We once took for granted the easy movement of goods and services around the world.

Global trade flourished and just-in-time inventory management was the norm — until, that is, the spring of 2020, when everything changed.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought new additions to our vocabulary, such as “social distancing,” “remote working” and “Zoom.”

Read Also

Livestock leads Canada’s farm economic outlook

Forecasts by a major Canadian farm lender featured good and bad news on the financial health of both farmers and Canadians at large.

“Supply chain” was another, as stuck-at-home consumers began a shopping frenzy just as Chinese factories, where most of the goods are manufactured, began closing because of the virus.

The world has pretty much moved on from COVID, even though it continues to kill thousands of people around the world.

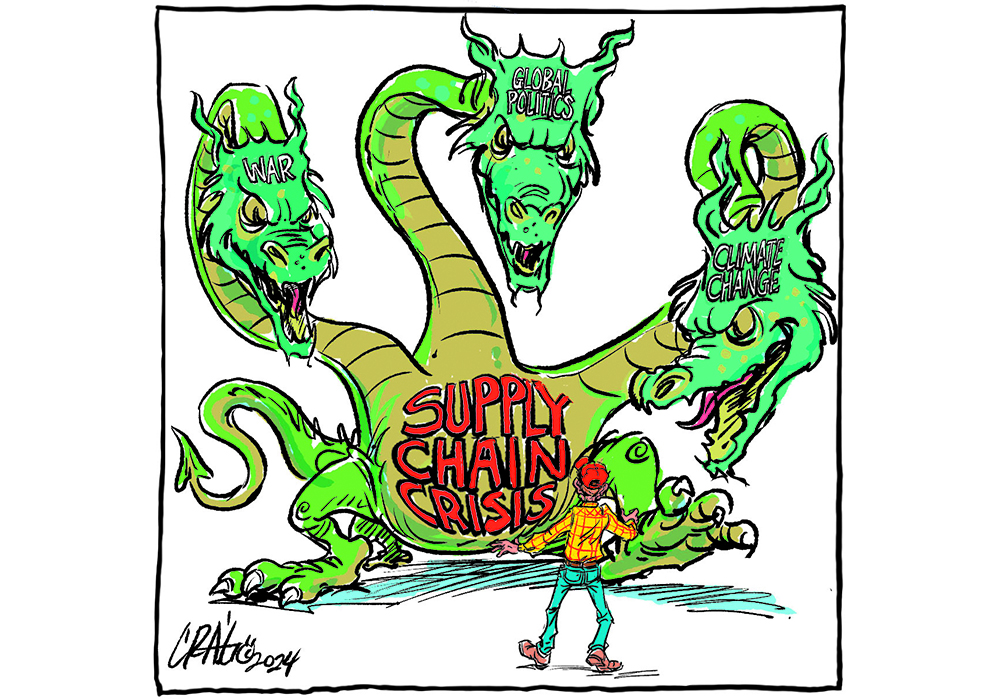

The supply chain crisis, however, remains for a variety of reasons.

Top of mind this summer for Prairie farmers was the labour dispute at the country’s two major railways. These kinds of disruptions have played havoc for decades with efforts to move farmers’ products to market.

This one was different, of course, because it affected both railways at the same time. As devastating as it could have been, a major disruption was avoided when Ottawa intervened, and life as we know it will continue.

Meanwhile, bigger threats are developing that could have more long-term consequences for global trade. In a recent newsletter, New York Times journalist Peter S. Goodman wrote about the ground-shifting developments that threaten to turn the new world order on its head.

“The supply chain is like the electrical grid — something we take for granted, as long as the lights turn on when we flip the switch,” Goodman wrote.

“But now we’ve endured the equivalent of a blackout, forcing us to contemplate what systems we are depending on — and how to make them more reliable.”

China is one of the bigger factors driving this potential shift. The pandemic forced us to acknowledge how reliant we have become on one country, and now that country is increasingly unreliable.

The autocratic nation, under an autocratic president, is more willing to throw its weight around to get what it wants, and that includes trade.

A good example is what happened to Canadian canola producers when China closed the door on imports because of the Meng Wanzhou affair, or to Australian barley producers after their government called for a review of China’s role in the spread of COVID, or to Norwegian salmon producers after the Nobel peace prize was awarded to a Chinese dissident.

Global trade has always been politicized to some degree, but now it is also being weaponized.

Just look at Russia’s efforts to stop Ukrainian grain from reaching the world, or its natural gas blockade in response to the European Union’s support of Ukraine, or rebels in Yemen disrupting shipping through the Red Sea in response to Israel’s war with Palestinians.

And the threats are not just geopolitical. A changing climate is also posing a major obstacle to global trade. For a real-world example, look at how an unprecedented drought in Panama is restricting movement through the vital canal that bisects that country.

It’s no easy feat to wrap one’s head around the fundamental changes in a global trading regime that we once took for granted.

One possible solution is to stop buying goods from unreliable sources, even if they are the cheapest supplier, and start looking for suppliers that are more reliable.

This option could ultimately lead to more manufacturing at home, but what that global retraction could eventually mean for Canada’s agricultural exporters is a frightening prospect.

There are no easy answers, but as producers of products that are mainly exported, it’s time Canadian farmers begin to face the fact that the world they once knew could be about to fundamentally change — and not necessarily for the better.

Karen Briere, Bruce Dyck, Barb Glen, Michael Robin, Robin Booker and Laura Rance collaborate in the writing of Western Producer editorials.