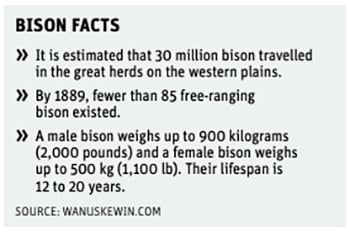

For thousands of years, the first peoples of the great western plains of Canada survived by fishing, hunting and gathering food from the land. The huge herds of bison that roamed the plains were their primary food source.

The bison were sacred animals for the Indigenous people, providing them with the necessities of life: food, clothing, shelter, tools and toys.

The people recognized that they could not survive without the bison. Each animal that was killed was efficiently butchered and everything was used from the sinew for thread and bow strings to the bones for tools.

Read Also

Alberta cracks down on trucking industry

Alberta transportation industry receives numerous sanctions and suspensions after crackdown investigation resulting from numerous bridge strikes and concerned calls and letters from concerned citizens

The scrotum was stuffed with bison hair to create a ball.

About 24 bison hides were required to cover an average tipi with a diameter of about 4.6 metres (15 feet), according to albertashistoricalplaces.com.

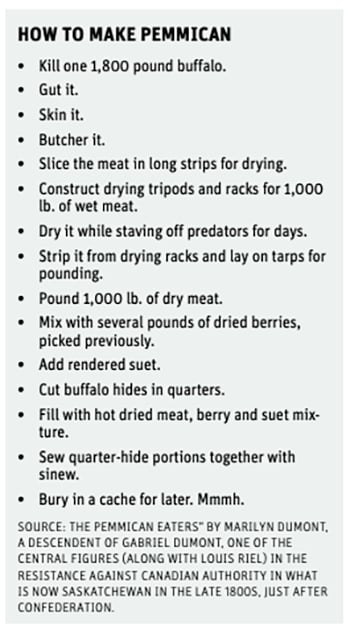

Some of the bison meat was eaten fresh, roasted or boiled, while the majority was dried.

It was cut into thin strips and hung on wooden racks in the sun or over smoky fires for several days to dry. Removing the moisture reduced the weight and preserved the meat, resulting in what we now call jerky.

The native people of the plains had learned how to process this dried meat further to make it easier to transport and store.

To increase the caloric value and flavour, dried ground berries, such as saskatoon berries and chokecherries, were added along with melted bison fat, to hold the mixture together.

The result was a nutritious, high energy, easy to carry and eat food.

Indigenous women took the time and effort to use only the best meat and the best tasting fats from around the internal organs and the leg bone marrow. This gave their pemmican a sweet flavour.

The pemmican mixture was stored in hide bags, with a final layer of melted fat to seal the contents. The bags were then sewn closed, making them waterproof.

In 1670, King Charles II of England granted a royal charter to create the Hudson’s Bay Company, under the governorship of Prince Rupert, the king’s cousin. The land became known as Rupert’s Land.

It gave the company and its merchant governors exclusive rights to trade and colonize all the lands containing rivers that flowed into Hudson Bay.

This included what is now northern Quebec and Labrador, northern and western Ontario, all of Manitoba, most of Saskatchewan, south and central Alberta, parts of the Northwest Territories, Nunavut and small sections of the northern United States.

At the time, almost no thought was given to the sovereignty of the many Indigenous peoples who had lived there for centuries.

The wealth of high-quality furs from the northern woodlands was the key focus of the Hudson’s Bay Company. It established trading forts and encouraged the Indigenous people to come and trade the pelts for blankets, beads, metal pots, guns and alcohol.

The fur traders realized that paddling and portaging loaded canoes took great exertion and energy, which their traditional diet of corn, flour, dried peas and limited meat didn’t satisfy.

Their Indigenous guides, on the other hand, seemed to have much more energy and stamina by eating only small amounts of their pemmican.

The company soon realized they needed to trade with the Indigenous people to secure this necessary survival food.

In his book, Pemmican Empire Food, Trade and the Last Bison Hunts in the North American Plains 1780-1882 from 2015, George Colpitts, an Alberta history professor, details how the HBC and other fur traders created a pemmican manufacturing industry on the plains to provide food for their expanding trade and exploration ventures.

Indigenous and Métis people were encouraged to hunt the bison for the sole purpose of making commercial pemmican. Hunting from horseback with guns made the hunt quicker and easier.

Unfortunately, the high demand for bison meat led to the removal of only the choicest and most accessible meat and fat, leaving the remainder to waste.

The quality of this factory produced pemmican at trading posts was much poorer than the traditional pemmican, as noted in Hudson Bay records, where complaints about bark from drying racks, hair and dirt were found in the trade pemmican.

The demand for pemmican led to over hunting and the near extinction of the bison herds by the late 1870s.

The creation of Canada in the East in 1867 led the HBC to surrender its land back to the British crown in 1869.

On July 15, 1870, this land became part of Canada, subject to the making of treaties with the sovereign indigenous nations. The new Canadian nation saw opportunities for expansion with settlers on the Great Plains and union with the British colony on the Pacific coast.

With the loss of the bison herds and the plans for settler expansion, treaties were made with the Indigenous peoples to give them reserve lands to live on and promises of food and tools. Unfortunately, many of those promises were poorly kept. Often, the food supplies were poor quality flour and fat, food similar to what the fur traders had rejected to replace with the superior Indigenous pemmican.

From the meagre rations of flour, fat and water, the Indigenous people created bannock, which they fried, baked or cooked over an open flame. It became their new version of survival food.

For many First Nations people today, it is a symbol of their resilience and unity, and it is shared at family gatherings and celebrations. Every family has their own unique way of making and using bannock.

Jodi’s best bannock

Jodi Robson is a proud member of the Okanese First Nation and is of Cree and Nakoda heritage. She lives in Regina, (Treaty 4 Territory).

She developed this bannock recipe “after years of observing kokums and aunties in their kitchens. Each made their recipe slightly different and not a single one of them measured precisely, nor shared their “recipe.”

Serves 12.

- 4 cups all-purpose flour (plus extra for kneading) 1L

- 2 tbsp. baking powder 30 mL

- 1 tsp. salt 5 mL

- 1/2 c. canola oil 125 mL

- 2 1/2 c. warm milk or water 625 mL

Preheat oven to 375 °F (190 °C).

In large bowl combine flour, baking powder and salt.

Make a well in flour mixture and add oil and warm milk into the centre. Slowly bring flour into the liquid with a wooden spoon until dough comes together.

Generously sprinkle additional flour onto clean surface, turn dough out onto flour and sprinkle with more flour. Knead dough until it becomes a smooth elastic ball (approximately five minutes).

Transfer dough to a parchment lined baking sheet and press out into an oval shape about one inch thick. Using the end of a wooden spoon, create dimples in the dough. Dip handle in flour if needed to prevent sticking.

Bake for 30-35 minutes or until golden brown. Serve warm or cooled with favourite jam or stew.

Adapted from canadianfoodfocus.org

Today, the bison herds are growing on ranches across Western Canada and the United States, and small bison herds are being established on native reserves.

Bison meat is now available in some restaurants and specialty meat shops. I found that Northern Meats in Spiritwood, Sask., carries it occasionally.

The great Northern Pains of Canada are now recognized as the traditional homelands of the Ininew (Cree), Anishinaabe (Ojibwe), Oji-Cree, Nêhiyawak (Plains Cree), Nahkawininiwak (Saulteaux), Nakota (Assiniboine), Dakota and Lakota (Sioux), Dene, Denesuline (Dene/Chipewyan), Siksika (Blackfoot), Kainai (Blood) and Piikuni (Peigan) and the traditional territory of the Metis.