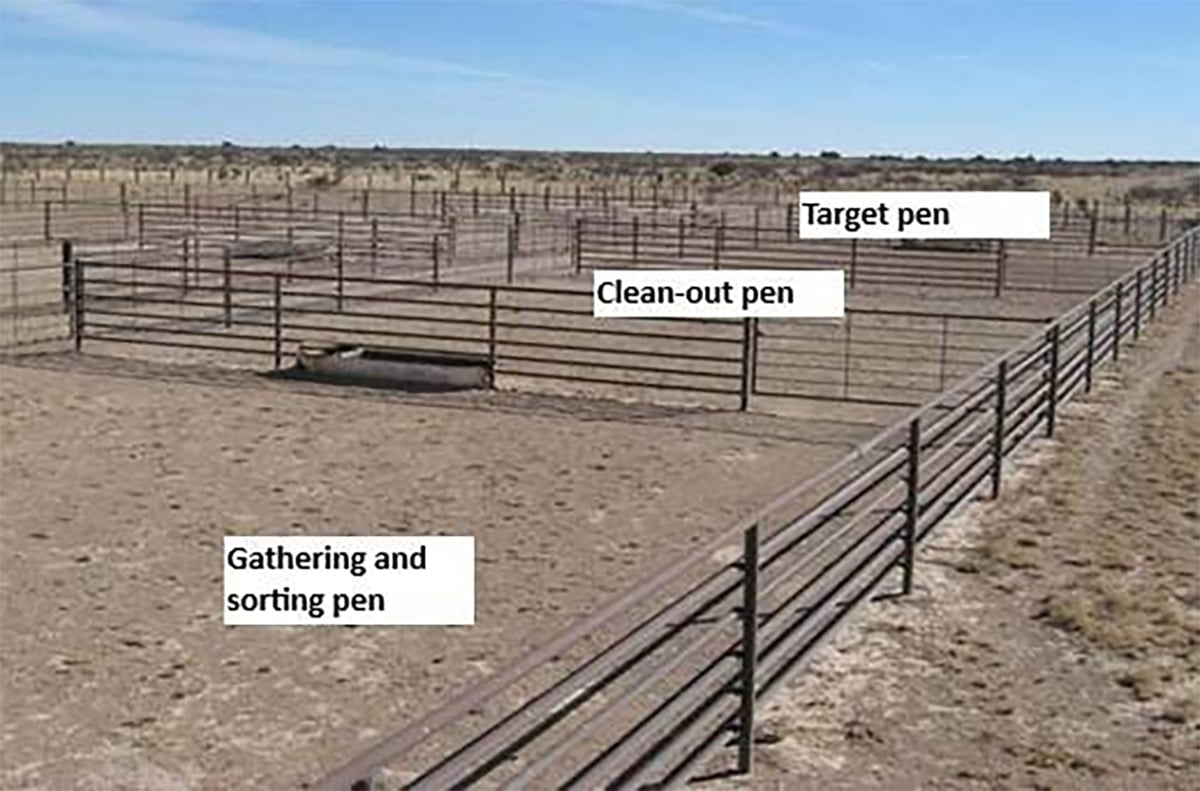

Teamwork and well-designed handling systems part of safely working cattle

When moving cattle, the safety of handlers, their team and their animals all boils down to three things: the cattle, the handling system and the behaviour of the team.

They raise about 4,000 birds at a time in three different growth stages so they can provide chicken year round. In response to customer demand, they added 300 turkeys this year.

While many commercial producers grow smaller chickens to satisfy fast food restaurants, this couple found many people wanted a bigger bird for family meals. They sell their birds when they reach about three kilograms. Some broilers are also available.

“What we’re doing here is focusing more on what the consumer wants,” said Kamphuis.

Their research also told them people want fewer antibiotics used.

Poultry producers may use antibiotics in raising chickens as long as there is a five day withdrawal period before processing. Kamphuis does not feel that is adequate so he chose to eliminate antibiotics in the last four weeks of his chickens’ life cycle.

A probiotic similar to that in yogurt is given to the chickens to combat harmful bacteria.

Another innovation is feeding the chickens a whole wheat diet. The wheat is purchased from local farmers who do not desiccate with glyphosates.

The idea was relatively new in 1988 when they first tried the whole wheat diet. He was told by various experts that whole wheat was a mistake.

A small percentage of wheat is fed to day old chicks and is increased as the birds develop. In their last week of growth, their ration contains about 55 percent wheat. The chickens also receive a grain mix that Kamphuis formulated with a nutritionist. No animal byproducts are used.

An elaborate computer system monitors barn temperature as well as water and feed intake. Walking through the barns every day, Kamphuis watches their behaviour and their droppings for any changes.

The computers, which Kamphuis installed himself, have reduced the chore level, leaving more time to pursue sales.

“Looking after the chickens is not much work. It’s the maintenance and the marketing,” he said.

Kamphuis and his wife have been in the poultry business for 17 years, but they have only been on this site for two years. They built the farm from scratch, which enabled them to develop a modern system that provides a healthier environment for the birds. The 4.5 metre high ceilings provide better air circulation. Water, used by the family and the chickens, is treated with ozone and filtered.

“This is the first indicator we have some sort of problem in the barn. The birds’ water consumption drops right off,” said Kamphuis.

They used to use formaldehyde to disinfect the three grower barns, but eliminated it. They discovered fewer chickens died after they stopped.

“That was one of the things that made me aware of what is going on.”

During the first days of life, the birds receive 23 hours of light. Once they reach the finishing stage, they receive 18 hours of light and a dark period for rest.

All the chickens are males because they grow better and carry less fat as they get bigger.

A local Hutterite colony handles the processing at a government inspected facility.

For more information visit: www.great-chicken.com.