On the Farm: A desire to get off the road and be at home more prompts a move into a completely different direction

Alida Prins was so afraid of bees growing up in Edmonton that she became terrified if she saw even one of them.

She now helps look after more than 2,000 hives that collectively contain nearly 100 million bees.

“Me being a beekeeper, to my family, is like the most ridiculous thing,” she says.

“I was a flailing, screaming kid that refused to sit outside if she saw just one bee … everyone can relate — everyone has that kid. That was me.”

The unlikely path to Alida becoming a beekeeper started when she was about 14 years old. Her mom was a cook at a Christian camp for people with disabilities near Gull Lake, Alta., west of Lacombe.

“And I remember coming out with her one time to help and I was like, ‘this is the most amazing place. I’m going to marry a farmer out here and I’m going to be a farmer’ — and I literally married the farmer.”

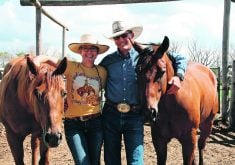

Her future husband, Lorne, lived with his parents on a farm just down the road from the camp. It’s not far from where he and Alida are now raising their infant son, Owen, and running the Gull Lake Honey Co.

However, the couple didn’t meet until they were briefly students at a private Christian college in Edmonton.

“We were acquaintances,” she says. “We knew of each other. That was it.”

Lorne decided to leave to study business and trades at a polytechnic school. Alida got a job in administration at a union, where she worked for 13 years with Lorne’s brother.

As a journeyman welder in the oil and gas industry, Lorne became a union steward and then moved up into management. She would deal with him when he called to book training courses for his workers.

Things moved beyond the acquaintance stage and the couple married in 2017.

“But yeah, that was a long, sordid affair,” says Alida with a laugh.

Lorne likens their 360-degree decision to drop everything in 2018 to become beekeepers as a kind of marriage, too, even if it was what he describes as an arranged one.

“It kind of fit what we were looking for, and then we fell in love (with it) later.”

After becoming a general superintendent with an eye toward international construction management, Lorne’s career started taking him as far away as China. But when he married Alida, things began to change.

The thrill of what had been his dream job began to fade due to weeks-long separations from his wife. The couple were also looking at starting a family and Lorne wanted their children to have the same experiences he did growing up in rural Alberta.

He began thinking about returning to his roots in agriculture, “but grain farming now is so capital intensive, it’s almost impossible to come back home and start from scratch, right?

“There’s a lot of competition for land around here and it’s so expensive, so that was kind of out, and dairy farming, it didn’t fit.”

However, Lorne had connections to beekeeping through an uncle, along with a friend of his parents. Both beekeepers wanted to downsize, “and they put it out there that hives and territory would be available … and then we just pulled the pin, we quit our jobs, and walked away from everything we had built, and just started here from scratch.”

Alida says it was a harder choice for her than it was for Lorne.

“He’s used to big moves and bold changes and his family had, you know, you’d seen his dad go through multiple different farming operations.

“And I grew up in the city and my dad was a carpenter, my mom was a stay-at-home mom, and my entire family lives within like a mile from my parents. And so big moves and big changes were a lot scarier for me, but I just kind of went along for the ride and before I knew it, I decided I liked it.”

Although Alida had been stung by a wasp, she’d never been stung by a honeybee. Both she and Lorne didn’t even know if they were allergic to bees when they obtained their first 100 hives.

“So, we both had to get stung and determine if it was going to kill us, and it didn’t, so then we’re like, ‘OK, this is it. We’re beekeepers now.’ ”

During the first two years, the couple essentially worked for free as apprentices to Lorne’s uncle, who taught them the ins and outs of beekeeping, says Lorne.

“And then in short order, we’ve reached out to our other commercial beekeeping neighbours and established some good friendships, and we’ve just grown from there.”

Five years into their new career, Lorne is now the vice-president of the Alberta Beekeepers Commission, balancing that role with his work at Gull Lake Honey Co.

He and Alida have based their operation on his parents’ remaining half section of land, where they sell everything from honey products to beeswax candles at their on-farm store, along with outside products such as bison meat.

Besides a market garden, they have a petting zoo and conduct field tours for home-school groups, says Lorne.

“We do open farm days, we host local artists and craft markets in our honey house, and we’re really utilizing our facility to generate as much traffic as possible just to share the industry with as many people as possible.”

It’s work that he and Alida enjoy. As an office worker for 13 years, Alida remembers looking outside when the weather was gorgeous. “And you think, ‘Oh, I just want to work outside.’ And now I do. It’s great. I love it.”

However, Lorne adds that stress can be an occupational hazard for beekeepers whose “livelihood is tied up with millions of insects (living) outside literally fending for themselves against the extreme elements in Alberta.”

Heat waves, drought and wildfire smoke last summer caused honey production at Gull Lake Honey Co. to decline to about 60 percent of what the crop would be in a good year.

Although the losses have been balanced by soaring honey prices, the tough summer conditions were preceded by last year’s long, early spring, resulting in high loads of parasitic varroa mites in hives across Canada during the fall, says Lorne.

“If you talk to a beekeeper right now, a lot of people don’t know if we’re winning or losing … and there’s a lot of very anxious beekeepers right now in regards to what type of winter losses we’re going to see. We will definitely have our highest winter losses this year.”

The bees at Gull Lake Honey Co. haven’t flown from their hives since October, and March is a pivotal month when their winter stores start to run thin, says Lorne. Opening the hives to check on their health would dispel the heat they’ve built up to keep them from freezing, he adds.

The fact Lorne comes from a farming background, and his parents still live nearby, has helped former city kid Alida deal with the ups and downs of agriculture.

“It helped immensely to just understand that those highs and lows happen, and that it’s literally a rollercoaster … one week, everything’s amazing, and then the next week, it’s bad weather and it’s terrible, and then it’s amazing, and (Lorne and his parents) get over it really quickly — and I’m still reeling from the last time things were terrible.”

However, Alida has long gotten over her fear of bees.

“A honeybee sting is actually so mild compared to that of like a wasp. Actually, you give yourself 30 seconds and the sting kind of goes away. It’s not that bad.”