Canada’s canola sector is struggling to reach its goal of producing 26 million tonnes of the oilseed by 2025.

The current estimate of this year’s canola crop is 18.98 million tonnes, and the sector has failed to make much headway since posting the largest crop ever in 2017 at 21.46 million tonnes.

Other stories in the Canola Yearbook 2024:

- A new era for crop genetics

- Shrinking production estimate supports canola bids

- Canola growing season in review

- Canola remains a Prairie economic powerhouse

- Bill C-234 ping pongs between Senate and House

- Canola News Briefs

- Verticillium, blackleg and gophers

- Sustainability incentive for canola growers

- What made canola so strong?

- Science news briefs

- Tiny allies may help withstand drought

- Canola and climate change in Western Canada

- Production news briefs

- The future of gene editing in canola

- Canola views – photo essay

New crushing capacity is under construction, and when it comes on line in a couple of years, there could be a scramble for supply between the domestic industry and export sector if yields do not increase.

Read Also

Fertilizer method’s link to emissions studied

A researcher says others studying greenhouse gas emissions aren’t considering how the loss of nitrogen into the atmosphere correlates with fertilizer application or if there is an impact to yield.

Nevertheless, we should not over-emphasize the 26 million tonne goal because that is a massive increase that could overwhelm market demand.

The Canola Council of Canada’s bold growth goal of 26 million tonnes was set in 2014.

The group said several developments signalled the need for more canola from Canada.

The United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization predicted that the world’s need for food would double by 2050.

Canola’s health profile could help as cardiovascular disease and diabetes grew around the world.

There was a growing global demand for protein, and canola provides plant-based protein. It also noted new demand for canola in industrial uses and nutraceuticals. The council believed an aggressive sales campaign could capture an export market of 12 million tonnes and a domestic processing market of 14 million.

It expected the potential to expand seeded area to be limited, and set a goal of 22 million acres, which was about 6.5 percent more than the average at that time but has been reached several times in the last 10 years.

It was more aggressive with the yield goal that it set at 52 bushels an acre, a 50 per cent increase from the average in 2014.

