The introduction of mandatory cattle identification 15 years ago led to stormy protests about another program that would cost producers money with no discernible payback.

Producers were told the tags with individual identification numbers would carry confidential information required only for animal disease control and emergency trace back.

The unique identifying numbers are now seen as a good tool to protect against food fraud, back up branded beef program claims and improve production systems.

The good and bad points of the Canadian system were debated during a recent Alberta Beef Producers session on traceability.

Read Also

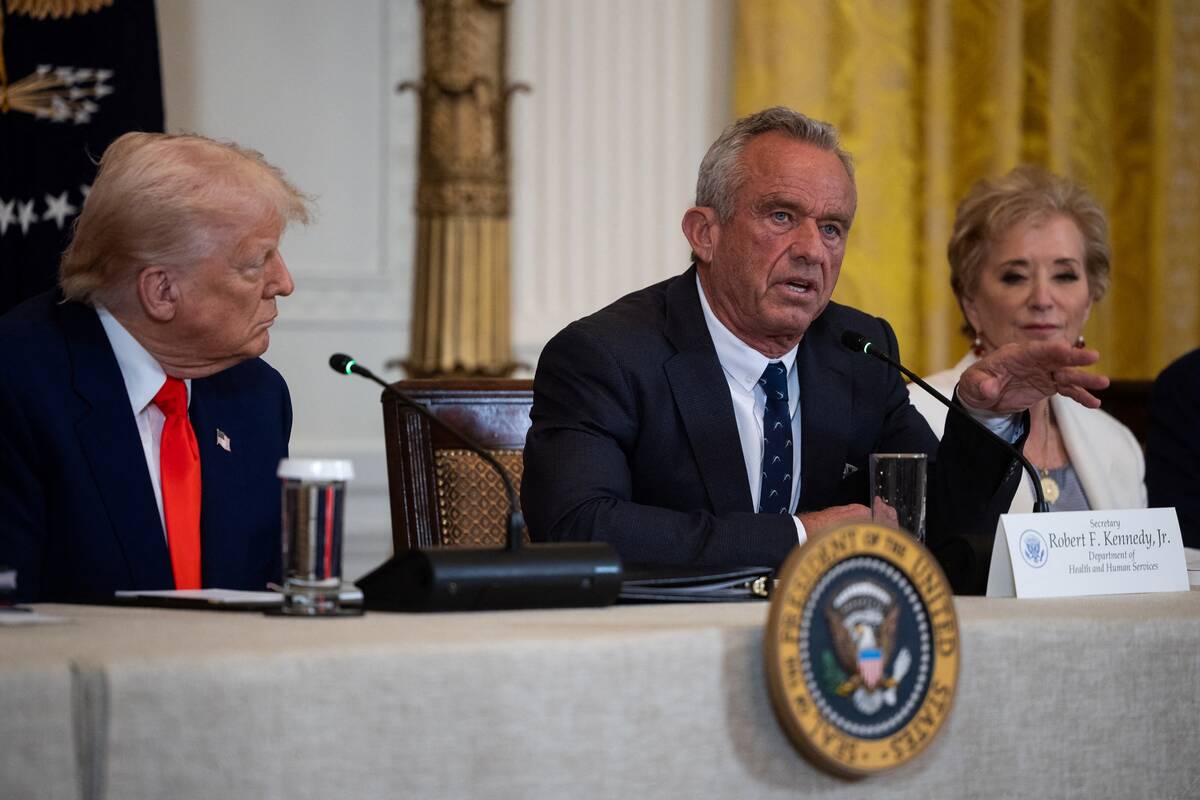

Draft ‘MAHA’ commission report avoids pesticide crackdown feared by farm groups

The White House will not impose new guardrails on the farm industry’s use of pesticides as part of a strategy to address children’s health outcomes, according to a draft obtained by Reuters of a widely anticipated report from President Donald Trump’s ‘Make America Healthy Again’ commission.

Brad Fournier of the Alberta Livestock and Meat Agency, which funded a study on the value of traceability, said the system has worked well for tracing the origin of diseases, but for many the greater benefit is added information for customers who are looking for specific product guarantees such as free range eggs or guaranteed tender beef.

“Traceability has both the public good and private good,” Fournier said.

“The consumer relevant program and brand management that is going to be growing exponentially in the next while has traceability as the backbone, but not the driver.”

Dave Moss of Integrated Traceability Solutions, which offers hardware and software systems for livestock trace back, said 20 countries have implemented full traceability for market access, and some trading partners could use its absence as a non-tariff barrier.

He said Canadians have been lulled into thinking their food system is safe and are not interested in discussions about databases and radio frequency ear tags.

“The consumers think we have a traceability system.”

Agriculture Canada researcher Tim McAllister said traceability boosts consumer confidence, but international systems are far from perfect.

Countries such as Japan and the European Union have invested millions on traceability, but not much auditing occurs.

“The systems are not as infallible as they want you to believe,” he said.

“I don’t think we should feel embarrassed about where we are.”

He said Canada cannot claim it has a foolproof system for disease traceability. Consumer trust would be put at risk if there was another major food recall on the scale of XL Foods last year and products could not be fully traced.

That is where major corporations are stepping in and building programs that are beyond a bare bones disease trace back system. They want higher standards to build a strong corporate brand.

One example is the Ontario Cornfed Beef program initiated by Loblaws. Among the qualifications for the program is DNA trace back through Identigen.

Mauricio Arcila, technical account manager with Identigen, said the company is able to follow the genetic fingerprint of meat and can promise horse meat is not mixed into ground beef and pork does not end up in hallal meat.

Arcila said the information can also help meat producers verify the source and genetic background of live animals, helping produce a more consistently high quality meat.

It could also open the trade door, he added.

Canada wants a free trade deal with Europe, and DNA fingerprinting could prove beef is free of added hormones.

Basic traceability is still taking baby steps at the grassroots level to build compatibility among databases and handle efficient animal tracking.

That is the job of the Canadian Cattle Identification Agency, which leads the Cattle Implementation Plan to implement traceability in the Canadian cattle sector.

Quebec is exempted because it has its own program, but the overall goal is to build a national multi-species data management system that is compatible with national standards and meets the needs of industry and government.

Premise identification of farms and places where animals gather is still needed., said CCIA manager Brian Caney, but streamlining is taking time because it is a provincial responsibility.

“It is a key piece to tracking movement, but the difficulty is you are dealing with more than 10 governments to try and get them aligned on the way they set their numbers up,” he said.

Some national agreements have been reached.

Recording group movement at commingling sites such as auctions is acceptable rather than individual scans of large groups of cattle. However, the agency database cannot handle this information at this time.

A national movement document is also at the design stage for each province to manage on its own. It is not a livestock manifest per se but will contain information about shippers and receivers, the producer’s name, address, premise identification, dealers’ names and addresses and livestock’s origin and destination.