Nobody likes to wait. Whether it’s in line at the grocery store or online waiting for software to upload, even five minutes of waiting can be difficult.

Bryan Johnston, who grew up on a farm near London, Ont., is hoping to make money from that basic human aversion to waiting.

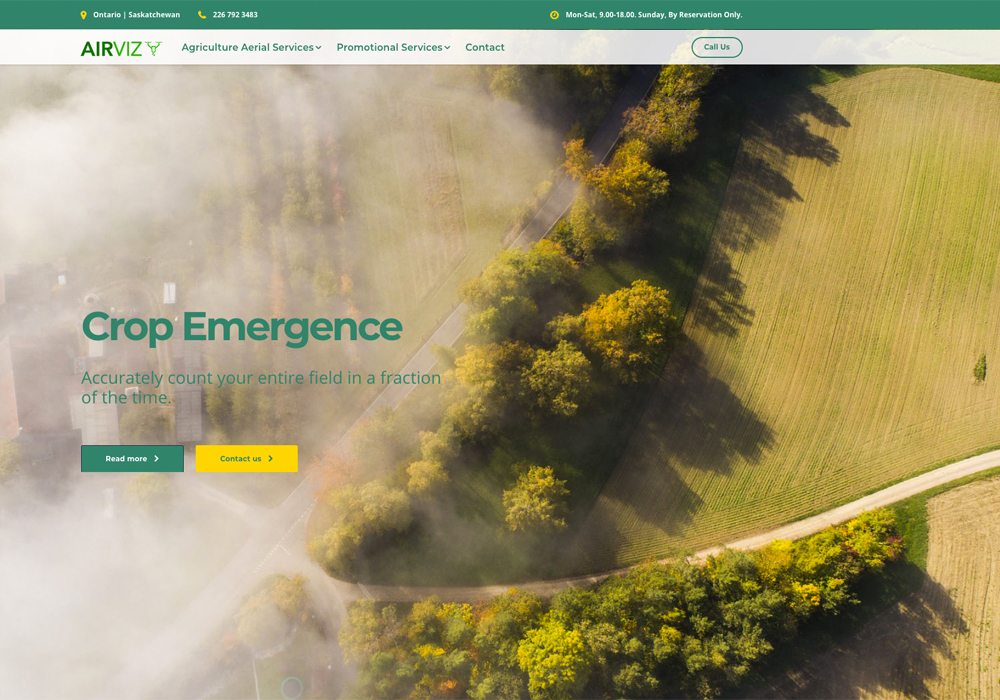

Johnston and his business partner, Alex Dodds, have started an aerial agricultural services company called Airviz.

The aerial services part is drones, or unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs).

They plan to fly drones over farm fields in Canada and provide growers with almost instant feedback on the condition of their crops.

Read Also

Growing garlic by the thousands in Manitoba

Grower holds a planting party day every fall as a crowd gathers to help put 28,000 plants, and sometimes more, into theground

“Our business plan is we fly it (an agricultural field) frequently throughout the season and give you immediate results,” said Johnston, who graduated from the University of Guelph in December with an agricultural business degree.

“That allows the farmer to go in and intervene (right away).”

Intervening could be spraying a piece of the field where disease has developed, re-seeding a portion of the crop where plants failed to emerge or adding fertilizer to a part of a field that is under-performing.

Johnston and Dodds can provide quick results because of the drone technology now available.

In 2016, when a drone camera and other sensors took pictures of a crop, it could take about a day before a computer processed the images into a map of the field.

Now, it’s possible to generate a similar map of the field in less than two minutes.

The new technology means that drone services companies can provide rapid information and growers can act on that information immediately, said Matthew Johnson, owner of M3 Aerial Productions in Manitoba.

“Maybe they’re not going to spray (the crop) that instant. But maybe check those areas (of concern) and make a plan for later that day.”

Companies like M3 and Airviz can provide almost instant information to growers because software firms have developed shortcuts for processing the imagery generated from a drone flight.

Johnson uses software from Sentera, a Minneapolis company. Sentera, in a company document, explains that it’s new technology is called QuickTile.

“QuickTile Maps may be generated on any Windows laptop with AgVault software, and can show full colour, normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), and near-infrared (NIR) crop images — all in a matter of seconds,” the company message states.

An NDVI map breaks down a field into green, yellow and red patches, which are indicative of plant development and crop health.

Before software like Quick Tile, it took much longer to produce such a map.

A drone would take a few hundred pictures and then a high-powered computer would process the data in three or four hours, at minimum. The process produced an orthomosaic — a large image pieced together from many overlapping images.

Alternatively, a drone pilot could upload all the images to the internet.

“Most people are going to be uploading them to a server somewhere … a company will stitch it for them and send back the stitched (photo),” Johnson said, explaining that could take 24 hours.

“Now at the side of the field, we can do this Quick Tile NDVI. It doesn’t have to process much. Even with no internet connection … it’s just relying on your computer’s processor.”

The Quick Tile map isn’t as sophisticated or detailed as an orthomosaic. Nonetheless, the Sentera document shows that the two methods produce similar results.

Johnston and Dodds didn’t say what type of software they use, but it’s likely they have comparable technology.

Dodds, a fourth year English major at Ontario’s University of Waterloo, isn’t your typical English major. He is taking a digital arts minor at Waterloo and in his teens he started a software development company with his brother.

“My brother and I have made a couple of mobile apps, a few web apps for desktops for various companies here in Waterloo and in Oakville.”

He got interested in drones three to four years ago and started using them for photography and videos.

“I had no idea I would fall in love with it as much as I did,” Dodds said. “There’s an aspect of freedom that you get from it that you can’t really attain from anything else, except something like skydiving or actually flying a plane.”

That passion for drones evolved into a part-time business and a job.

Dodds started producing marketing videos for houses and apartment buildings. He then flew drones for a property management company, where part of his job was using drones to inspect apartment windows.

Around the same time, Johnston was also experimenting with drones. He was producing videos for himself and for neighbours near his family’s farm.

Dodds met Johnston through a mutual friend and after a number of discussions, they realized they had the drone and software skills to start their own business.

Last year, they tested out their technology on soybean and corn crops at Johnston’s farm near London. Johnston used the instant feedback to monitor disease pressure from things like sudden death syndrome in soybeans.

“We (could) find the areas that were most at risk. You could tell from … the NDVI algorithm that those areas were really hurting.”

This growing season, Dodds and Johnston are launching their business. Johnston has recruited a few clients who farm around London and he’s also hoping to sign up farmers in Western Canada.

He now lives and works in Regina but on the side Johnston promotes Airviz and its aerial services.

Dodds is still in school but he’s committed to drones and their potential in the ag industry. This summer Dodds hopes to be busy flying drones over farm fields in Canada. Longer term, he envisions a future where a drone pilot isn’t part of the business model.

“My five-year plan is to make both hardware and software that will be able to do this completely autonomously, with no pilot needed whatsoever.”