The just-in-time delivery system has worked well for the country’s food sector, but COVID-19 reveals a significant flaw

Canadian farmers, the food industry and consumers are waking up to the reality that the “just-in-time” system works great — until it breaks.

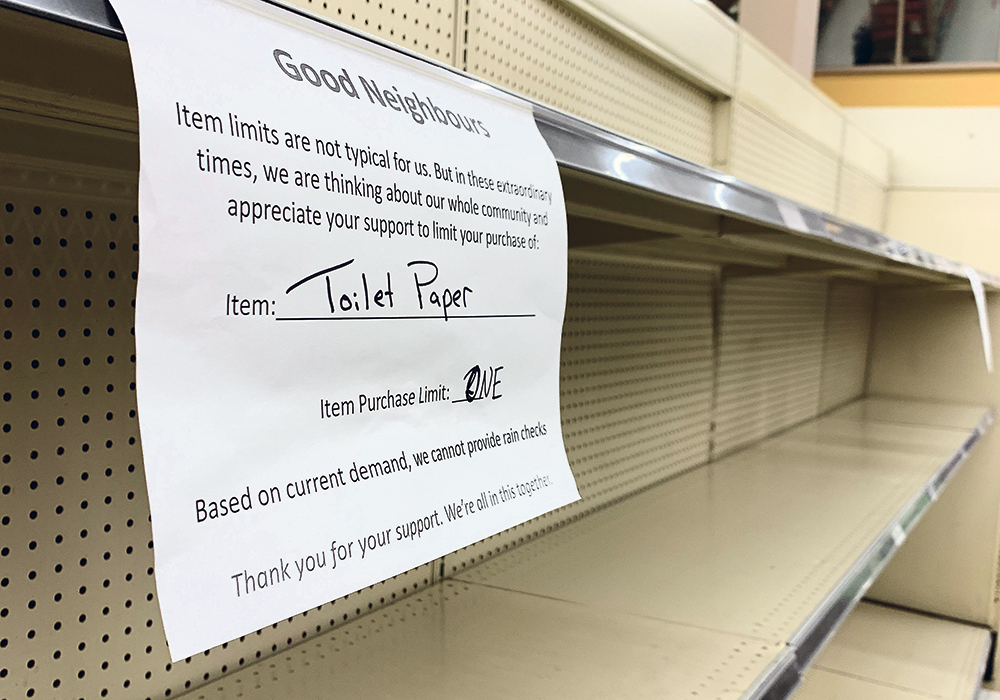

With farmers fearful about receiving necessary crop inputs for spring seeding, livestock producers terrified they won’t be able to move market animals, dairy farmers dumping milk and consumers finding they can’t find dairy products, toilet paper or flour on grocery store shelves, the COVID-19 crisis has revealed a deep flaw in Canada’s food production and delivery system.

“We have a co-ordination problem like we’ve never seen before,” said analyst Al Mussell of Agri Food Economic Systems.

Read Also

Canadian Food Inspection Agency red tape changes a first step: agriculture

Farm groups say they’re happy to see action on Canada’s federal regulatory red tape, but there’s still a lot of streamlining left to be done

“The benefit of a just-in-time system is that it cuts costs out and keeps down the cost of food…. When it really gets sideswiped, it becomes evident it doesn’t’ have a lot of redundancies.”

The term “just-in-time” arose from Japanese industrial production that radically reduced stockpiles and extra capacity in manufacturing value chains and lowered the cost of production of complex products like automobiles.

It was adopted by North American and European business leaders as a way of reviving their companies’ flagging fortunes after the 1982 recession and became the template for industrial organization for the past four decades. Globalization made it a worldwide phenomenon.

Canadian farming is based around the concept, with most farmers and agriculture interests never thinking about it.

Livestock producers assume they will be able to ship their animals to a slaughter plant when they’re fat. Growers assume they will be able to receive fertilizer and seed in the spring if they have contracted it.

Consumers have assumed they can always get everything they want from the grocery store, and that basic staples like flour and toilet paper will always be there.

Now COVID-19 has thrown all those assumptions up in the air. Slaughter plants are going off-line or slowing down as the virus infects workers or forces extra protective measures.

Transportation and logistics are getting tricky. Production of many products has become unreliable.

Toilet paper has become like gold.

It’s making for an anxious spring.

But even though the present crisis has revealed the system’s flaws, nobody should assume it will be radically overhauled any time soon.

“Most businesses are very careful not to overcommit to what they think the next reality is going to look like, just because the situation we are in is unique,” said Sylvain Charlebois, the senior director of the Agri-Food Analytics Lab at Dalhousie University.

“They’re not committing to long-term capital investments like building a new (processing line) just because people are baking bread at home.”

During the crisis, companies are boosting production as much as they can to meet surging needs, such as for bread flour for home baking, but changing the foundation of any large industrial operation or industry won’t occur until the confusion of this crisis has passed.

Other companies are trying to find new ways to configure their operations in order to meet emerging needs, and to replace a sagging mainline business.

Food service companies,which provide food to hotels, schools and other institutions that are mostly closed today, are trying to find ways to serve consumers who can’t find what they need from traditional businesses.

Restaurants are doing much the same, turning to delivery and curbside pickup to stay alive.

But permanent change doesn’t happen overnight.

Mussell said he has faced many questions about how Canadian agriculture supply chains can become less reliant upon just-in-time suppliers and buyers, but there is no easy answer.

“We don’t really stockpile things,” said Mussell.

“We’re not really set up to do that.”

Canadian crop growers already provide much stockpiling capacity. Most farms can store an average year’s crop in their bins, or close to one, and have fuel tanks and fertilizer storage that can hold much of what they need.

But once the COVID-19 crisis has passed, farmers will be left with questions:

What if this happens again?

What can I do to prevent that happening without crippling my finances?

“What would it look like and what would it cost?” said Mussell, summing up the challenge for farmers, the agriculture and food industries, and consumers on the other side of this crisis.