Landowners in Western Canada’s oil country looking at the legacy value of their properties will need to consider how water is behaving deep below the surface.

“It looks like we probably have some liabilities beyond our current suspended and orphan wells because some of these are more or less open holes in some areas,” said Grant Ferguson.

Ferguson is a professor and hydrogeologist at the University of Saskatchewan. He and graduate students Keegan Jellicoe and Christopher Perra looked at how potable groundwater might be affected by pressure changes from practices such as enhanced oil recovery, saltwater disposal and hydraulic fracturing.

Recent data on how many prairie people depend on groundwater is scarce, said Ferguson, but it’s clear that it’s an important, even essential resource, particularly in rural areas. Provincial sources state that about 14 percent of Albertans, more than 30 percent of Manitobans and about 28 percent of people in Saskatchewan rely on groundwater for their freshwater needs. Pressure on these resources is likely to increase as surface water resources become inadequate.

“So we start to look on currently some of our major rivers, the Bow and the Oldman River through Alberta, it’s almost fully allocated,” Ferguson said. “So what happens next? We’re probably up against the limit of what we can use for surface water.”

This demand will become more acute with, for example, major expansion of irrigation such as the $4 billion initiative in Saskatchewan to further exploit the waters of Lake Diefenbaker. In times of shortage and drought, Ferguson said groundwater could be called upon as a backstop, so getting a handle on activities that might affect it is important. At the top of the list is petroleum extraction.

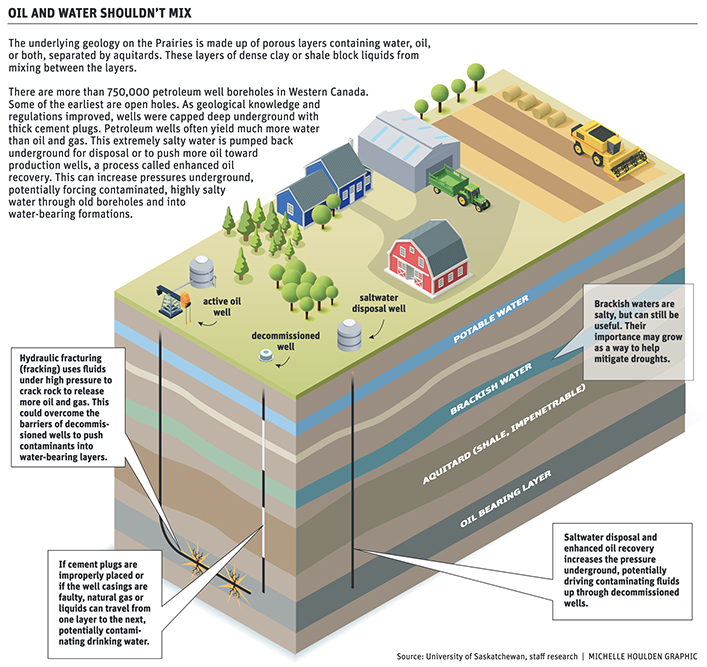

Since Leduc #1 in Alberta launched the petroleum industry in Western Canada in 1947, regulations about how to decommission wells evolved with improving technology and knowledge of deep geology. These deep structures include layers that hold liquids and gases in pores much like a saturated sponge, separated by dense, impermeable layers that prevent mixing.

The first wells received little treatment once they were played out, but eventually, decommissioning included pouring cement plugs tens of metres thick at several depths, to keep the porous layers separated.

With better extraction technology, the question of liquid volumes and pressures came into play. Oil wells typically produce a lot of water — often far more than petroleum. In the Williston Basin, home to the Bakken oil formation in southeastern Saskatchewan and the northern United States this water can be more than 10 times more salty that seawater.

For a larger copy of the graphic above, in PDF format, click here.

This water is often pumped back into the oil-bearing formations to push more oil toward production wells, a technique called water flooding. It can also be injected under extremely high pressure into oil-bearing rocks to fracture them (fracking), creating cracks to allow more oil and natural gas to be recovered. Finally, extremely saline waters left over from petroleum production are disposed of by pumping them back underground.

All of this activity creates pressure imbalances that can drive liquids up old petroleum well boreholes like juice being pushed up the straw of a child’s drink box. If the cement plugs are badly placed, if well casings are compromised, these highly saline, oily waters can potentially make it into potable water aquifers and contaminate wells.

“There are some pretty big volumes of fluid that have move around southeastern Saskatchewan,” Ferguson wrote in an email. “The resulting pressure increases are probably more likely to cause contamination of overlying shallow groundwater supplies than anything associated with fracking.”

While records are spotty for the early days of the industry, Ferguson said they are comprehensive starting in the 1950s and 1960s. It was this database, along with historical records such as the Glenbow Archives in Calgary that the researchers used for their study.

While the practice of fracking has long received a lot of attention within the context of water contamination, Ferguson said conventional water flooding and saltwater disposal need to be considered as well.

“Some of these issues are not really fracking issues, they’re oil and gas issues in general,” he said. “So that was sort of the jumping off point: is this a big deal or not?”

The distance between oil bearing and potable water layers varies considerably. In the Bakken formation, oil layers can lie more than two kilometres deep. Ferguson said heavy oil plays in western Saskatchewan and eastern Alberta near Cold Lake are typically 400 to 500 metres deep. And of course, outcrops of the oilsands formations are visible along the banks of the Athabasca River near Fort McMurray.

Definition of groundwater varies by jurisdiction. In Alberta, for example, it’s defined as anything more shallow than 600 metres. A typical potable water well is perhaps 100 metres deep.

The researchers looked at data from the Williston Basin in Saskatchewan as well as two oilfields southwest and northeast of Edmonton in Alberta. They found some older wells were abandoned in a way that left multiple aquifers connected between their cement plugs, allowing for mixing of ground waters.

Adding pressure to the system with large volumes of salt water could be making matters worse, but there is not enough monitoring to know for sure. For example, Ferguson said there are only about 70 monitoring wells in Saskatchewan, and these are set up more to monitor water levels than petroleum contamination.

Groundwater also moves at varying rates, he explained, citing stories of petroleum industry activity happening in the 1980s without incident, then “30 years later, there’s benzene detected in someone’s well.”

Ferguson suspects it may be a “slow burn” issue, but one that needs to be planned for now. He said the world will inevitably move away from oil in the coming decades, which will leave landowners and the governments of the day to deal with the problem.

“As of now, it doesn’t look like a widespread issue as we don’t see it,” he said. “On the other hand, groundwater has a long memory.”