Glacier FarmMedia – The cool, damp spring the Prairies are experiencing could lead to a bad year for cabbage seedpod weevils, which is bad news for canola growers.

“They seem to like it a little bit cooler, rather than very hot, and can suffer with great heat and very dry conditions,” Saskatchewan Agriculture entomologist James Tansey says. “That can give us a little bit of predictive power as far as their distributions and prevalence in the year ahead.”

Adult cabbage seedpod weevils (Ceutorhynchus obstrictus) feed on a wide variety of species in the brassica family but complete their larval development only in the seedpods of certain species of Brassicaceae, including canola.

Typically, there is a strong correlation between the ebb and flow of insect populations and their natural predators. But in North America, cabbage seedpod weevils have no natural predators.

Read Also

Sugar beet harvest underway in southern Alberta

Alberta Sugar Beet Growers hosts field tour to educate the public on the intricacies of the crop, its harvest process, and contracts with Lantic Sugar

“Because it is an introduced animal, it has escaped the regulation that it might normally experience with its natural enemies,” says Tansey, who did his master’s thesis on the bug.

The insect species originated in Europe; its documented debut in North America was in the Creston Valley of British Columbia in the 1930s.

“The thinking is that it worked its way south into the United States and found its way around the mountain system there into Alberta,” Tansey explains. “It was first detected in the Lethbridge area in 1995.”

The good news, said Tansey, is that a federal research station in Lethbridge staffed with some very capable entomologists identified the weevil as a potential problem for farmers and started the work to develop strategies to combat the pest.

But the bugs kept moving.

“From that point, it was an overland march,” Tansey says. “It’s a decent flyer, and it also hitchhikes in vehicles. It can travel relatively large distances in relatively short times, and by the early 2000s, it found its way into Saskatchewan.”

By the time it reached Saskatchewan, it was already well established in southern Alberta, causing economic woes for canola growers in the province.

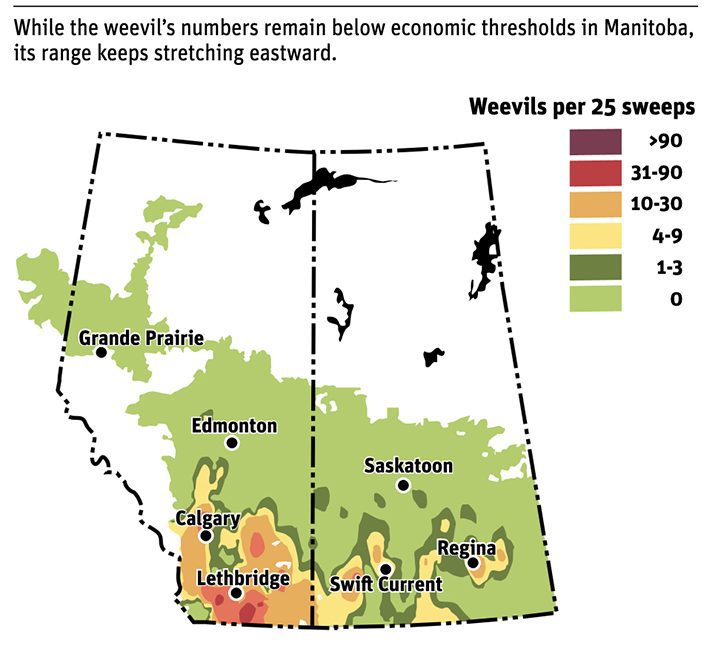

The weevil is also making its way into Manitoba. Provincial ag entomologist John Gavloski has been carrying out surveys in Manitoba to spot the bug. According to his 2023 survey, cabbage seedpod weevil levels are still very low and well below economic levels in Manitoba. However, with every survey, the weevil’s range expands eastward.

There is an eastern population of cabbage seedpod weevils that is well established in Quebec, Tansey adds, but it’s thought to be a separate population from the one that was first spotted in Creston.

