The organization tasked with uncovering rural homelessness in Alberta suggested that up to one percent of the population is experiencing unstable housing in small communities.

The findings, outlined in the Alberta Rural Development Network’s 40-page report released in late April, show there is an increasing need for more affordable housing in towns, villages and hamlets, said Dee Ann Benard, the organization’s executive director.

“For many people, there is no place for them to live that is affordable,” she said. “Most can’t afford to buy a home and there are very few rentals. Some landlords are also selective.”

Read Also

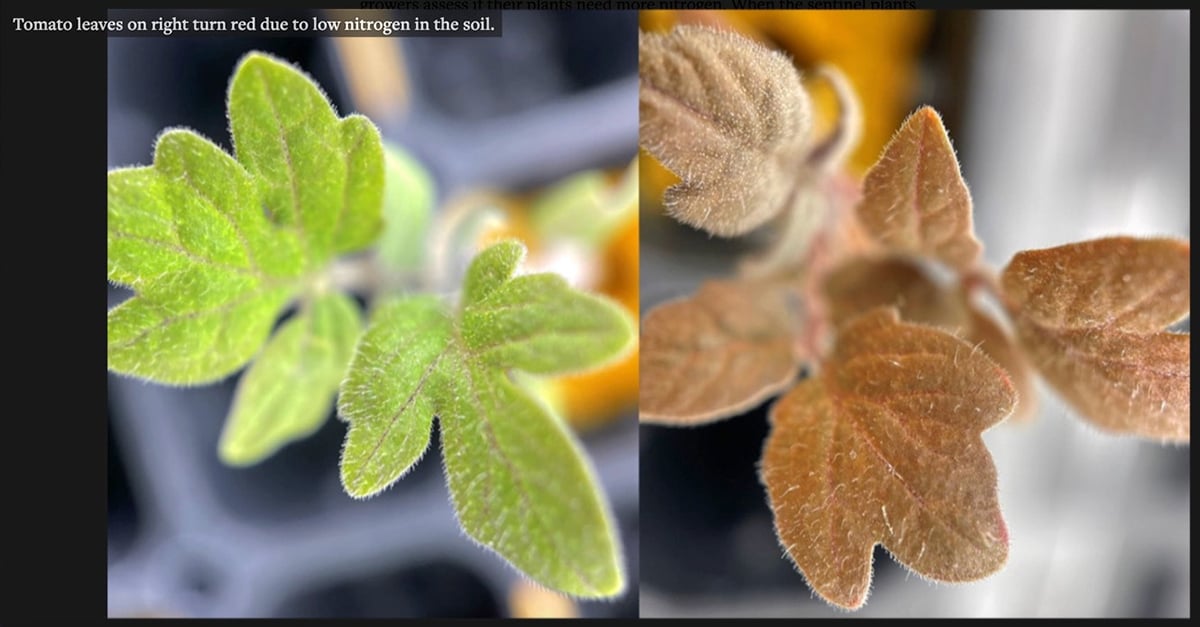

American researchers design a tomato plant that talks

Two students at Cornell University have devised a faster way to detect if garden plants and agricultural crops have a sufficient supply of nitrogen.

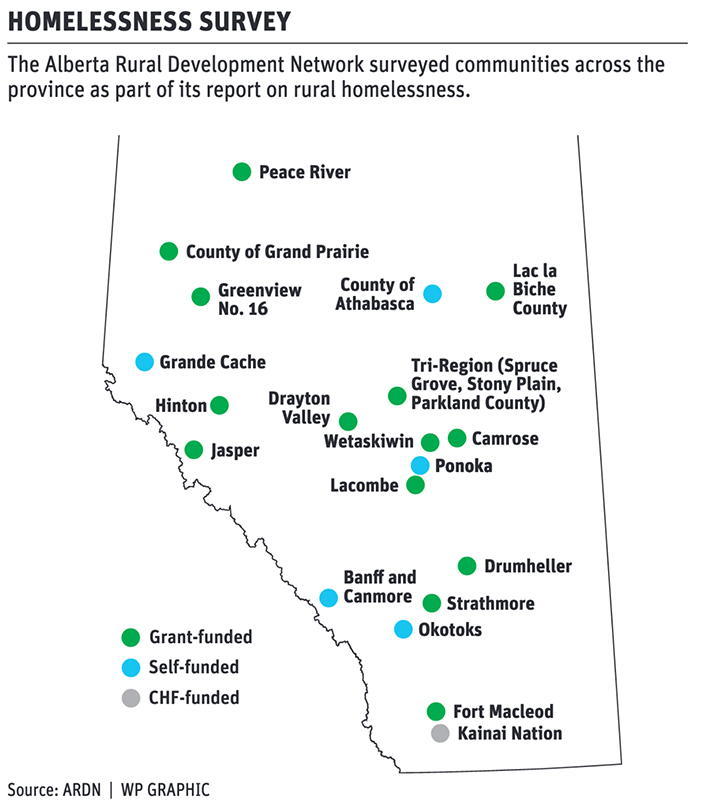

The Rural Homelessness Estimation Project report found that of 1,771 people surveyed in 20 communities, 1,098 people (0.37 percent of the population) said they didn’t have stable housing or were at risk of homelessness.

The number of at-risk people would grow to 2,997 (one percent of the population) if the 905 children and 994 additional adults living with them are taken into account. It can’t be guaranteed the additional people are facing unstable housing, the organization said.

The population of the communities surveyed was 291,531. It included towns and counties across the province. Participation was voluntary.

Benard said the numbers are likely higher than what was reported.

“There is going to be a lot of people missed in this survey,” she said. “Some people don’t access services or don’t get a chance to fill out the survey voluntarily. Others feel it doesn’t apply to them when it probably would.”

Rural homelessness looks much different than it does in cities. People may be couch-surfing, or living in a tent, camper trailer or abandoned house.

Homes could be extremely overcrowded, and they might be without heat or water, or they could be crumbling.

The report shows the reason people are experiencing unstable housing is because of low income and an inability to pay their rent or mortgage.

About 31 percent of respondents were employed, while 67 percent were unemployed.

It indicates people ages 25 to 44 were more likely to experience unstable housing, with people ages 45 to 64 also experiencing high rates.

Fewer people ages 65 and older reported having unstable housing.

Benard said seniors generally have more housing and programming options available.

“In most small communities, they have an old-folks home, a care home, so that’s not usually an issue,” she said. “It’s people who are working and often can’t make ends meet, as well as can’t live with parents or find a place to live, that are in more unstable situations.”

Many single people are this position. It’s generally harder to pay the bills with only one income contributing to the household, Benard said.

As well, the report indicated about 40 percent of respondents experiencing unstable housing were Indigenous. Indigenous peoples make up only 6.5 percent of Alberta’s population.

“Some communities we work with have nearby reserves,” Benard said. “Often times, when people come from the reserve and enter the community, they can face racism or other issues that make it difficult for them to find affordable housing.”

Respondents said there is a lack of shelter space in rural communities.

Benard said shelter space is needed, whether it’s a mat program or transitional housing. It’s all part of the need for affordable housing, she said.

“We need housing at all those levels,” she said. “Women fleeing domestic violence, for example, where are they supposed to go if there aren’t adequate services?”

The Alberta Rural Development Network plans to conduct another study with partners that work in community support services.

Benard said the future study may re-analyze the communities that took part in this project, and it could survey other communities.

A new survey would help them understand if homelessness is worsening or improving in communities. As well, it could help measure whether certain solutions are working, she said.

“We need to know what the issues are and what supports people need,” Benard said. “We need to know how we can fix this trend. We would rather not send people to the city.”