Blood poisoning, also known as bloodstream infections and the medical term septicemia, are serious, whole-body infections.

They are a particular concern for young livestock species — calves, foals, kid goats and lambs — because they receive very little immune system support from their mothers.

Instead, they rely on colostrum, the essential first milk that is vital to their early immune system. It contains huge quantities of antibodies from the mother that are ingested and absorbed.

Read Also

Dry summer conditions can lead to poor water quality for livestock

Drought conditions in the Prairies has led to an decrease in water quality, and producers are being advised to closely monitor water quality for their animals.

These first antibodies are critical for preventing bacteria from establishing infections before the young animal’s own immune system gains experience with microbes, matures and takes over.

Without adequate colostrum intake as a newborn, these animals are defenceless against bacterial infections.

Bacteria may enter the bloodstream from a variety of sources.

Some type of damage or break in the body’s normal defence system, such as a skin wound, is needed for bacteria to get in. Examples include navel ill (umbilical infections), procedural sites such as docked tails and castration, respiratory infections and damaged intestines.

Common bacteria include E. coli and Salmonella, which spread throughout the body via circulating blood.

There are sites where bacteria tend to settle out, causing small local infections that can then invade deeper, triggering widespread inflammation.

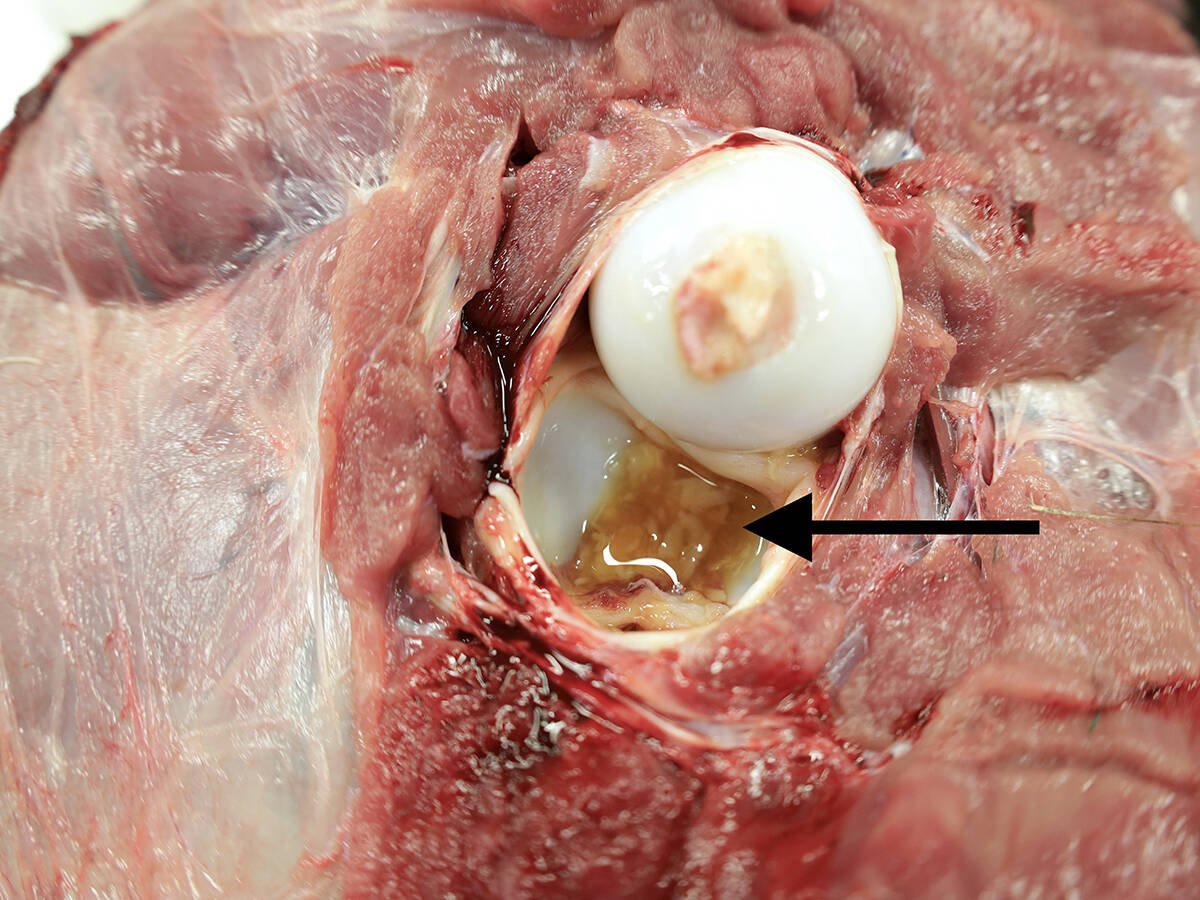

These include the meninges, which lines the brain, the joints and growth plates of growing bones, lymph nodes, spleen and liver. Sometimes the bacteria get trapped or settle out in the filtering parts of the kidney and even the small blood vessels of the heart.

Infection and subsequent tissue damage at these secondary locations is an issue. However, blood infections also cause serious, whole-body effects on the immune system.

Bacteria signal the body’s immune system to the presence of an invader.

Inflammation in the form of pus is full of damaging enzymes that are released in an attempt to kill the invading microbes. This inevitably damages the body as collateral damage.

Widespread inflammation triggers the release of chemical messengers that cause animals to change their behaviour. Observable clinical signs of illness such as reduced appetite, fever and inactivity are the result. These are the “ain’t doin’ right” animals.

Inflammation on this whole-body scale also sets in motion widespread blood vessel changes. Blood vessels become leaky, they dilate and allow inflammatory cells to stick to their walls. They also activate the blood’s clotting system.

A vicious cycle ensues where clotting in the smallest blood vessels then uses up all the available clotting factors.

In the final stages of this type of infection, widespread bleeding occurs in various tissues. Vets will examine the gums for small, pinpoint areas of bleeding, but it also occurs in internal organs and is visible during autopsy examinations. Animals die of shock as blood fails to circulate properly.

If an animal “goes septic,” as we say, then treatment usually involves an intensive, multi-pronged approach.

Antibiotics specific for the type of infection and anti-inflammatory medications such as meloxicam in livestock and “bute” or banamine in horses are mainstays.

Other supportive care may include intravenous fluids, warming and possible surgery if there is a primary infection site to resolve.

Animals are equipped with complex and effective ways to prevent bloodstream infections, but when they occur, the results can be serious.

Prevention is critical, and the best way to do this is by ensuring all baby farm animals receive adequate colostrum.

It’s also important to use good technique and clean tools for procedures such as castration.

As well, if a local infection such as navel ill is identified, it should be treated promptly and aggressively.