Managing injuries | Athletic therapists are an important part of modern day rodeos

When a rodeo cowboy hits the dust, chances are he will limp over to a team of athletic specialists who can help ease the pain.

Since 1983, the Canadian Professional Rodeo Sport Medicine Team has been helping these athletes recover and get back in the saddle.

“We co-ordinate care prior to the rodeo, during the rodeo and after the rodeo,” said Brandon Thome, who runs three athletic therapy clinics when he’s not on the rodeo circuit.

The concept was modelled after a similar program in the United States.

Read Also

Trade war may create Canadian economic opportunities

Canada’s current tariff woes could open chances for long-term economic growth and a stronger Canadian economy, consultant says — It’s happened before.

In the first year, University of Calgary athletic therapists Dexter Nelson and Terry Donhauser and exercise physiologist George Kinnear volunteered their services at the Cloverdale, B.C., rodeo, Ponoka Stampede, Calgary Stampede and the Canadian Finals Rodeo in Edmonton.

Last year, 62 practitioners — athletic therapists, massage therapists and chiropractors — attended several rodeo schools and 132 professional performances across Western Canada.

Another network of physicians, sport medicine doctors and orthopedic surgeons provided post-injury care.

In total, they travelled 22,000 kilometres with a mobile clinic. If there was more funding, they would attend more events, said Thome, vice-president of the team.

“Our goal is to be at one rodeo every rodeo weekend, so the cowboys can see us at least once,” he said.

At first, therapists were volunteers, but in recent years sponsors and levies from the Canadian Professional Rodeo Association, rodeo committees and private donors have paid for the service.

While rodeo cowboys may appear to be thrill-seekers with a high pain threshold, many realize that without proper medical attention they could suffer long-term injuries, said Jill Bruder, who operates a sports medicine clinic at Pincher Creek and is marketing co-ordinator for the team.

Attitudes have changed and more cowboys are taking responsibility for their health and wear protective gear.

“They are different than other pro athletes. If cowboys don’t ride, they don’t get paid,” she said. “Most take our advice. If you don’t ride for two weeks, you will have a better season,” said Bruder.

A big change came when the CPRA ruled bull riders 18 years and younger must wear a helmet. When they turn pro, they continue using protection.

“You see that gradual turnaround wearing helmets now. The older competitors who grew up riding bulls and steers with just the hat on, they say, ‘why would I wear a helmet?’ ” said Thome.

“Many times it’s a critical injury that gets them to wear a helmet.”

The teams also attend rodeo schools to educate students about injuries, concussions, sprains and strains and how to tape injuries, as well as how to warm up and cool down.

Nutrition on the road is another topic and advice is offered on managing sore backs after driving 14 to 28 hours to get to the next event.

Students seem more receptive to the advice because many are also high school athletes whose coaches taught them some of the same conditioning techniques.

“I think the young guys treat it more like a professional sport, so they’re doing conditioning in a gym, they are listening to advice, doing yoga and doing things that will make them a better athlete,” Bruder said.

“They don’t just get on a horse and ride.”

Sometimes a competitor needs advice from peers or family members to convince them to take it easy.

“Nobody wants to see their kid get hurt multiple times. Wives are good if we want to make sure somebody doesn’t ride,” he said.

At a major rodeo like the Calgary Stampede, paramedics are on hand and see the cowboy first.

At smaller events, competitors may go directly to the mobile sports medicine van for assessment and treatment.

Depending on the severity of the injury, they may get an ice pack, an order to rest, a referral to a sports medicine physician or an ambulance could be called.

Research is another function of the team.

Dexter Nelson and Dale Butterwick of the U of C faculty of kinesiology have conducted research on critical points of injury, finding that the head and chest are the most vulnerable.

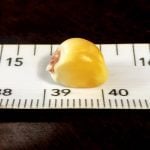

However, the type of injury often depends on the event. Their findings can help design helmets and vests that provide better protection for specific events, rather than using modified hockey equipment.

They have also learned timed events result in more chronic problems as opposed to traumatic injuries, said Thome.

A steer wrestler comes off a horse at 20 to 30 kilometres per hour to catch a calf. If he turns his foot the wrong way, an injury can result. A saddle bronc rider might catch his foot in the stirrup and accidently rotate his leg the wrong direction and hurt his knee.

Novice bareback riders between the ages of 18 and 21 have a higher rate of hand and wrist injuries because they’re still growing and may not be strong enough to hold the horse.

Female competitors commonly hurt their necks and shoulders or hit a barrel and damage a knee.

Researchers compared rodeo with high-contact sports like football and found there was a lower incidence of injury among cowboys.

“It is no different than any other sport. Sports in general are hard on your body,” Thome said.

“Your first initial thought about rodeo is, ‘oh my God, those guys are tough. They get hurt all the time.’ But that is not really true,” he said.

“Catastrophic injuries are very few and far between.”