Michelle Hubbard, an Agriculture Canada researcher in pulse pathology who is studying how a chickpea-flax intercrop might control Ascochyta blight, says there are other tried and true methods of treatment for the disease for those who are unable to adopt the intercropping option.

Crop rotation

It nearly goes without saying that when addressing the disease in a chickpea crop, don’t plant them in the same fields year after year, or next to fields that had chickpeas on it last year.

Read Also

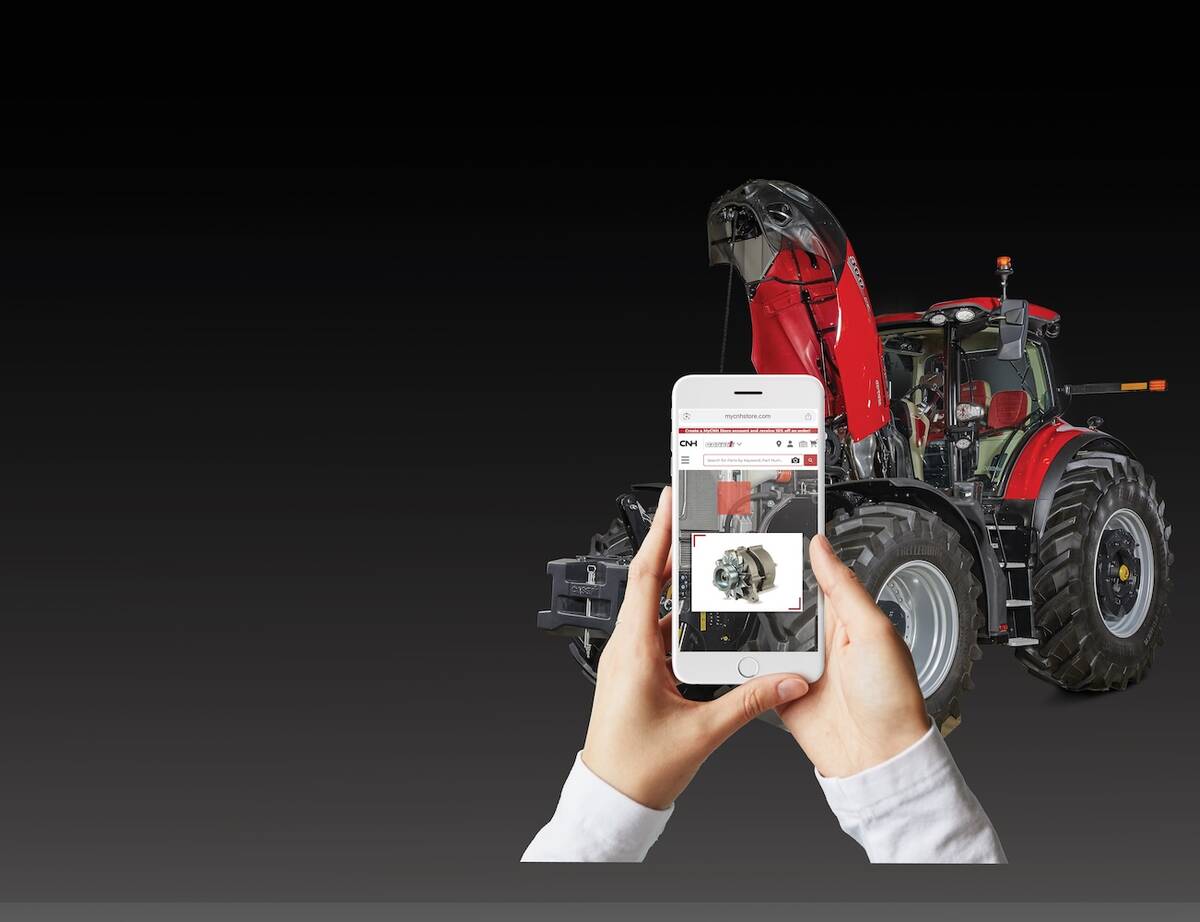

CNH launches photo feature to identify parts

Owners of CNH tractors looking for a replacement part can take a photo of the part and upload that photo to a website, which will then identify it and find the necessary replacement.

Residue from the previous crop can carry the infection over time, so it’s important to have at least three years between crops.

Planting Pattern

Due to the nature of the fungal disease, chickpea crops can’t be overly dense. Fungal spores will spread more easily from plant to plant with close proximity, and with the help of wind and rain.

And since Ascochyta can occur repeatedly in the growing season, plant proximity can significantly increase disease risk, Hubbard said.

Varieties and herbicides

Many new chickpea varieties have levels of genetic resistance to Ascochyta that can’t be found in the older ones.

Hubbard recommends always consulting the variety guide in the column of likelihood of disease and find one with as low a number as possible if disease is a producer’s greatest concern. The ratings run from zero to nine, with zero meaning no disease. However, no varieties are rated as zero.

Another thing to look at in the variety guide is if a variety is IMI herbicide tolerant.

“A lot of new chickpea varieties now are tolerant to IMI herbicides,” she said.

“But if a chickpea variety is not tolerant to them, or you use some other herbicide (probably that’s not registered for chickpea), or the conditions are too dry and there’s some other kind of herbicide damage, that could increase your risk of getting disease, too.”

She said it’s important to be careful when using certain herbicides, even if registered and commonly used. She gave the example of metribuzin, a Group 5 herbicide, which is often used.

“It can damage chickpea, and in some circumstances, sometimes farmers will think that’s still worth it because it’s an in-crop herbicide option and weeds can be a huge constraint. But it can damage the chickpea, and that damage can sometimes lead to more severe disease.”

Fungicides

Hubbard said fungicides are generally reliable and one of the most accepted methods of treatment, except Group 11 products, where there is a common resistance to treating Ascochyta.

A key part of fungicide application is the timing of it, she said.

As chickpeas flower, they become more susceptible to the disease, with disease presenting when the plant reaches seven or eight nodes. Sometimes it’s when the plant is a bit older, but it depends on conditions.

Information from her research trials showed that application before disease presentation or at first sign of symptoms doesn’t matter.

“So long as you’re diligent about checking for disease and so you catch it when it’s early, you could hopefully save money and use fewer fungicides by waiting until there is actually disease … as opposed to just deciding to use it regardless, without any disease difference or yield penalty or difference in the amount of diseased seed,” she said.