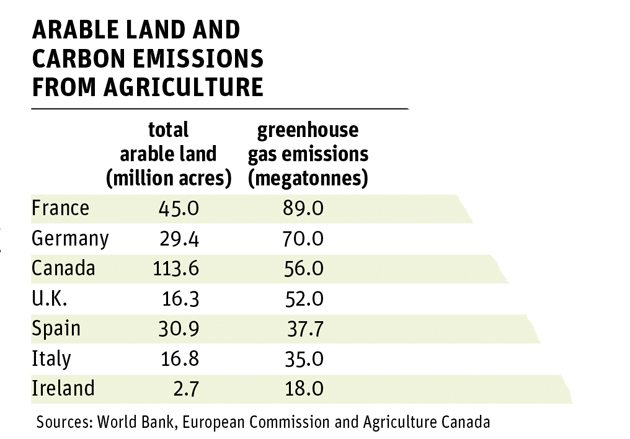

Canada is often listed as number seven in the world when countries are ranked by arable farmland.

The United Kingdom is more like 40th, considering that Canada has eight or nine times more farmland.

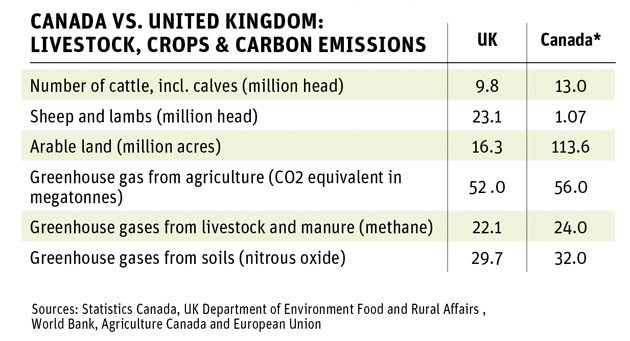

However, the U.K. and Canada produce almost the same amount of greenhouse gases from livestock and crop production: 56 million tonnes in carbon dioxide equivalents in Canada and 52 million tonnes in Britain.

Read Also

Farming Smarter receives financial boost from Alberta government for potato research

Farming Smarter near Lethbridge got a boost to its research equipment, thanks to the Alberta government’s increase in funding for research associations.

Canada’s agricultural emissions would be less than 48 million tonnes if carbon sequestration is taken into account from practices such as conservation tillage.

It would seem improbable that Canada’s greenhouse gas totals would be similar to Britain, which is a minnow in global agriculture, but several factors explain Canada’s relatively low number.

Brian McConkey, an Agriculture Canada scientist in Swift Current, Sask., who studies greenhouse gases in agriculture, said three factors drive emissions:

- use of nitrogen on crops

- the number of ruminants (cattle, sheep, goats)

- the amount of rice paddies

“(And) those vary from country to country,” he said.

“Without drilling down into the details, it’s hard to make comparisons at a national level.”

One factor working against Britain is climate.

Wetter countries with damp soils, such as Britain, will emit more nitrous oxide from the soil and farmers will apply more nitrogen to compensate for the loss. That means Britain has much higher nitrous oxide losses than Canada.

Britain also has 23 million sheep, and many of those animals gain weight by grazing.

“If you’ve got a lot of sheep … grazing on rough browse, you can have a lot of emissions relative to the amount of meat production,” McConkey said.

Canadian farmers are much more efficient at producing meat, he added.

The Beef Cattle Research Council released a study in January showing how production efficiency is key to curbing greenhouse gases.

Government and university scientists compared beef production between 1981 and 2011 and found that feed efficiency and other advancements made it possible for farmers to produce the same amount of beef in 2011 as in 1981 with 27 percent fewer slaughter cattle and 24 percent less land.

“The story in Canada’s agriculture is that emissions have remained relatively constant (while) production has increased very significantly: livestock products and grain,” McConkey said.

“We’re doing really well in terms of getting more product out there per (unit) of greenhouse gas emissions.”

Producing more food with the same amount of emissions is the only option for farmers because lowering the total isn’t feasible, McConkey said.

“I don’t know of any country that’s really seriously looking at absolute emission reductions (from agriculture),” he said, because nations will not sacrifice food security to cut emissions.

“If we dropped our production we could definitely drop (Canada’s) greenhouse gas emissions … but people are going to still eat. Somewhere that food is going to be produced. If it’s (grown in) a less efficient (country) or you’re clearing the Amazon to produce (that food), you are expanding emissions in a global sense.”