Farmers are moving into the second decade of the post-Canadian Wheat Board monopoly marketing environment and appear to be spending little time looking back.

For those who have taken a moment to reflect, most report a decade of evolutionary change amid the tumult of weather crises, international disruptions and volatile world grain markets.

“It’s not easy to answer better or worse about the situation now,” said Brett Halstead, a Nokomis, Sask., farmer and chair of Sask Wheat. “It’s different.”

Related story: Farmers, wheat market have evolved since CWB demise

Read Also

New coal mine proposal met with old concerns

A smaller version of the previously rejected Grassy Mountain coal mine project in Crowsnest Pass is back on the table, and the Livingstone Landowners Group continues to voice concerns about the environmental risks.

The unravelling of the complex web of influences the CWB’s monopolies had upon western Canadian agriculture and food has affected every aspect of farming, from when and how a farmer can price and move his “board grains” to when he gets paid, to which varieties he is encouraged to seed.

It’s difficult to pull out separate strands of the web to examine each of them independently. When something is so large and all-encompassing as the monopolies, it’s hard to observe its impact in isolation, even though it suddenly disappeared on Aug. 1, 2012.

“It had all kinds of different effects. It was so pervasive on everything in the supply chain,” said Ryan Cardwell, an agricultural economist at the University of Manitoba, who is studying the farm-level impacts of the disestablishment of the CWB monopoly powers. That makes it challenging to show any simple effect, such as the impact of the wheat monopoly on the value of wheat.

“So many things changed and we’re trying to pull out an average effect on wheat relative to canola,” said Cardwell, noting the impact of initial payments, the government financial guarantee for the CWB, and the broad regulatory differences that governed board grains compared to non-board.

“They all have different effects in different directions and what we’re trying to get is the average.”

That challenge has faced and enticed numerous academics, who have looked at monopoly impacts from many angles pre-2012 and post-monopoly.

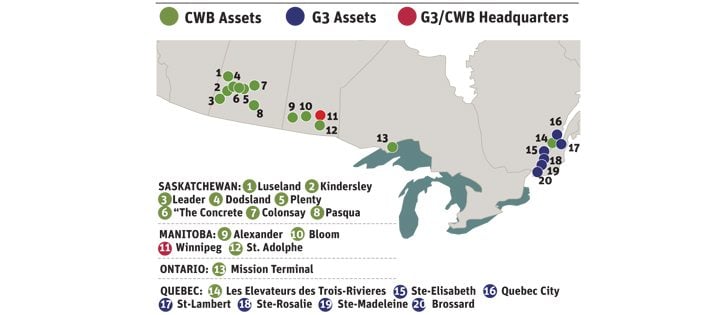

There has been much change in the western Canadian grain industry post-2012. New grain companies have arrived from overseas and south of the border; new terminals have been built in Vancouver; loop-track systems are allowing shuttle trains to chop days off traditional turnaround times and the railways have poured money into expanded capacity.

“There has been a great deal of investment, on all levels, in the transportation and handling system,” observed Barry Prentice, a long-time University of Manitoba transportation systems expert and analyst of the complexities of the western Canadian grain handling system.

“Much of that probably wouldn’t have occurred if the monopolies had stayed in place.”

Grain companies jumped on the chance to control grain from the point of purchase (the farmer) to the end-use customer. Railways were happy to see an end to the CWB’s ability to influence how they ran their systems.

Prentice said the best summary and analysis of the recent evolution of the prairie grain handling system is by Quorum Corp. President Mark Hemmes, the federal grain monitor, in his 2021 paper “25 Years of the Grain Handling and Transportation System: a Time of Great Change.”

In it, Hemmes concluded the partial deregulation of the grain handling system, including the ending of Crow Benefit rate restrictions in 1995 and the CWB monopoly elimination in 2012, provided the impetus that has allowed the system to grow from annually handling less than 50 million tonnes of crop to today’s over-70 million tonne average.

The end of the monopoly powers provided the incentives needed for the latest wave of investments.

“With those constraints lifted, the industry moved forward with operational changes,” wrote Hemmes.

“Grain companies moved forward with completing the shift to a pull logistics approach and established marketing desks to handle the wheat, durum and barley crops. Management of the logistics of grain movement became more efficient with the grain companies now having complete control over the management of their assets in the country and at port.

“Producers, who were limited in how they sold their grain, were now working at gaining a better understanding of how the marketing system worked and how to best manage themselves in the new environment.

“Ultimately, the new investment in the system began to flow at an unprecedented level with new elevators, increased storage and improvements to the efficiency of the port terminals. It also brought new players to the industry, both foreign and domestic.”

The perspective for farmers turns the telescope the other way, from Hemmes’ on-high systemic impacts focus to localized effects at the farmyard. For every farm it’s been different, and every farmer interprets that impact differently. Prices, cash flow, favoured varieties, financing and storage were all affected by the shift from a monopoly system to the free market.

While true farmer sentiment is difficult to assess, there is little question that most farmers were apprehensive about the 2012 changes. Whether or not farmers were generally in favour of, or opposed to, the CWB’s monopoly powers, suddenly jolting the gigantic western Canadian wheat crop and the specialized durum and barley crops caused much consternation among farmers.

That year, 2012-13, saw an unprecedented bull market in grains, which helped farmers grab great prices and saw grain move down the rails readily as strong demand and less competition from drought-stricken U.S. crops allowed the crop to clear. But 2013-14 saw a dreadful winter of clogged, slow and broken rail movement, as a harsh winter hit the grain transportation system and farmers found themselves stuck with their grain and short on cash for months.

After 2014 grain prices fell into a weaker range than during the bull market and a dry cycle steadily bit into western prairie farmers’ ability to pull off bumper crops. For many farmers, agronomic challenges took over from grain-handling concerns.

The winter of 2020 saw rail interruptions from protests followed by the epic disruptions of the pandemic, then a new bull market, with another wicked winter in early 2022 as a chaser.

Where farmers have ended up today is partly due to the changes to the CWB monopoly, but most would probably attribute their farm’s success or struggles more to the impact of weather and local conditions than to any marginal improvements or damage to the grain marketing system.

One farmer who is happy today is Jeff Nielsen of Olds, Alta., who got elected to the CWB board of directors as an anti-monopoly candidate during its last years. He felt the monopolies were making it hard for him to profitably grow wheat and malting barley.

He believes the better markets he’s now finding for his CPS wheat and the direct relationship he has with malting companies wouldn’t have existed if the monopolies had been maintained, so he’s pleased with how things have worked out.

But on the 10-year anniversary date of the monopolies’ end, he didn’t try to organize a big public event to celebrate his side’s success, opting instead for an on-farm gathering with fellow Alberta open market supporters and some Chinese malt buyers.

“Everybody’s happy,” said Nielsen. “We’ve moved on.”

For farmers who opposed the breaching of the CWB’s monopolies, it was a grim anniversary, a tombstone in the graveyard of Canada’s orderly marketing history.

For most farmers it wasn’t much of a day of recognition at all. Farmers and farming have moved on and adjusted as the grain transportation, handling and marketing system have evolved.

And while much is different, one crucial element remains: dissatisfaction with the railways and the way that farmers often hold onto their crops for months every time a cold winter or extreme weather strikes.

“That hasn’t changed,” said Halstead. “That thing in the middle that moves it is still the big unknown.”

Old conflicts and issues may be fading with time, but farmers in the heart of the continent, far from tidewater and needing to get their grain across thousands of kilometres, mountain ranges and frigid winters, have no shortage of challenges to occupy them today and tomorrow.