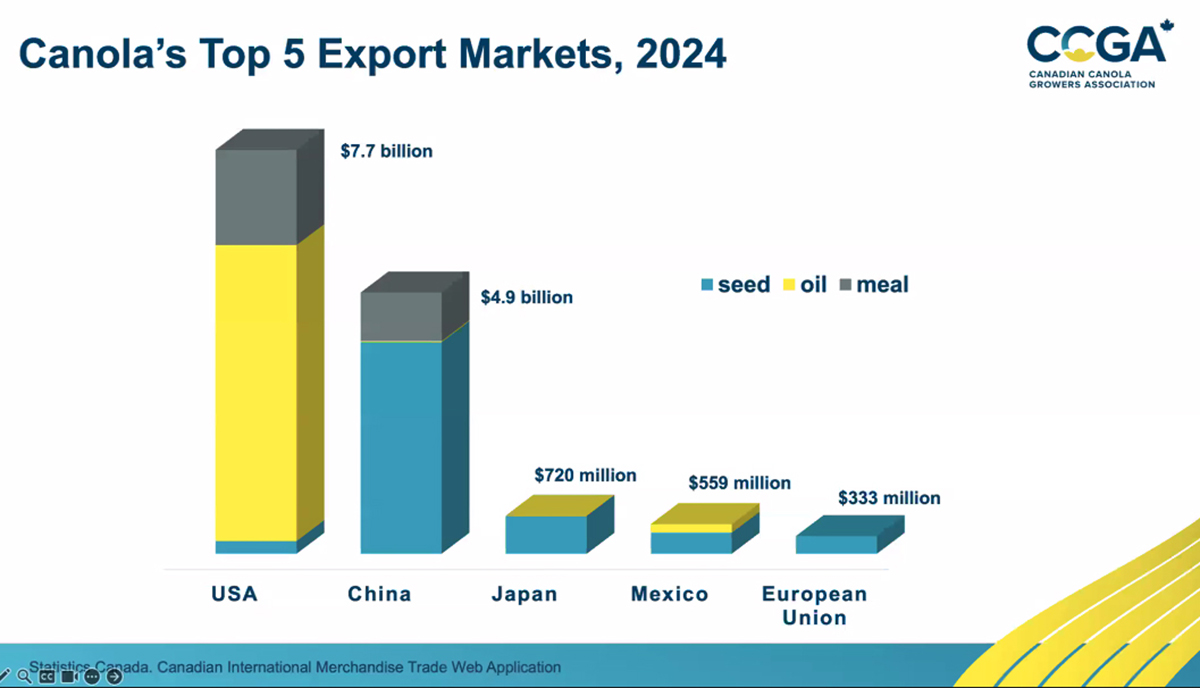

SASKATOON — Tariffs are threatening sales to two countries that purchased a combined 87 per cent of Canada’s canola exports in 2024.

The United States imported $7.7 billion of products last year, while China bought $4.9 billion worth of seed, oil and meal.

Some of those sales were placed in jeopardy when China implemented 100 per cent tariffs on Canadian canola oil and meal effective March 20th.

Read Also

New coal mine proposal met with old concerns

A smaller version of the previously rejected Grassy Mountain coal mine project in Crowsnest Pass is back on the table, and the Livingstone Landowners Group continues to voice concerns about the environmental risks.

China is also in the midst of an anti-dumping investigation that could see tariffs applied to Canadian canola seed in the coming months.

In the U.S. market, Donald Trump’s proposed 25 percent tariffs on a broad spectrum of Mexican and Canadian goods was scheduled to be implemented on April 2nd.

The tariff turmoil begs the question — where will Canada’s canola go?

One option is to look inward, said Brittany Wood, senior manager of transportation and trade policy with the Canadian Canola Growers Association.

Canada’s domestic market for the crop is already quite large, consuming 1.4 million tonnes of oil and 800,000 tonnes of meal in 2024.

There is room to grow those volumes substantially through a thriving renewable diesel sector.

Imperial Oil announced in January 2023 that it had approved construction of a $720 million renewable diesel facility in Strathcona, Alberta.

The plant, which is expected to be commissioned in 2025, will produce one billion litres of the biofuel annually.

Imperial’s facility will require one million tonnes of canola oil produced from 2.5 million tonnes of canola seed per year.

Wood said that is larger than Canada’s annual exports to Japan and Mexico combined.

She thinks there is a golden opportunity for Canada to foster construction of more of those plants if Ottawa gets its biofuel policy right.

“We need to see this market really be realized and come to fruition,” she said.

Chris Vervaet, executive director of the Canadian Oilseed Processors Association, said the industry needs long-term, predictable policy demand signals at both the federal and provincial levels.

“At the moment, we’re looking at a policy environment that isn’t as well defined as we’d like it to be in Canada,” he said.

Earlier this year, Federated Co-operatives Limited announced it was pausing its Integrated Agriculture Complex project in Regina due to regulatory and political uncertainty, escalating costs and shifts in low-carbon public policy.

The proposed $2 billion project included a renewable diesel plant capable of producing 15,000 barrels of the fuel per day and a canola crush plant that would have processed 1.1 million tonnes of seed, producing 450,000 tonnes of oil annually.

Wood said Canada needs a thriving domestic biofuel industry to support a canola sector besieged by trade wars and a shifting biofuel policy landscape.

The canola sector recently received devastating news that canola oil does not qualify for the vital U.S. 45Z biofuel production tax credit.

That is a huge blow because the rapidly expanding U.S. biofuel sector was responsible for about 1.5 million tonnes of new Canadian canola oil demand in recent years.

GrainFox lead analyst Neil Townsend said one thing to keep in mind is that Trump’s 25 percent tariff won’t completely tank canola oil sales to the food segment of the U.S. market.

Food companies are reluctant to change formulations because each oil has certain attributes and properties and any wholesale change would require loads of functionality and taste testing and of course new food labels.

“Definitely on the food side I think it’s very sticky,” he said.

Townsend said there are no real feasible alternatives to Canadian canola oil in the U.S. market, so while sales could take “a bit of a hit” it is unlikely to be complete devastation.

On the biofuel side he wonders where the U.S. is going to get the feedstock required given that imported used cooking oil also does not qualify for the 45Z tax credit.

“It’s hard to make the math work without some inclusion of canola oil,” he said.

However, Townsend said the U.S. and China might be able to replace canola meal in livestock rations because there are plenty of alternative feed ingredients.

One seed export market to keep an eye on is the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which has significant excess canola crush capacity.

“I would think we might be able to ship them quite a bit more because what they’ll do is repackage it and send it to China because now it’s from the UAE,” he said.

“I’ve heard they have much more capacity than they’re utilizing.”

The European Union is another market that could mop up some of Canada’s excess supplies. China is likely going to be purchasing more canola from Russia, Ukraine and Australia, which could create a void in the EU market.

The good news is that canola has not lost its luster. There will be plenty of global demand for the crop, especially if prices fall due to the tariffs, said Townsend. That could open non-traditional markets for canola.

The other bit of good news is that carryout from Canada’s 2024-25 crop is not expected to be burdensome.

And there could be yield challenges if the summer weather does not co-operate.

However, Townsend has still been advising farmers that this could be a good year to fallow some land or plant an alternative to canola.

He would like to see planting shrink to something like 17 million acres from last year’s 22 million, but that appears highly unlikely based on conversations he has had with growers.

“Nobody seems to be wanting to do that,” he said.