The treatment and transportation of downer animals is a murky area for Canada’s livestock industry.

Provincial and federal legislation says animals that cannot stand upon arrival at the slaughter plant are to be treated humanely. However, regulations are often subjective and vary across the country.

“The rules are wishy-washy,” said Jackie Wepruk of the Alberta Farm Animal Care Association, which is working on a three-year study of downer livestock.

“We have no precise definition of undue suffering.”

The Alberta downer study began last April to assess the extent of the downer problem. The second year was meant to develop education programs for livestock handlers and the final year would assess what progress had been made.

Read Also

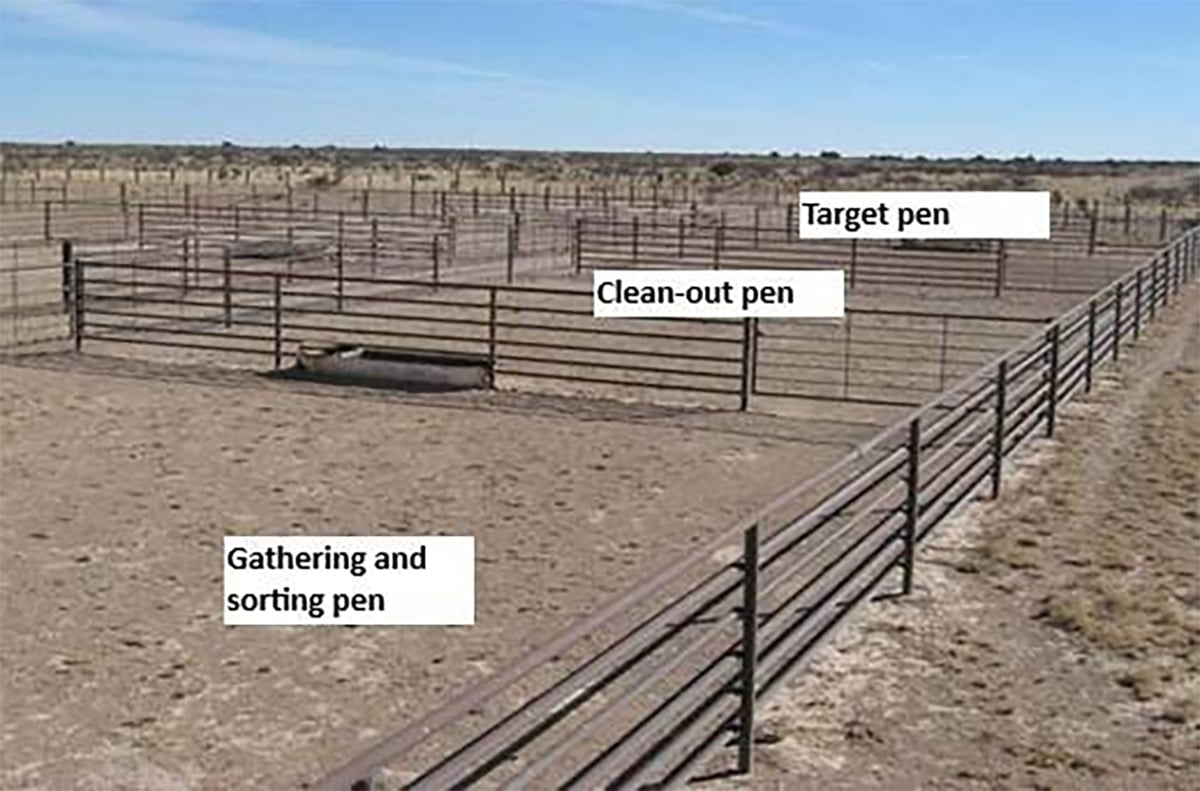

Teamwork and well-designed handling systems part of safely working cattle

When moving cattle, the safety of handlers, their team and their animals all boils down to three things: the cattle, the handling system and the behaviour of the team.

“The whole issue of downer transportation is up in the air right now,” she said.

North America’s two cases of bovine spongiform encephalopathy were detected in older cows that had gone down. The Alberta case was a sick animal taken to slaughter while the Washington case was a dairy cow that went to slaughter after it could not rise after giving birth.

Alberta SPCA enforcement officer Maurice Airey agreed there are grey areas.

“With provincial legislation there is a variance with the wording of the legislation and the degree of enforcement,” he said.

Each province has its own animal health legislation, but Ontario is the only province requiring veterinary certification of a downer before it may be loaded. Most provinces allow on-farm slaughter as an alternative way of dealing with downers, but legislation differs as to whether the carcass is restricted to private consumption.

In Alberta, the SPCA monitors auctions as often as possible, but constables say problems remain, mostly in beef and dairy cattle. Last summer most auctions refused to accept downers.

“The majority of auctions comply,” Airey said. “The problem is with them going direct to abattoirs.”

While it is often recommended that these animals be put down on the farm, that is often not the case. A Canadian Food Inspection Agency survey in 2001 looked at 19 slaughter facilities and three auction markets. It learned 7,380 nonambulatory cattle arrived at these sites, nearly 90 percent of them dairy animals. Less than one percent had been hurt in transit or accidentally.

Inspection led to carcass condemnation in 37 percent of the non-ambulatory dairy animals.

A similar survey concentrating on slaughter hogs and cull sows is in progress.

The Canadian Veterinary Association recommends a veterinary certificate accompany the animal. If it is passed for slaughter but cannot be moved humanely, the association recommends on-farm slaughter. Nonambulatory animals deemed unfit for slaughter should be humanely euthanized on the farm and the carcass disposed of in accordance with local regulations.

More federal and provincial slaughter plants are refusing to handle downers, while some charge a fee to put them down.

Following the announcement of the U.S. BSE case in late December, agriculture secretary Ann Veneman announced no downers will be allowed in the food chain.

Laws vary from state to state, but the American Veterinary Medical Association says animals that are down, but not in extreme distress, should be treated. Animals in extreme distress should be slaughtered on the farm or euthanized.