MINNEAPOLIS — In 2018, before the COVID-19 pandemic and the rise of artificial intelligence, David Montgomery was encouraging farmers and the agricultural industry to make a major shift.

The University of Washington geologist and author of the book Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations was a regular speaker at farm conferences across North America.

Related stories in this issue:

- Sustainability has a problem

- Road to sustainable food systems needs patches

- Producers lose their climate villain reputation

Montgomery was spreading the word on the benefits of cover crops, reduced tillage, diverse crop rotations and soil health.

Read Also

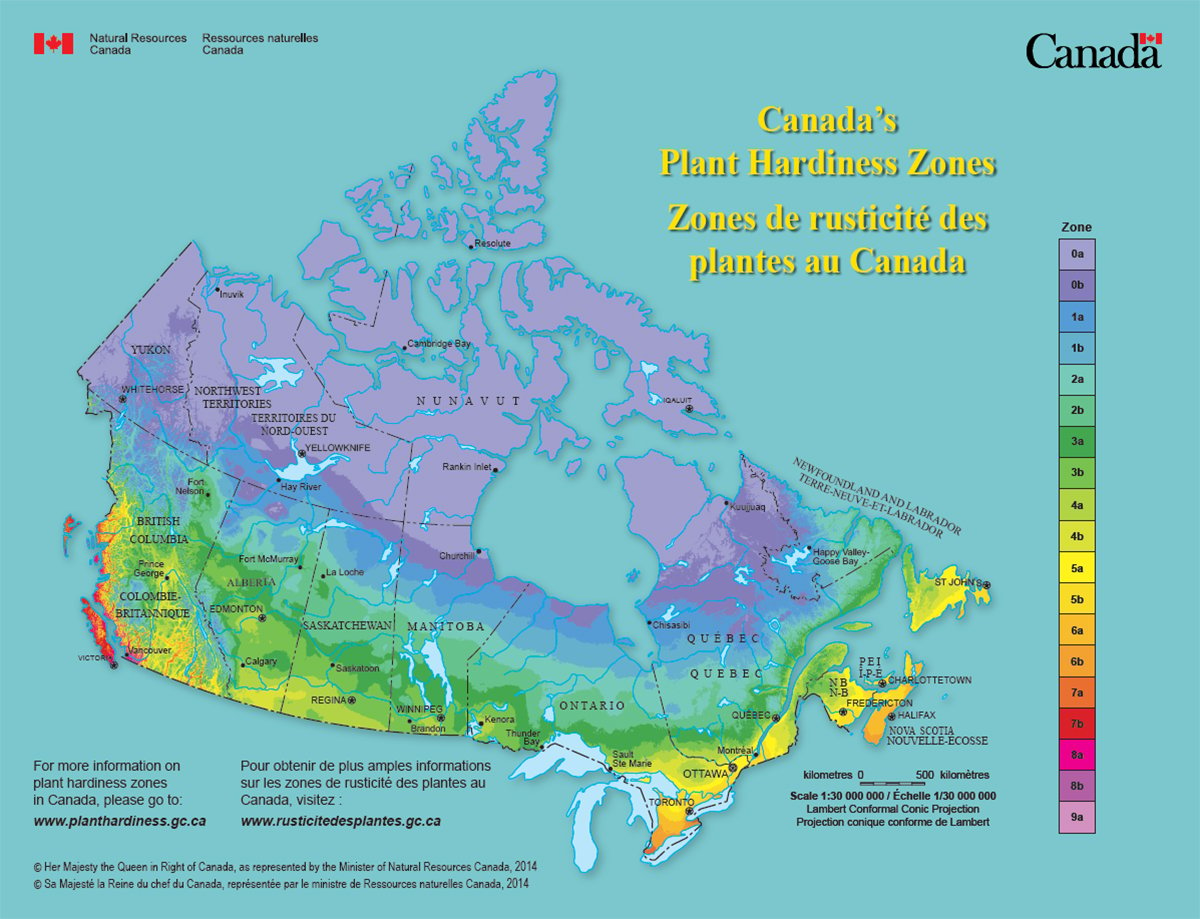

Canada’s plant hardiness zones receive update

The latest update to Canada’s plant hardiness zones and plant hardiness maps was released this summer.

He argued that a shift toward regenerative agriculture on millions of acres could make farms and food production more sustainable.

“This emerging fifth revolution, as I call it … I see it mostly being driven from the bottom up,” Montgomery said that year at a conference in Brandon.

“(There’s) a lot of interest from producers on ways to reduce the cost of inputs (and) ways to ensure their land is in better shape, when their grandkids get it.”

Grassroots adoption of this way of farming — with fewer crop inputs, keeping a living root in the soil year-round and more emphasis on soil health — is still happening across North America and in Western Canada.

What’s changed over the last six years is that major food companies took the reins on regenerative agriculture.

General Mills, for example, set a target in 2019 of advancing the farming practice on one million acres of farmland by 2030.

“Our voluntary programs partner with interested farmers in key regions where we source our ingredients, such as wheat, oats and dairy,” says the General Mills website.

Other food corporations followed suit, promoting regenerative agriculture from their position at the top of the value chain.

In 2021, PepsiCo said it would spread the adoption of regenerative ag on seven million acres of land by 2030.

A top-down approach can work, maybe, but it does have limitations. Some food and agriculture companies have realized that this movement should be handed back to farmers.

“(We) need to give growers the freedom to produce the (desired) outcome,” said a sustainability officer from a major crop nutrition corporation.

If Company X wants a farmer in its supply chain to cut greenhouse gas emissions, let the producer figure it out.

If a canola grower in Saskatchewan chooses an enhanced efficiency fertilizer and variable rate fertilizer to achieve the desired goal, that’s fine. The outcome is more important than the practice, the sustainability officer said.

Other firms also want producers to take the lead on climate-smart agriculture, but they’re taking a different approach.

They are providing training and agronomic support for a group of farmers to change practices on their land and share results within the group.

Then, those first adopters will share knowledge with other growers and the movement will spread outward from farmer to farmer.

The concept seems sound, but the fundamental question remains — what are the financial benefits for farmers?

If there isn’t a clear answer to that question, it seems unlikely growers and ranchers will embrace regenerative ag.

![A top-down approach [to regenerative agriculture] can work, maybe, but it does have limitations. Some food and agriculture companies have realized that this movement should be handed back to farmers, says University of Washington geologist David Montgomery. | File photo](https://static.producer.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/22141434/03-RKA121018_david_montgomery2.jpg)