Harvest time always brings the urgency of getting the crop off the fields as fast as possible, but that need for speed must be balanced with the need to avoid damage.

Research at North Dakota State University looked at the issue, beginning with dry beans because their value is particularly vulnerable to issues such as cracking, breakage and seed coat blemishes.

What they found was cereals such as wheat, barley and oats are pretty tolerant of even repeated handling, but corn was less so. Soy was the most vulnerable, as are pulse crops.

Read Also

Wildfires have unexpected upside this year

One farmer feels smoke from nearby wildfires shrouded the July skies and protected his crop from the sun’s burning rays, resulting in more seeds per pod and more pods per plant.

In an article for SaskPulse, agronomist Bruce Barker writes that such crops should be moved as little as possible and as gently as possible. This means conveyors rather than augers — or if necessary, augers at reduced speed.

Winter handling requires particular care.

“Lentil, fababean, pea and dry bean seed should not be handled at temperatures below –20 C, as the seed is more susceptible to chipping and peeling at low temperatures,” he writes.

Chickpeas are particularly delicate because the “beaks” on their irregularly shaped seeds can easily break and compromise the seed coat.

Barker also recommends bean ladders to minimize the drop height and therefore the speed at which the crop hits the bottom of the bin. Cushion boxes on the bottom of the spouts on larger grain handling systems serve the same purpose.

“The idea of a cushion box is it’s going to retain a bit of the crop there, so whatever is coming down the spout is essentially hitting against more crop, which is a bit of a cushion,” said Ron Kleuskens, technical product representative with grain handling and storage company AGI.

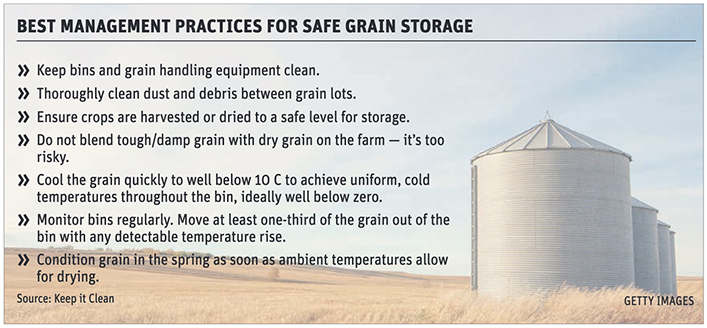

Moisture and temperature are the two critical factors behind safely storing grain. Dry and cool are the two rules of thumb, but how dry and how cool?

In terms of moisture, the Canadian Grain Commission sets standards for grading and storage purposes, available online at its “Moisture content for Canadian grains” web page.

For example, dry for peas and fababeans is 16 per cent or less. Beans are slightly less at 15 per cent, while soybeans, chickpeas and red lentils need to be 14 per cent or less. Red lentils go into the bin driest, at 13 per cent.

As for temperature, Barker writes that the target for all grains is 15 C.

Unfortunately, there is no such thing as “set it and forget it” with stored grain.

As weather conditions change, so do conditions within bins. As winter arrives, cold air moves downward along the outside of the bin, pushing warm, moist air through the core of the bin. This can cause high moisture areas to form where spoilage can get a foothold, with potentially disastrous results.

The Canola Council of Canada’s online Canola Encyclopedia advises growers to monitor bins closely until they are fully emptied.

“When stored canola temperatures plateau or begin to rise while outside air temperature cools through the fall and winter, be on guard for an increase in spoiled grain, as this is common in this scenario. It only takes one small hot spot to start a chain reaction that can spoil a whole bin.”

This is one area where moving the grain again to break the heating cycle is warranted for both canola and pulses. For both, the recommendation is to move one-third of the bin’s volume to get things stabilized.

As for cereals, while they may endure handling better than most crops, they are still susceptible to hazards in the bin. Keep it Clean, which keeps tabs on export market risks, flags a naturally occurring soil fungus, Penicillium verrucosum, as one of these. Under high moisture conditions, the fungus can proliferate in stored grains, producing ochratoxin A (OTA), which can make the grain unsuitable for export or un-saleable entirely.

The key is to cool grain as quickly as possible — Keep it Clean recommends a target temperature of well below 10 C — and doing frequent bin checks to ensure no hot spots.