When government grant money vanishes, so usually does the rural day-care centre.

It has happened most recently in British Columbia’s Okanagan Valley, but prairie experiments in the past decade have also failed, as has the Saskatchewan-led National Coalition For Rural Child Care, suspended since funding was cut in March 1996.

Carol Gott, from the rural Ontario county of Grey, says every provincial and federal government has programs for children. By lobbying as a community, farmers can make sure that money is used for child care, she said.

Read Also

Trade war may create Canadian economic opportunities

Canada’s current tariff woes could open chances for long-term economic growth and a stronger Canadian economy, consultant says — It’s happened before.

“We’re saying to really sustain (rural child centres) we need to set things up collectively rather than have little sites here and there that don’t survive.”

Gott, who has worked the past 13 years developing rural child care in Ontario, recently wrote a workbook to go along with a four-part video series on creating safe and caring places for farm children. The resource package was funded by the federal government and is offered free of charge by Alberta Agriculture.

Eric Jones, a farm safety specialist in Edmonton, says every farm family should see the series.

“This video takes a good look at the realities of raising children on today’s farms with bigger equipment, larger livestock herds and more pesticides and chemicals,” Jones said.

In the video, Gott says she is appalled at some of the choices people make for their child care. This includes leaving a child alone in a house with a baby monitor, leaving children to play in an empty pen in a barn while parents do chores, and letting children play at the side of a field while the parents do field work.

Besides the lack of care centres willing to handle farmers’ seasonal needs and long hours, many farm parents say centres are too expensive if they have more than one child.

But centres are not the only solution, said Gott. In her county the centres also send caregivers to farm homes. This offers flexibility to suit rural families and also makes the staff’s job more interesting by changing locales.

One option that governments have not yet allowed, Gott said, is subsidizing babysitters’ wages, although farmers can get summer grants for other farm labor.

Jane Bland, of the B.C. government, said a four-year care project funded by the federal and provincial governments ended in March 1999. It offered care for children of transient and migrant farm laborers who pick fruit. When the government money stopped, so did the project.

“The main problem is in order to provide care 12 hours a day and follow the licensing regulations on ratio of staff to children, your wages are much higher than you can bring in since most of the parents are low income,” Bland said.

Rural experience

The Lakeview Children’s Centre in Langruth, Man., has catered to rural families during the 10 years of its existence.

Director Jane Wilson said it has expanded to three other satellite centres and supplements parental and government funding with grants from agribusiness. Both Monsanto and United Grain Growers are contributing this year.

But Wilson is not willing to let government entirely off the hook.

“I have three sons,” she said. “Their wives work. It’s not because they’re greedy. I think the policymakers are going to have to realize that both parents must work to pay the bills.”

Wilson said the issue of safety has been linked to the child-care problem in recent years. She said children can be cared for in their own home, another’s home or in a centre in the nearest town. Her concern is that it be away from the farm work with its machinery, animals and other dangers.

“Rural child care doesn’t have to be in a centre,” she said. “Use Grandma. Don’t use the combine.”

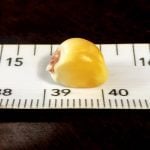

Since 1990, about 10 children have died each year on Canadian farms, making up about 20 percent of farm fatalities.

Children and the elderly die in greater proportion to their population on farms, which has led the federal government to fund a $500,000 project to analyze these age groups and farm accidents.