Ever since H1N1 was officially declared a pandemic, we’ve been collecting information on hand washing and hygiene.

Why? Because “hand washing, when done correctly, is the most effective way to prevent the spread of communicable diseases,” says the Canada Safety Council.

It’s serious. Nevertheless, we are chastened to report discovery of a “yuk” factor in the course of sanitation research.

Because, while you and I wash our hands after every use of the bathroom, surveys indicate that others are not so diligent.

Read Also

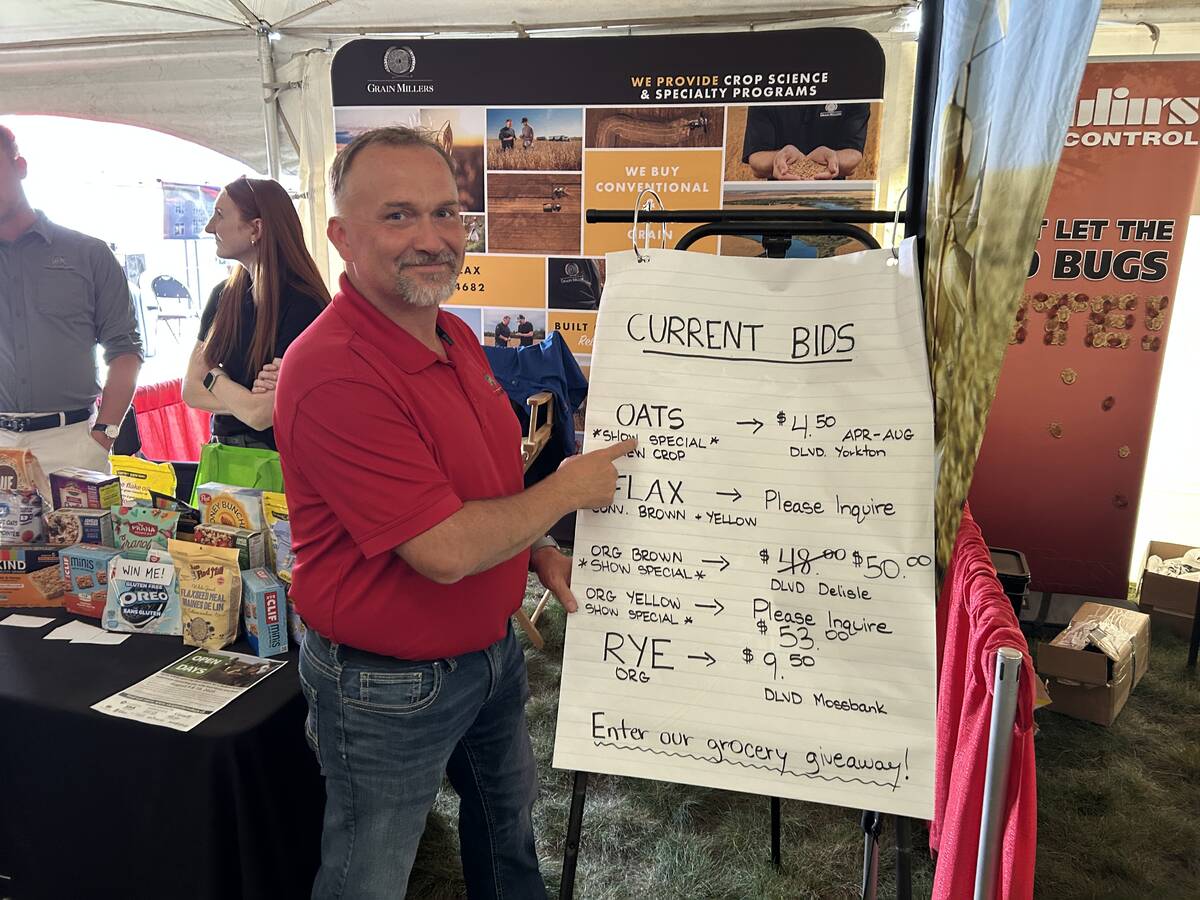

Canada’s oat crop looks promising

The oat crop looks promising and that’s a good thing because demand is strong.

A June survey by Harris Interactive, an American firm, found that 99 percent of those surveyed think other people don’t wash their hands each time and 48 percent said people wash their hands less than 50 percent of the time after using a washroom.

And a public washroom is as good a place as any to pick up the flu virus, along with various other unpleasant bacteria.

Besides the actual quantity of hand washing, there is a quality issue. Many food safety courses demonstrate technique by putting harmless colourless dye on the hands of course participants.

The people are then directed to go wash their hands and return to the classroom. Their hands are then exposed to ultraviolet light, which causes unwashed areas to glow green. Shoddy hand washing is uncovered.

The problem areas? Under fingernails, the areas between fingers, knuckles and the area near the wristwatch and other jewelry.

If the dye were full of dangerous flu viruses, these shoddy hand washers could spread it from doorknob to other hands, or from pillar to post, essentially.

Proper technique is to use soap and water, lather the hands and scrub for 15 to 20 seconds.

Once we started investigating sanitation, all kinds of things came to light. Not all are related to protection against H1N1, but they all make you stop and think.

The kitchen tap carries more harmful bacteria than the toilet handle in millions of homes, says London’s Daily Mail. The toilet handle was spotless in 75 percent of homes in a recent survey, while one-third of kitchen taps had unsatisfactory levels of harmful bacteria.

There are 400 times more viruses on the average desktop than the average toilet, says microbiologists Charles Gerba of the University of Arizona, quoted in the Washington Post.

Drying hands using paper towels is more hygienic than using hot air dryers or drip drying, says a survey by University of Westminster scientists. Warm air dryers of the type in public rest rooms can increase the average number of bacteria on your palms by up to 254 percent.

The moral of this story? Wash your hands and do it right!

Editorial Notebook

Earlier this month, Keystone Agricultural Producers attended a research and development conference for agriculture and food traceability.

Trace R&D was hosted by the University of Manitoba and focused on examining traceability technology and looking into a national traceability research strategy.

Traceability systems can increase productivity and profitability related to farm operations, processors and distributors. Though traceability does not guarantee food safety, it does provide a tool to help prevent food safety hazards from reaching more people when a problem occurs. Traceability is important to producers because it can offer market access, with buyers in many countries demanding it.

Consumers have different reasons for wanting to know where their food comes from. They may be fearful over food recalls and disease outbreaks. They may be looking for value added, or want to buy local, organic or non-genetically modified food. They may be willing to pay for a material or non-material value endowed in food, such as food associated with a particular growing or production region.

The question on how the costs and the values are shared with producers is yet to be answered, but it is clear that we need co-operation from all members in the value chain. However, so far this has been difficult to achieve.

We know identity preservation is important, but Canada lacks the ability to trace all food from farm to fork. Around the globe, developed and developing countries are further ahead of us in establishing traceability programs.

Producers and farm organizations must work with the government to develop a system that is rapid, complete, internationally recognized and nationally integrated. A nationally integrated system is necessary for us to open up new markets and maintain existing ones.

We must also help direct research and development in the field and be willing to fully participate in traceability.

Traceability key to farm future