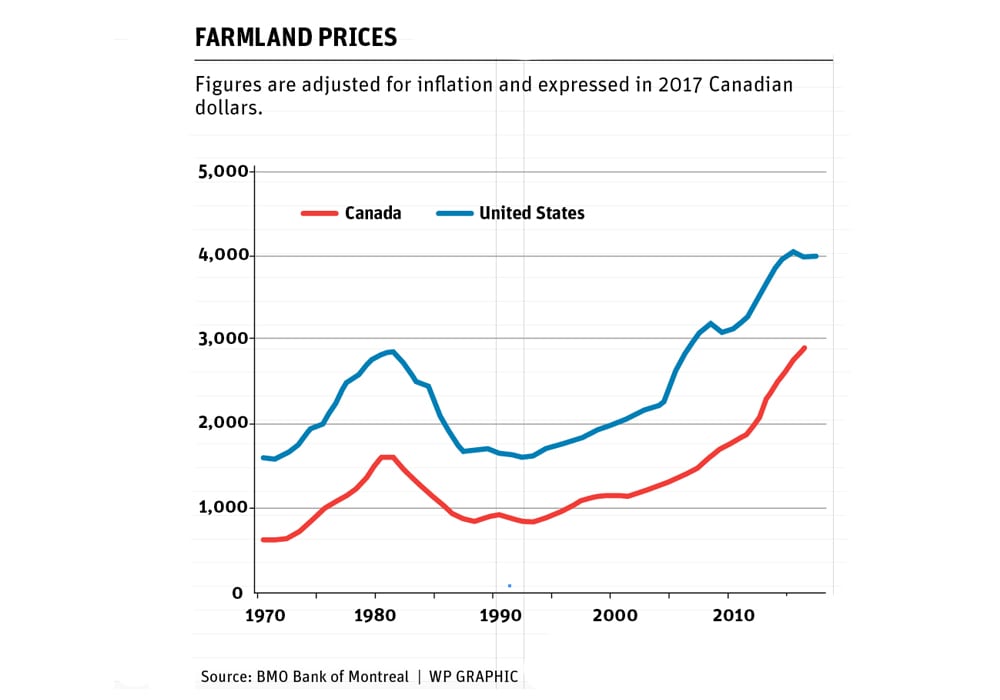

The price of farmland in Canada has roughly tripled over the past two decades, even after adjusting for inflation.

Despite these gains, it’s worth being cautious any time an asset price turns skyward. Land prices have crashed before and nobody wants to be caught.

To gauge the future prospects for farmland, we should look at factors that have driven its meteoric rise:

- Stronger commodity prices: After adjusting for inflation, Statistics Canada’s broad measure of agricultural prices has risen more than 20 percent since the mid-2000s amid growing global demand.

- Solid productivity growth: Genetic innovations and the adoption of precision technologies have allowed farmers to reduce costs and squeeze ever more production out of a given acre.

- Low interest rates: Interest rates have been exceptionally low since the 2007-08 global financial crisis, which has made it economical to bid more for land.

Read Also

Proactive approach best bet with looming catastrophes

The Pan-Canadian Action Plan on African swine fever has been developed to avoid the worst case scenario — a total loss ofmarket access.

Unfortunately, all three of these factors and other agri-business irritants are turning against farmland prospects:

- On the commodity pricing front, oversupply has abated within the past 12 months but remains burdensome.

- In the recent past, farmers have been shielded by an exceptionally well-timed drop in the loonie. The loonie is expected to appreciate only gradually over the next few years, but it will still put increasing pressure on the Canadian agriculture sector as our export-dependent commodities become more expensive.

- Rising interest rates. After a difficult decade, the Canadian economy has now largely recovered from the global financial crisis and the plunge in oil prices that began in 2014. With the economy near capacity, the Bank of Canada has already increased rates from a low of 0.50 percent last year to 1.25 percent today and is expected to reach a neutral 2.50 to 3.00 percent range in mid-2019. An unexpected uptick in inflation could spur even higher rates. Rising interest rates will raise financing costs, weighing on farm earnings and, potentially, land prices.

- Geopolitical and trade issues often use agriculture as bargaining chips to enhance other agenda items, which creates uncertainty for producers and investors.

- It is also possible that land prices have been pushed beyond justifiable levels by buyers hoping to replicate past gains. This can occur in any rapidly advancing market and raises the risk that land prices could drop sharply if deteriorating conditions triggered a rush for the exit. This factor, in our view, will mean the difference between a pause in land value increases and an outright decline in land prices.

Given the forces at play, it appears unlikely that farmland’s recent strong value gains will be repeated any time soon.

As always, but especially at this stage in the cycle, BMO is emphasizing caution and making the following recommendations:

- Consider “what-if” scenarios: Hypothetical calculations can help producers understand how they would be affected by a drop in commodity prices, lower land prices, an increase in interest rates, or all three simultaneously.

- Re-evaluate balance sheets: The farm sector’s debt-to-asset ratio is in line with long-term norms, but is higher than before the 1980s farm crisis. Producers should ensure they are comfortable with their borrowing levels and, if not, could consider diverting earnings or divesting assets to reduce debt.

- Reconsider maturities: Borrowers who are wary of rising interest rates may consider locking in a fixed rate. Variable-rate borrowing has been the winning choice over the past decade, but that may not be the case ahead.

- Take a long view: A decline in farmland prices would be far less consequential for producers who plan to hold and operate their land over the long term.

John MacAulay is senior vice-president and divisional head for BMO Bank of Montreal’s prairies-central Canada division.