According to the Canola Council of Canada, the adult weevil overwinters in the soil, often under leaf litter in tree shelterbelts, roadside ditches and woodlots. They emerge in the spring, with peak emergence occurring when soil temperatures reach around 15 C.

Following their emergence, adults fly to patches of early-flowering plants in the brassica family, like wild mustard and volunteer canola. They move into canola fields in June, when the crop begins flowering.

“The nice thing about this particular insect is that it overwinters as an adult, and it’s really attracted to the colour yellow,” says Keith Gabert, the council’s insect management lead. “We tell them to check the earliest flowering fields, and without a doubt, the cabbage seedpod weevils in the neighbourhood will be attracted to those fields.”

That predictability is what makes the cabbage seedpod weevil relatively easy to control.

“This is a pest we have learned to manage,” Gabert says. “We’ve had several decades of dealing with cabbage seedpod weevils. It really seems to make itself at home south of Highway 1 in and around that Lethbridge area, and growers there have considerable experience dealing with infestations.”

According to Gabert, the cabbage seedpod weevil survey maps provide a good indication of where infestations are likely to occur again.

“The maps are pretty clear that southern Alberta may have a population there, but it isn’t as far north as we’ve seen it in the past,” he says. “There is also a small hot spot west of Swift Current and a small hot spot east of Regina.”

Farmers in or near those areas should be actively scouting for the pests, particularly if their canola field is the first to flower. But Gabert warns farmers not to jump the gun when spraying for the insects. While they might be present in large numbers in a flowering canola field, they cannot do any economic damage until the plants are podding.

“You can have a lot of cabbage seedpod weevils on those yellow flowers and get excited,” he said. “But just step back a moment. If you don’t have a pod that’s half an inch long, it’s not big enough for them to lay an egg and can’t do any damage.”

If you can hold off until that first or second pod appears, Gabert says, you should only have to spray once for this particular pest.

“That’s their sole purpose in life: to perpetuate the species, sink into that pod, lay an egg and get those larvae feeding,” he says.

The thresholds for spraying are 25 to 40 in 10 sweeps, and in Gabert’s experience those numbers appear very accurate, he says.

“Hector Carcamo’s research indicated that you could sweep four times in a field—two pairs separated by 50 metres — to assess populations and be correct more than 90 per cent of the time,” Gabert says.

If farmers are seeing those levels, then it’s time to spray.

“We tell growers to spray between 10 and 20 per cent blue,” Gabert says.

While it hasn’t been widely adopted, Alberta Agriculture says trap cropping is the most promising cultural control method for managing the pest. Its web page dedicated to cabbage seedpod weevils says that by planting a trap border of early flowering field mustard (B. rapa) on the perimeter of a canola crop, the insects can be controlled by spraying that perimeter before they move into the main field.

The page also suggests later seeding of canola to help reduce weevil damage. But this method has to be balanced with the benefits of earlier seeding, which tends to produce higher yields in the absence of insect pests.

While the cabbage seedpod weevil is an introduced species and therefore has no natural enemies, there is growing evidence of parasitism.

“It does have some parasitoids that will attack it,” Tansey says.

The last work on that subject, done in the mid-2000s by Lloyd Dosdall, indicated numbers were relatively low, but the prevalence of parasitism was increasing.

“But the effect they’re having on populations is likely moderate at best,” Tansey says.

Fortunately, as mentioned, standard management practices appear to be effective at controlling the bugs.

“You really just need to scout,” Gabert says. “Especially if there’s a reasonable time lag between when the first field flowers and when the next few flower, it’s quite possible that you’ll drag most of them into the first field in the neighbourhood.”

The damage could be significant if high populations are left unchecked.

“Each of those larvae will eat three to five seeds, so if you have a lot of larvae, you’ll definitely lose yield,” Gabert says. “That’s why we’re comfortable with the threshold. If you’re over that threshold and you’re in an area that has significant numbers, they can definitely eat enough canola that you’ll have economic loss in your crop.”