Dairy farmers call it “star grazing” because their pastures twinkle with the green glow of health

The word “cropland” pops up when we think of satellite images used in precision agriculture. But an American dairy co-op uses Planet Labs PBC satellite images to manage 189,000 acres of organic pasture.

Organic Valley Pastures has 1,500 organic dairies spread across the United States, with 200 in their second season on the intensive precision ag style management system, averaging 180 grazing days per year with a 20 percent increase in pasture utilization.

Based in Wisconsin, Organic Valley Pastures is the first grazing organization in North America to apply precision ag technology to pasture management. OVP veterinarian Greg Brickner said he searched the continent to find somebody using satellite imagery to manage pastures.

“The closest experimenters we could find were in Australia and New Zealand, and they were doing it manually. So, three years ago we took the initiative and set out to develop our own high tech (precision ag) pasture management system,” said Brickner during an online interview.

“In New Zealand and Australia, they walk the paddocks carrying a handheld device to take measurements for an estimate of how much forage is in each pasture, and then they take this information and graph it. They rely on walking exclusively. The labour to create those measurements and enter them into a spreadsheet is very inefficient.

“Conventional pasture walking to monitor the quantity of vegetation has always been time-consuming and labour intensive. Which is why it often doesn’t get done. But satellite-enabled data sets can support a more efficient monitoring system. We’ve digitized rotational grazing.”

He said intensive rotational grazing in dairy is the same as in beef. Herds are moved frequently between divided pastures, leading to enhanced soil and water quality, carbon sequestration and improved animal health.

With precision ag, dairy farmers have quality data indicating the best time to move into the correct paddock. It’s no longer just moving from paddocks one through eight and then starting over again.

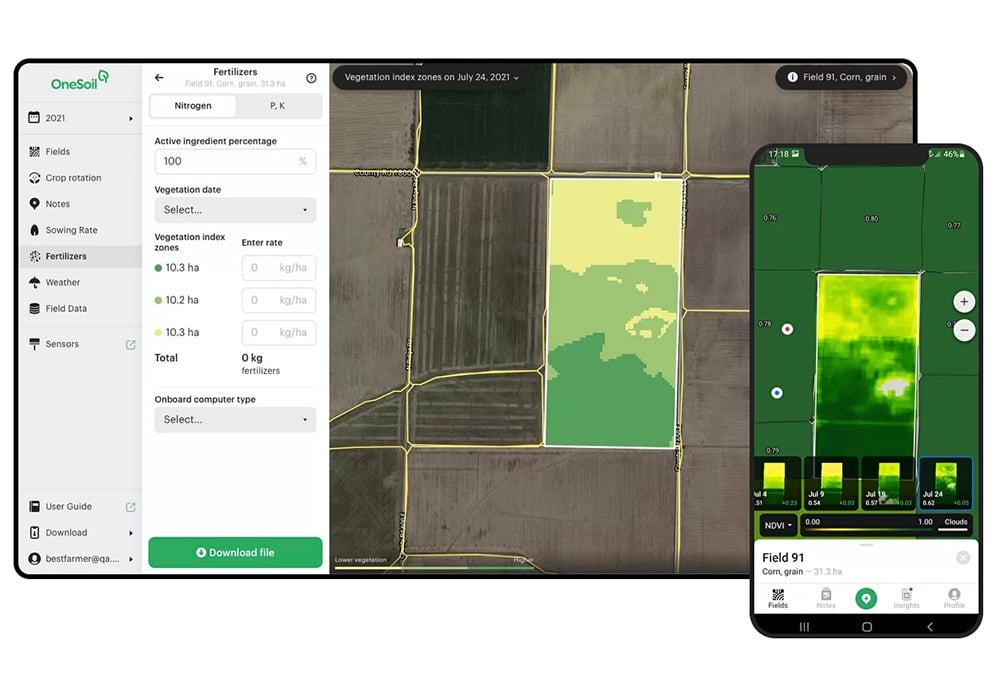

Brickner said they get their images directly from Planet rather than through an intermediary. They created their own programs to generate maps and automated reports, so there was no need to enlist a go-between.

