PINCHER CREEK, Alta. — Two retired teachers are at last dealing with kids that don’t talk back.

There might be some teasing and running in the hallways or alleyways but that’s all in a day’s work on a goat farm.

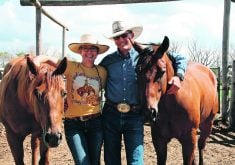

Tom and Catherine Sheard operate Mountain Sunset Angoras on the outskirts of Pincher Creek. About 90 goats, most of them purebred Angora, carry their valuable fibre around the 10-acre farm.

The Sheards began their operation 10 years ago with 10 does and a buck.

Read Also

Livestock leads Canada’s farm economic outlook

Forecasts by a major Canadian farm lender featured good and bad news on the financial health of both farmers and Canadians at large.

“We had a problem with sagebrush in the yard so to try and keep it down, I thought we’d get some goats. I don’t know why it struck me to get Angoras, but that’s what we got,” said Tom.

The does in the original purchase weren’t supposed to be pregnant, but when two of them had kids amid January’s cold, it forced some quick thinking and temporary installation of the chilled kids in the garage and the bathroom, he said.

Today, there are several barns and shelters, plus fenced areas using wooden pallets that have proven ideal for goat containment.

The goats are sheared twice a year in September and March, so on this fall day, their hair was long enough to plunge fingers into the ringletted softness.

Tom said Angora goat hair grows about 2.5 centimetres per month, so every six months shearer Dave Carlsen from nearby Fort Macleod is hired for the job.

Some of the hair will be taken to a custom woolen mill in Carstairs for processing, and some will be shipped to Texas, where Tom said prices are better for mohair.

The fibre is warm and durable, as well as fire resistant. The first two qualities make it suitable for knitted and woven items, while the latter once made mohair popular in upholstery fabrics and insulation.

“It’s not a big seller because it’s expensive. It’s $23 for a four-ounce skein, somewhere in there,” Tom said of sales for knitters and weavers.

Tom said the goats are easy keepers and manage well on the small plot of hilly land near the creek.

“The creek is a natural fence. They won’t cross it,” said Tom, adding that the goats don’t like to get their feet wet.

“I could probably run 500 head but my wife won’t let me. You’d have to buy hay in the wintertime, but if you get good quality hay, they won’t eat that much.”

He also discounts the oft-repeated idea that goats will eat anything.

“All goats are browsers. They’re not really grazers. So out here, all the trees are trimmed off about this high,” he said, indicating a spot near his waist.

“There is a myth out there that goats eat everything, but they’re very picky. They won’t touch the dandelions.”

Angora goats are known for their fibre, which tends to mean a discount when it comes to marketing the animals for meat.

“We get less for the meat than we would from a so-called meat goat,” Tom said.

“Marketing is a problem not just with us,” he said.

It might improve “as there’s more people coming in from Eastern Europe and the Middle East.… There’s more goat meat eaten than there is beef in the world.”

Catherine has fallen in love with the Angora fibre, as their home illustrates with its myriad of dying, spinning, knitting and weaving projects.

Although she had some brief instruction in fibre dying, she is mostly self-taught in that art and is constantly experimenting with different dyes, knitting and weaving projects.

She uses acid dyes that provide colour consistency and colour fastness, and an array of casserole dishes serve as the vats.

“I like it to have a little bit of life,” Catherine said. “It’s not like a commercial (skein), so the mixing of the colours to me is important as I’m doing it.”

She has created items with “secret messages,” which are knitted items dyed with words and designs, then unravelled and knitted again so the message is contained but unknown to all but the knitter, and perhaps the recipient.

“Catherine has become a real artist when it comes to dying,” said Tom.

Catherine is modest about her colourful and mohair-soft items. She and Tom attend a few Christmas craft markets and a few other events to sell fibre and hand-made items, but selling isn’t a priority, particularly when it would be hard to price items to compensate for the hours of labour.

“I think if you really got into it, that you could go somewhere, but at this stage I don’t think I’m going to do that. This keeps me interested,” said Catherine.

“I keep finding new stuff to do and it’s just getting back to that time of year where I can pull in and do some of my kind of things.”

The couple settled in Pincher Creek after teaching in places like the West Coast and Calgary. They had friends who lived in the area, and family who lived in Saskatchewan and Manitoba, so they used to pass through southern Alberta frequently as visitors.

When it came time to retire from teaching, the climate and proximity to friends and family made the small town a logical choice.

Within the near future, they plan to sell their Angora goats. Tom, 86, said the chores are too physically demanding and he also thinks the property may be the site of a new access road off Highway 3.

As he tended the goats and stood while a tame “bottle baby” goat nuzzling his pant leg, Tom reflected on the education system in which he and Catherine spent their professional careers.

“If the (education) budget has to be cut, the first thing that goes is music and the arts,” he said.

“I knit my own mitts. I knit scarves. But the school system dumps the arts and the crafts in the first (budget cuts) of things that are not taught. They all want to teach painting, but they should be teaching kids down in Grade 3 how to knit and crochet, and I don’t mean the girls only. The boys should learn how to do it too.

“It’s just the idea that you’ve done something and you’ve done it yourself, a sense of accomplishment.”