Flat clay soils on the Regina Plains and the Red River Valley share a common complex problem. Both landscapes are perplexing for agronomists trying to make good nitrogen rate recommendations.

Saskatchewan agronomist Lee Moats faces the same challenge as that faced by Manitoba agronomist Brunel Sabourin in his Antara Agronomy CropPro franchise at St. Jean Baptiste, just south of Winnipeg.

When gathering data for nitrogen prescription maps, Antara, an independent agronomy firm, contracts with CropPro to have fields logged using the Croptimistic SWAT box. SWAT stands for Soil, Water and Topography. SWAT maps are high-resolution soil foundation maps used to build variable rate fertility maps.

Water has the most influence on yield and fertilizer response, according to CropPro’s website.

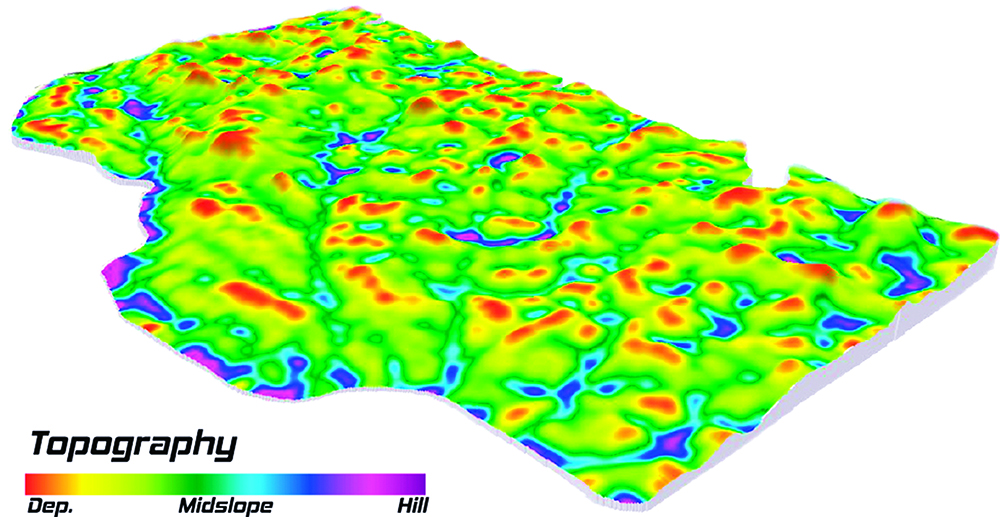

Topography describes landscape positions according to hilltops, mid-slopes and depressions. Topography influences soil moisture and soil fertility levels. SWAT maps sort dry and wet areas into 10 management zones.

“The challenge in making variable rate work is that so much variability depends on rainfall. It’s hard to determine the fall before how much it’s going to rain and when,” said Sabourin in a phone interview.

“Our window for applying variable rate fertilizer is in-season once we have our crop in the ground. Then we go in and top dress various areas of the field where it’s needed. In a drier year, our low-laying areas hold more moisture, so they get topped up. In a wet year, it’s our higher ground that gets topped up. By higher ground, I mean ridges that are two or three feet higher, maybe even five feet higher.

“The time gap between fall and spring is our biggest challenge in trying to make variable rate work around here. And we have a problem in-season trying to get in there to top dress fields.”

Sabourin said they try to have 70 to 80 percent of fertilizer down before planting is finished. Then in May they analyze conditions and decide what to do. He said holding back 20 or 30 percent is a risk management tool. Rain is necessary to wash nutrients down into the soil. If there’s no rain, there’s no further application.

“We still use prescription maps, but I don’t have any concrete numbers on how well they work because of top-dressing. We might boost the whole field average by five bushels by top dressing in just some areas.

“The more we play with variable rate, the more we realize that water drives yield. We have some clients who’ve been trying the SWAT system for three or four years now, but nobody is totally tied into the system so I can’t really comment one way or the other.”

The Antara website summarizes the need for prudent nitrogen management.

“Farmers have moved from the $25 blackjack table to the $100 blackjack table. Commodity prices are up but so are machinery, inputs and other expenses. Same game with higher stakes.”