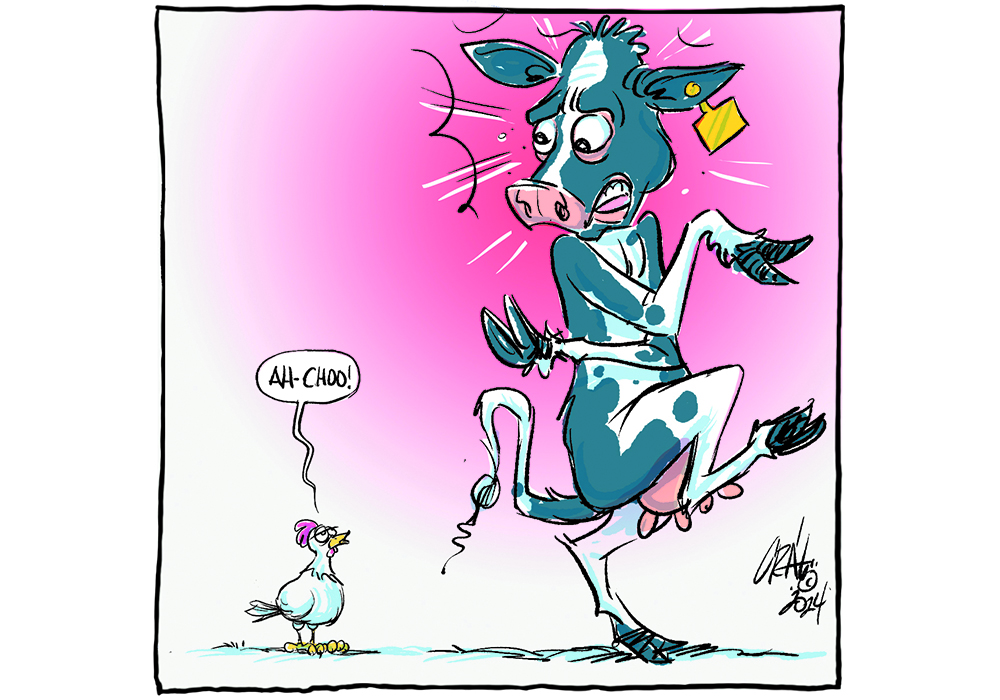

As Canadians warily eye the highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) outbreak in the U.S. dairy herd, one thing should be certain: watching and waiting isn’t enough.

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency has taken steps to keep the virus out of the country.

It has required negative HPAI test results for lactating dairy cattle imported from the United States to Canada, conducted enhanced testing of milk at the retail level to look for viral fragments of the virus and facilitated the voluntary testing of cows that do not present clinical signs of the disease.

Read Also

Higher farmland taxes for investors could solve two problems

The highest education and health care land tax would be for landlords, including investment companies, with no family ties to the land.

But considering how high the stakes could be, there is an argument to be made for more proactive measures.

And make no mistake, the stakes are high.

The virus, which has wreaked havoc in the global poultry sector for years, has the ability to infect mammals.

It has jumped from birds to cows, cows to cows, cows to cats that drank unpasteurized milk, and in three cases, cows to humans. There is no evidence yet that the virus is spreading from human to human.

While two of the three dairy workers who have caught HPAI from their cows came down with nothing more than pinkeye, the most recent case was a respiratory illness. That’s worrisome enough, but in the rare cases where humans have contracted avian flu from poultry, the death rate is 50 per cent.

The COVID-19 pandemic was bad, but those kinds of HPAI numbers in the human population would be catastrophic.

So, what more should Canada be doing? Are we prepared if the virus shows up in domestic dairy barns?

Governments and industry should prepare a vaccine supply and make sure dairy producers and their workers have access to it.

The same goes for personal protection equipment for dairy workers.

In the United Sates, workers and their advocates complain that producers aren’t making PPE available or informing them of the risks, even as the virus continues to be found in cows.

We can’t let that happen in Canada. A plan is needed now to ensure that if the worst happens, cow-to-human transmission is stopped in its tracks.

This country is in a good position to prepare for HPAI, considering all the work done to prepare for African swine fever and to stockpile vaccine for a potential foot-and-mouth disease outbreak.

Perhaps it’s time to use our experience with ASF and FMD to get ready for HPAI.

The laser-sharp focus on ASF and FMD preparation is driven by the dire economic consequences that would result from finding these diseases in Canada.

The potential human cost in the wake of an HPAI human outbreak, while harder to quantify, is alarming.

Another takeaway from HPAI’s jump to dairy cows is that the time of drinking raw milk has surely passed.

A study published recently in the New England Journal of Medicine found that mice fed raw milk contaminated with HPAI became infected with the virus, adding to evidence that consumption of unpasteurized milk is not safe for humans.

The bottom line is that Canadians — not only regulators but also producers and consumers — must increase their vigilance when it comes to HPAI.

Complacency is our enemy.

Karen Briere, Bruce Dyck, Barb Glen, Michael Robin, Robin Booker and Laura Rance collaborate in the writing of Western Producer editorials.