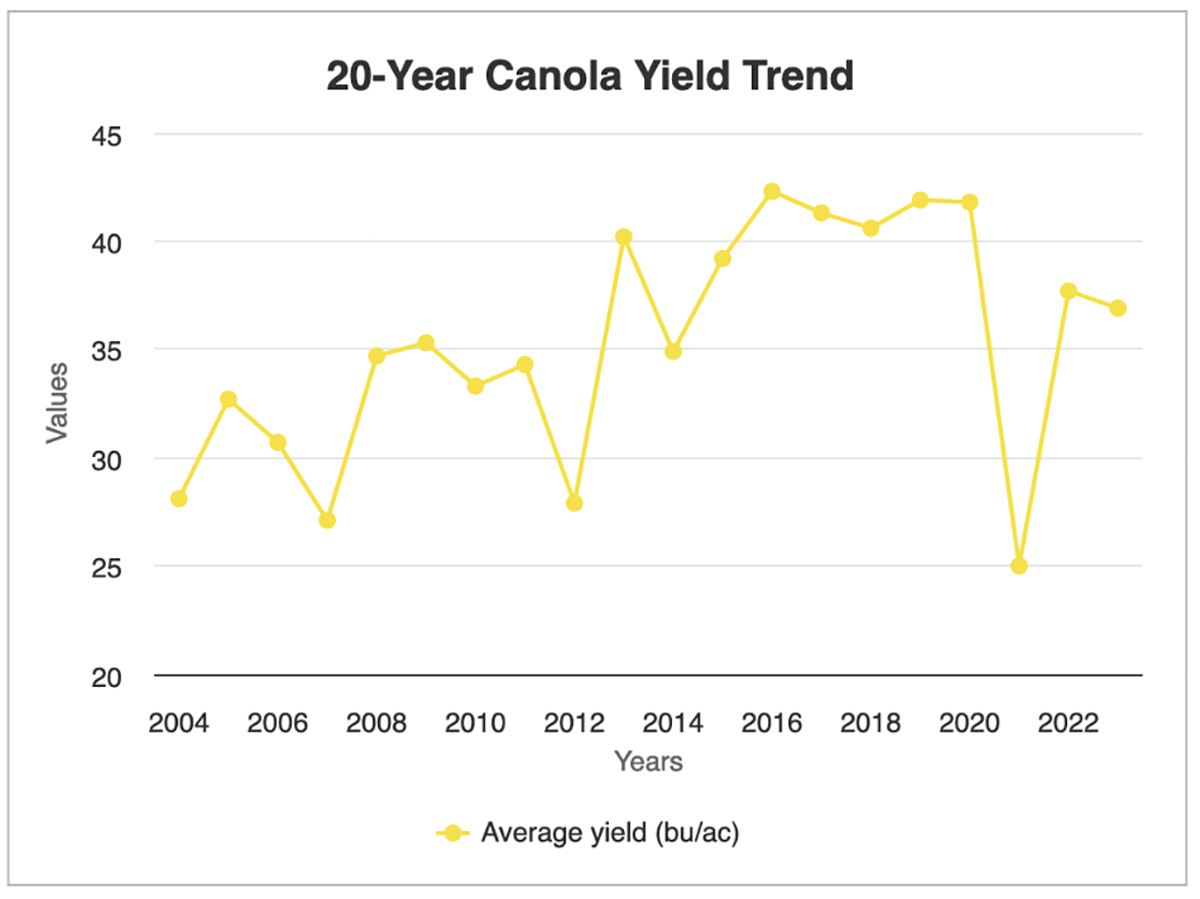

The yield growth from the average 2000-04 (25.26 bu. per acre) to 2010-14 (34.12 bu.) was 35 per cent.

However, yield growth has stagnated. The increase from the 2010-14 average to 2020-24 (37.3 bu.) is only nine per cent.

Indeed, the highest ever yield was in 2016 at 42.3 bu. per acre and has been significantly weaker in the last few years.

Granted, 2021 was a severe drought year, but average yields have failed to hit 40 bu. in each of the last three years.

A lot has to do with weather in recent years. Average wheat yields also appear to have struggled with the weather recently, failing to replicate the record of 54.8 bu. an acre set in 2017.

But generally, yields are failing to reach the top genetic potential of modern varieties.

A report in Canola Digest in August noted that producers might be under-fertilizing their crop.

It said that a 52 bu. per acre canola crop removes 130 to 220 pounds per acre of nitrogen from the soil.

However, average nitrogen rates for Canadian canola were 119 lb. in 2017-21, according to Fertilizer Canada grower surveys.

Of course, soaring nitrogen prices in 2021 and 2022 made fertilizer application an expensive task.

Nitrogen prices rose in response to the jump in crop prices and skyrocketing natural gas prices in 2021 and then from the market chaos following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in early 2022.

Other issues holding yields back are increasing problems with blackleg, rotations that are too tight, weed control that happens too late to get the best bang for the buck and inadequate seeding rates.

Agronomists suggest farmers try rotating varieties to see if a change in the type of blackleg resistance helps or perhaps using varieties that flower before the hottest days of summer.

Improving yields is a goal that often provides a more profitable crop.

However, we might also pause to question whether the goal of 26 million tonnes of canola is still the best idea.

If miraculously the 2025 canola crop grew by seven million tonnes to 26 million, I think it would overwhelm the market and crash prices.

The export market is still dominated by China, and it is an unreliable partner.

Its government has severely impeded imports from Canada for political reasons in the past and could do so again this year.

In the domestic market, there have been advances in processes to extract and use canola protein, but demand has not yet exploded higher.

The recent round of announcements of crushing plant expansions was mostly driven by the expectation that demand for canola oil as a feedstock for low-carbon renewable diesel and advanced fuel for aviation would increase.

However, demand for renewable fuel is mostly driven by government regulation, and that can change.

This summer, California, the biggest user of renewable fuel, proposed new rules limiting the amount of canola or soybean oil that can be used in its biofuel. It does not want to incentivize vegetable oil crop production to the point that it leads to plowing up of ecologically sensitive land.