A single hair from a 2,000 pound bull can reveal more information about that hulking beast than could ever have been imagined 10 years ago.

Canadian purebred beef and dairy breed associations have submitted thousands of DNA samples over the years to the Saskatchewan Research Council’s laboratories in Saskatoon, which will soon change their name from Bova-Can Laboratories to Genserve Laboratories.

The samples, whether a hair or a piece of an ear, were initially used to verify livestock parentage.

However, scientific knowledge has spread to include multiple tests about the animal’s potential for a certain hair coat colour, better meat quality or milk production, said Dale Kelly, SRC vice-president of agriculture, biotechnology and food.

Read Also

Dennis Laycraft to be inducted into the Canadian Agricultural Hall of Fame

Dennis Laycraft, a champion for the beef industry, will be inducted into the Canadian Agricultural Hall of Fame this fall.

One of the newer services is a partnership with Merial Canada to offer the Igenity test. The technology has been available to Canadians for five years, but the samples were previously verified in the United States for important quality traits.

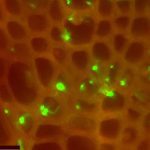

The genetic analysis technology can find multiple genetic markers for tenderness, marbling, quality grade, fat thickness, ribeye area, hot carcass weight, yield grade, coat colour, docility and calving ease.

Proving parentage remains the No. 1 reason for submitting samples, but more producers want to know what else is stored in the genetic code that can help them make better breeding decisions.

It would not replace the need for expected progeny differences,(EPDS) which is a formula-based selection tool that provides a genetic description of a sire for valuable traits. EPDs compare the predicted progeny performance of two bulls within a breed regardless of age or herd location.

“Marker selected genomics is actually being merged with EPDs and over time genetic evaluations will just become pronounced utilizing genotyping technology,” Kelly said.

Extra genetic information allows producers to understand more about their animals, but Kelly said DNA analysis is a tool rather than a magic bullet to build the perfect animal.

For producers running more than one bull, DNA parentage testing can help sort calves and target the ones that perform better in feed efficiency, weight gain or nurturing ability.

“We know a lot of the bulls walking the pasture that are firing blanks, so producers are paying money to feed a bull that is not being very productive for them,” he said.

Producers and breed associations also want information to help detect health traits sooner so they can prevent a genetic condition from appearing.

“Producers are going to know more about their individual cow herds than they ever had and that is going to help them sort out which lines are working really well and if there are health issues, Kelly said.

It’s up to producers to decide when they should test. Some tag everything at birth and submit a correlating tag with a tissue sample from the ear. Others provide hair or blood samples.

“It is up to the people who use the technology to figure out how to extract the value out of the marketplace. Everyone has a different approach.”

The Canadian Angus Association encourages the use of these tools, said manager Doug Fee.

“It would be an excellent idea to do far more extensive DNA testing than we are doing right now.”

With the rapid evolution of DNA science, more information is available almost on a weekly basis. While many breed associations use the SRC laboratory, other companies also offer testing. It may even be feasible to have DNA repositories at different sites.

“To have a big database is a fantastic idea,” Fee said. “Whether they should be in one place or multiple places, as long as it is tied in with the pedigree files the associations have, I don’t think it matters where it is.”

For example, the Angus breed submits about 4,000 samples per year.

“We require that every walking sire be parentage verified and on every 200th animal registered parentage verification is done,” he said.

“There are far more sires than dams on file.”

Genetic services could evolve into a new function for breed associations, allowing them to become more involved, Fee said.

“As this genome analysis is evolving, a lot of breed associations are thinking they have to get involved to identify the best genetics within their breed.”