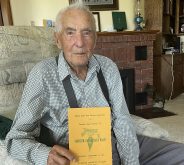

TULLIBY LAKE, Alta. – Stan and Dorothy Walterhouse are practical people.

When the Alberta farm couple learned the 161 head of cattle on their farm were going to be slaughtered and tested for bovine spongiform encephalopathy, they accepted the news.

“We got to do what we got to do,” said Stan as he helped push cattle through the chute to be tagged and inspected by federal and provincial officials before they were trucked to Moose Jaw, Sask.

“These cattle have a pretty slim chance of having it, but we’ve got to do it to get the border closure lifted,” said Walterhouse, as he sat on Hank, a seven-year-old gelding.

Read Also

Alberta crop diversification centres receive funding

$5.2 million of provincial funding pumped into crop diversity research centres

In April 1998, Walterhouse bought a group of 25 black heifers from the McCrea farm in Baldwinton, Sask. Seven months later, in November, the animals were sold to Donna and Bryan Babey at Sandy Beach, a few kilometres south. Canadian Food Inspection Agency officials believe the group of heifers may have contained the single black Angus that five years later became Canada’s first positive case of BSE in more than 10 years.

The heifer was tracked back to Walterhouse through his S bar W brand.

“I had a chance to buy some really good heifers. I guess I shouldn’t have,” said Walterhouse of his encounter with the now infamous black cow.

The Walterhouse cattle are not purebred, but they have a good reputation. In 2000, the Lloydminster exhibition association named the couple cattle producers of the year for the quality of their cattle.

Just two weeks ago, when the cattle were brought into the corral to be vaccinated, Stan thought they were the best group of cattle they’d had in a while, said Dorothy. She used a laundry basket to carry coffee, homemade banana muffins and puffed wheat squares from the house to the corrals for the workers.

Now the livestock on their farm along the banks of the North Saskatchewan River is limited to one horse, a cat and a dog.

Before the animals left the farm, three CFIA officials tagged the cattle and checked ear tags, two Livestock Identification Services brand inspectors shaved the shoulder, rib and hip of each animal to check for brands and the Walterhouse sons, daughters-in-law and a neighbour moved the animals into three trucks waiting in the field.

“We’ve got to do this. We sure need the border open to survive,” said Ed, their youngest son. He said once the farm was quarantined, he could predict the outcome.

“You just have to prepare yourself,” he said.

Ed’s wife, Audrey, said they’re taking their pragmatic cue from Stan.

“Your heart’s a little heavy today, but what can you do? Stan’s got a really good attitude about it,” said Audrey, as she inserted fence posts behind the cattle to keep them from backing down the chute.

The quarantine will stay on the farm until the cattle test negative, but they won’t be the last cattle on the farm, the family said.

“This is my life. I’m in the cattle business. I’ll get some more. It’s not life or death. If someone died in the family, that would be serious,” said Stan.