Improved genetics have increased productivity but the industry may need new strategies to help rebuild cow numbers

SAN ANTONIO, Texas — Three decades of slow decline have forced considerable change within the entire North American cattle complex.

“The North American cattle and beef industries are undergoing rapid transition,” said Pete Anderson, director of research at Midwest PMS, a cattle nutritional supplements company in Colorado.

From the cow-calf to the feedlot sector, operations have left the business since the 1970s, he told the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association convention, which was held in San Antonio Feb. 3-7.

Their reasons were little or no profitability, outside forces such as bad weather, a desire to retire and farmland lost to richer bidders interested in urban development, cropping or recreation.

Read Also

Alberta cattle loan guarantee program gets 50 per cent increase

Alberta government comes to aid of beef industry with 50 per cent increase to loan guarantee program to help producers.

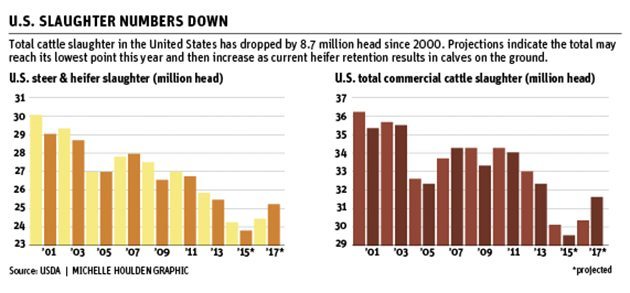

Cow herds have dispersed and in the last six years, 69 feedlots closed and 950,000 head worth of bunk space disappeared. Some operations converted to other purposes, such as dairy farms.

“We still have over-capacity,” Anderson said.

Packing plants also started closing, and 2.5 million head per year capacity has been removed. Still, over-capacity remains a problem so more may shutter.

“Who gets to live one day longer than a feedyard? A packing plant,” said Anderson.

Meanwhile the world is looking for more beef.

“Farming and food production are no longer local industries serving local markets. All of us in the beef business and the food business are part of a global marketplace,” he said.

Fewer cattle may be available, but the good news is that modern beef animals produce as much meat and milk as they did in 1975. More calves survive each year and grow larger and faster. Overall quality has also improved.

In the past, high performance cattle were considered to be the heavier muscled red or yellow breeds. Better genetics led to high performance and high grading cattle without heavy birth weights.

“We made such a transition in the genetic capability of our cow herd and the breeds we used. Now we have cattle of all breeds that can perform exceptionally well,” he said.

“That is a relatively new thing, and it has really made a positive difference.”

He thinks southern Minnesota used to have the best cattle in the business. There used to be hundreds of consistent, black hided cattle that grew well and earned their owners money because of their ability to hit carcass specifications. Now there are hundreds of thousands of similar type cattle across the continent.

“We didn’t just make them bigger, we made them better,” he said.

Bigger cattle with heavier carcasses are increasingly common. Better genetics, growth hormones, beta agonists and improved feeding regimes all contributed.

“Who even remembers a 600 pound carcass?” Andersen said.

Weight discounts were applied when they exceeded 850 lb., but that is no longer the case.

Most packers had a carcass weight limit of 1,000 lb. two years ago. Now that is virtually non-existent because the business wants the beef.

Bigger cattle cannot compensate entirely for the losses to the industry, so the cow herd must increase to get more calves.

Record prices in the last year may be the incentive needed.

“We have never had this strong an economic signal to rebuild the cow herd,” he said.

Corn prices are a key input and could influence decisions to expand.

“Feeder cattle will be worth a lot of money as long as corn doesn’t go to $8.”

However, the cattle business is risky and capital intensive. New partners may be needed to invest.

“I do not see a completely integrated model like pork or poultry have. There is more than (there) used to be, but I don’t think that is the way to manage through this,” he said.

Another shift for the industry is accepting imports of lower grade beef for grinding. Anderson said the U.S. herd should continue to produce high value beef because that earns the most money.

Success means meeting customer specifications and documenting practices. Consumers may be willing to pay more for high quality beef, but in return they are going to have more influence on that product. Practices such as animal welfare, antibiotic and hormone use must be documented.

“It is fair because we are asking them to pay twice as much as they did half a decade again,” he said. “They will pay a premium for stuff they like.”

Another way to get more beef on the market is to work with the dairy industry. The U.S. dairy sector has 9.3 million cows, and pregnancies result in 45 percent male calves. Some are used for veal, but many end up in the fed beef sector.

One consideration is to use beef bulls to produce heavier weight dairy calves to earn more money for both sectors.

An overall benefit to the feeding sector is to invest in people. Labour shortages are common, and employees need incentives to stay.

Corporate cattle feeding companies have already started training employees who can operate highly automated equipment develop the skills to manage a large feedlot.