Glacier FarmMedia – Canola growers might one day be able to tell exactly which subset of clubroot they can expect resistance for from the seed label.

That’s what Don Norman wrote in a recent issue of Grainews, a story then reprinted in the Manitoba Co-operator.

The spark of the story was a new proposal, where seed companies would — instead of a generic “susceptible” or “resistant” classification — mark their labels with details on which clubroot pathotypes the variety was resistant to.

Read Also

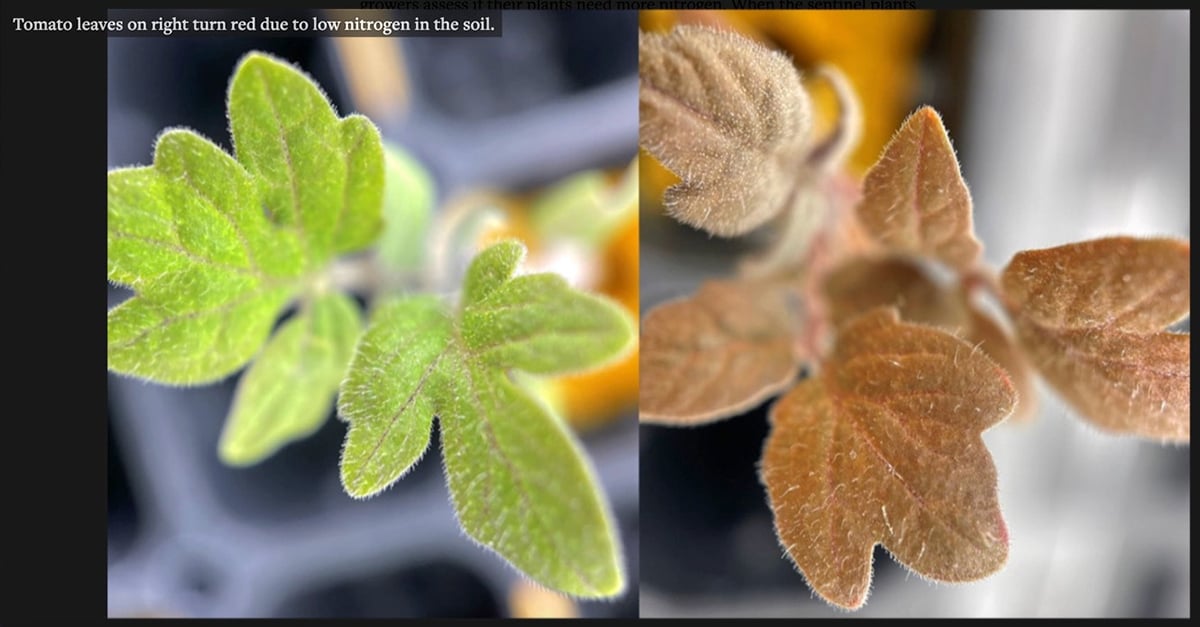

American researchers design a tomato plant that talks

Two students at Cornell University have devised a faster way to detect if garden plants and agricultural crops have a sufficient supply of nitrogen.

“The goal is to help farmers choose and rotate varieties more effectively, reducing disease pressure and preserving the usefulness of resistance over time,” Norman wrote.

It’s not the first time growers have heard that reasoning for a canola pathogen; it just wasn’t for clubroot.

Race testing for blackleg has been around for a while, and it’s been actively pitched by grower groups. The Manitoba Canola Growers Association, for example, has offered to foot the bill for one test per year for any of its members.

Knowing your blackleg race “can help you choose the canola varieties with resistance gene(s) that work on isolates present in that field,” a fact sheet overview of the program says.

In both blackleg and clubroot control, pathotype testing sounds like an elegant, high-tech solution for a sophisticated, high-tech age of farming. But knowing your pathogen race or pathotype is little more than an intellectual oddity if you don’t have the seed resistance information to compare.

That gap may limit the practical application of these tools.

Scientists have noted the rat race agriculture is in against the biology of blackleg. Blackleg virulence has shifted in recent decades, researchers and organizations like the Prairie Crop Disease Monitoring Network have noted.

“We have seen every year, really, where there are varieties that are rated R that have done really poorly,” Canola Council of Canada agronomist Clint Jurke told our reporter Jeff Melchior last year.

“They look completely susceptible in the field. So yes, there are cases where, if the grower is growing the wrong variety for that type of race in the fields, then they could have a pretty bad time with blackleg.”

The canola council admitted that there hasn’t been a lot of uptake on the race test, although Jurke maintained that it is still a relatively new service and that many producers don’t know it exists.

“And it is a little tricky as well,” he added. “Once you get that race test, it’ll give you some kind of crazy number … To take that to selecting the right variety, you might need a little bit of help.”

Basically, to get any real use out of it, a trained agronomist has to get involved. It’s not a tool that the farmer can usually make use of on their own.

The seed companies, meanwhile, told Melchior that it wasn’t as easy as slapping a sticker on the label.

Some companies do list major blackleg resistance genes, but it’s not standard across the industry. BASF does not, due to the complexity of the issue, technical service manager Jared Veness told Melchior at the time. About 10-15 blackleg races are the most problematic in Western Canada, but there are about 80 known, he said.

“Most fields that have blackleg issues have two, three or more races within the field. And even if you have the appropriate major gene matched up with the race that you’ve identified, you can still get disease from the other races that are present,” he said.

“At that point, you can make the possible improper decision to rotate your major resistance genes to a different one.”

Minor gene resistance provides further complication, he added.

Clubroot is complicated too. The proposed system would cover three main pathotypes, Norman reported, but there are about 47 known and, like the co-existing races of blackleg, there can be different clubroot pathotypes even in the same gall. The proposed system would focus on the three most common. There is also work happening, Norman noted, to get a better handle on the minor pathotypes so they can also be included in the system.

Part of Veness’s wariness on labelling came from from worry that farmers would view the labels as a “silver bullet,” when integrated pest management needs to be part of the conversation.

That’s not an unfounded concern. To quote a great movie, “Life will find a way,” and farmers have seen plenty of examples of how relying on genetic resistance alone can be a short-term fast-track that starts running into sudden walls.

If we need more knowledge to develop simple, grower-friendly communication on race-specific resistance, that’s fair. Maybe the goal even needs to change —a readily available online tool that navigates producers through the complex analysis rather than trying to distill it down into something that fits on a seed label. What else is artificial intelligence good for if not taking arcane data and turning it into something digestible and useful?

Whatever the answer, we can’t slow down on looking for it. The diseases won’t. Manitoba’s canola disease survey found basal blackleg infection in 77-85 per cent of fields between 2020 and 2024. That’s a lot of opportunity for the disease to further figure out the genetics that farmers have become reliant on to keep it in check.