OLDS, Alta. – Randy Kaiser never wanted to be just another cowboy.

He did not want to raise conventional cattle and deliver them to the auction every fall and accept whatever bid was offered that day.

Instead he found a new way to sell his naturally raised beef. Along the way, he became politically involved to help his business thrive.

“We don’t have to follow the norm and be the same as everybody else,” he told the crowd at his 10th annual Kaiser’s Celtic Cattle bull sale at Olds, Alta.

Read Also

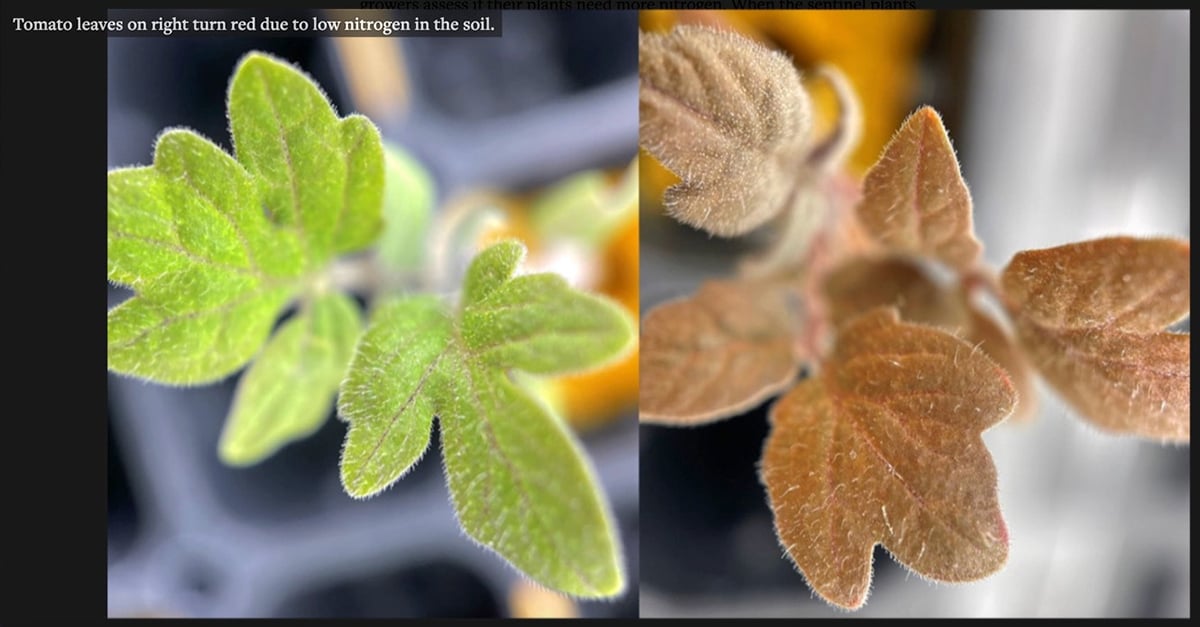

American researchers design a tomato plant that talks

Two students at Cornell University have devised a faster way to detect if garden plants and agricultural crops have a sufficient supply of nitrogen.

“You can’t just raise cattle and sell calves. It just doesn’t work anymore,” he said later.

“Anybody who is doing it has all their land paid for and they are eating off the equity of something else.”

Raised in the Ponoka area, Kaiser returned to the family farm after studying psychology in university during the early 1980s when interest rates were high.

At age 21, he bought the farm and assumed a six figure debt with double digit interest payments.

He had a commercial cow-calf operation and when he decided he wanted purebreds, he tried Limousin before exploring breeds such as Galloway and Welsh Blacks.

“We decided to try something different and it has worked really well,” he said. Kaiser developed predominantly black herds where the cattle are moderate in size with long hair and marble well on a grass diet.

“If you get people to look at the cattle, you can see there is nothing wrong with them. It is just getting people to look,” he said.

He has worked with Galloway breeders Hugh Crawford and Paul Froehler. Kaiser and Froehler formed the Canadian Celtic Cattle Company to supply a Calgary butcher shop and restaurants.

The beef must come from a Galloway, Highland or Welsh Black sire and preferably a British dam. No antibiotics are allowed after weaning, no growth hormones are used and the animals receive a special feedlot diet.

Kaiser uses ultrasound on his bulls to assess meat quality and charts their performance using DNA analysis for traits including marbling, tenderness, yield grade and docility.

The beef is sold at three Second to None Meats shops in Calgary that offer Alberta raised natural beef, pork, poultry, lamb and game meats. Kaiser often works behind the counter to meet the customers.

“It is definitely a marketing tool for us to be in front of the consumer like that,” he said.

Kaiser decided selling beef this way is the only way to keep the farm family alive.

“We decided the only way to do it is to integrate straight through to retail and have our own stores,” he said.

“It is a purpose for me. I could have been a lawyer or doctor but I decided to stay in the cattle business. I want to produce product for a consumer who is (conscientious) and who wants a choice. I have no interest whatever in supplying a conventional market that has no compassion and no interest in the farmer or the consumer, just the profit.”

Kaiser recently participated in an entrepreneurial boot camp to learn more about marketing.

He was among the first to sell calves on the satellite auction with limited results. He placed his bull sale on the internet and now has buyers from across Canada.

“You have to do what you can to survive. It is a little hard to keep up sometimes with the technology.”

Kaiser also set a floor price on each animal offered based on its cost of production.

“We can’t just keep asking. We have to stand up and say what we need.”

That willingness to examine new ideas led to his political awakening around 2004.

He read an article by Blackie, Alta., rancher, Cam Ostercamp, who criticized the handling of BSE and said the Canadian cattle industry was doomed without major changes.

He also met British farmer Mark Purdy, who speculated BSE was caused by environmental factors.

His next step was involvement in a BSE class action lawsuit against the federal government. Kaiser has worked hard to convince producers to defend their industry.

“I don’t like politics,” he said. “I have friends in all the groups but I don’t want to belong to any of them.

“I have a purpose. We all have a place on this planet and I think I found mine and that is to try and change something that is wrong.”

His son, Conrad, is not interested in agriculture but his 22-year-old daughter, Hailey, a veterinary technician, could become involved on the ranch.

“She’d love to be involved if there was some profit potential,” he said.

Recently, the divorced father earned his realtor’s licence to help add income for a planned expansion on his farm.

“I’m not quitting now. I’ll make a future.”