“There’s a bunch of technology available using spectral images from either a drone base or satellite base to get estimates of biomass or dry matter in each paddock. This eliminates the need for the farmer to go out, which we know isn’t happening. We’ve been able to put quality information into the hands of our dairymen to let them make better decisions managing their perennial pasture. We skip over this labour input problem.

“Ground truthing was a bit of a glitch. It wasn’t like developing a system for cropland. Ground truth had to begin anew because there had been no satellites ever that created the kind of reports we need. We use Planet images, but they didn’t release their fleet until just recently. The old government satellites only produce two or three quality images during an entire growing season. Everybody’s had to start from scratch and make new measurements and do the calibrations.”

In calibrating the new system, Brickner used an instrument called a platemeter. This device measures available biomass. The data is compared to the Planet photo to establish a base line for using the images.

“We can create maps for any farm in North America. If we create a map in Planet, we can enter the boundaries of the farm and the paddocks within that farm, and get data specific to that smaller area. Now that it’s been working for two years, Planet provides a new satellite image every day at three square metres, barring cloud cover.”

Brickner said good grazers can develop management plans from observation, without precision ag data. But it’s often hard to determine the optimal time to put cows in the paddock. Is it ready for grazing in three weeks or four weeks? He said Planet provides grazing managers with scientific analysis, making them more proactive and less reactive.

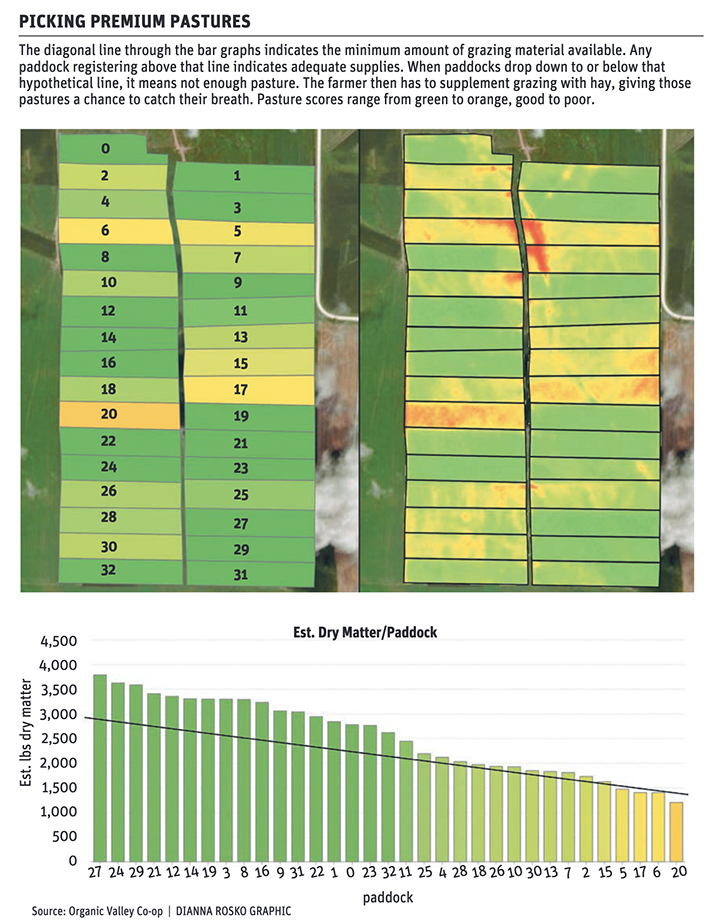

The system ranks paddocks according to dry matter biomass, depicted by the Y axis on the chart. Highest dry matter biomass is on the left. This will be the paddock cows will graze next. The paddock on the far right has the least amount of dry matter biomass, and is the one cows just grazed. Brickner wants to leave a minimum amount of green leaf so plants can regrow quickly. The X axis identifies each paddock.

The diagonal line indicates the minimum of grazing material available. Any paddock registering above that line indicates adequate supplies. When paddocks drop down to or below that hypothetical line, it means not enough pasture. The farmers then has to supplement grazing with hay, giving pastures a chance to catch their breath.

If paddocks are well above the line, it shows there’s plenty to go around, so the farmer can harvest the excess for winter feeding. Accurate assessment of available dry matter biomass is provided by the Planet satellite and the OVP system. Brickner said the satellite provides dairy producers far more detailed information than can be gathered by walking pastures diagonally.

Turning to the satellite photo, Brickner said the NDVI image on the left shows where fences had been years ago. It shows where cattle have been congregating, something the farmer may want to address. It also shows if there are places that should be re-seeded. He said the images show many factors that aren’t evident when walking in pastures.

“The image on the right is the red edge spectra. It gives more detail than the NDVI. We get better biomass detail. Red is either bare ground or brown plant material. That’s what the satellite sees instead of chlorophyll. You notice the edges are not as smoothed out as they are in the NDVI. The colour scales can be changed on any of the images. But in this shot, yellow and green do, in fact, depict better vegetation. And red depicts no active growth. We can create maps for any farm in North America using Planet imagery.”

Brickner said it’s easier to comprehend the image quickly when the image colours resemble reality on the ground. Red means dead. Yellow and green mean growth.

A claim of 20 percent increased carrying capacity comes from the Michigan State University Kellogg dairy research farm. Instead of satellite photos, they used drone photography to assess the impact of intensively managed dairy pasture.

“We know that about 30 percent of a cow’s ration comes from grazing. But that doesn’t mean you’ll see any increase in milk production. It means overall increased profitability of the farm. Supplemental feeding is expensive. If you offer cows better pasture, they’ll eat more forage and less of your expensive hay and corn and TMR (total mixed ration). That’s where your profit lays.

“Our more sophisticated members are using the system to extend the seasons at both ends. They graze earlier in the spring and later in the fall. That could be extended even further with forages designed for spring and fall.”

Brickner said that intensively managed pasture based on imagery doesn’t have to be confined to organic farms. It’s just as relevant in conventional dairies. Ranchers can also benefit.

“It could. I’d really like to see it available to them. It may not work in broad rangeland out West. But in the eastern third of the country, anything east of the Mississippi, they manage a little more intensively with their beef cows. This would be a huge help to them.”

He said the system became viable when Planet launched its 200 satellites, providing near-daily photos of each farm. Planet tries to schedule its daily photography between 11 a.m. and 2 p.m.

“These satellites are about the size of a toaster oven. They can be held in hand. They’re spread out across the globe. And they are situated so that their solar synchronous orbits fly from the North Pole to the South Pole.

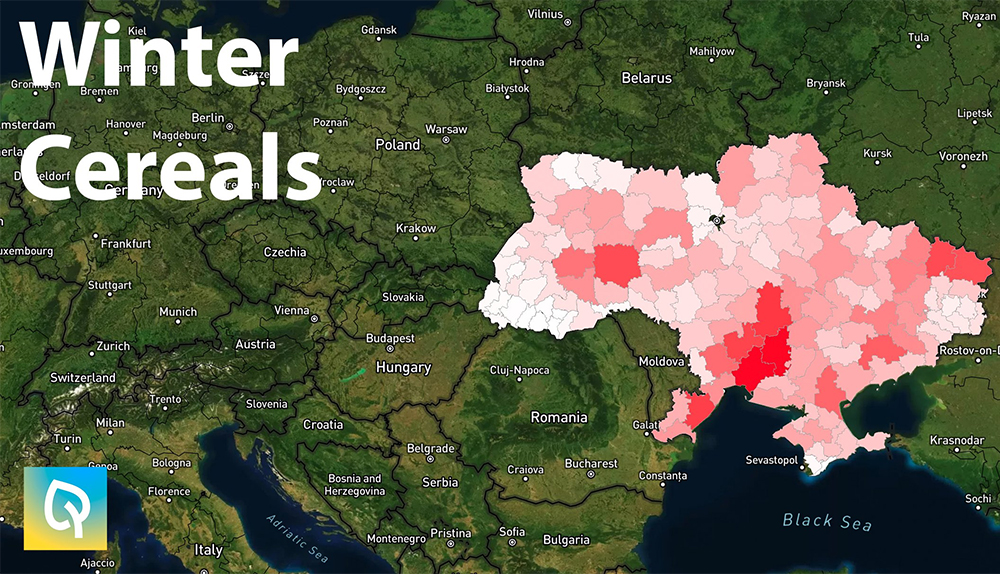

“Planet Labs is gaining some notoriety right now because they’re the only outfit providing accessible imagery of what’s happening in Ukraine.”