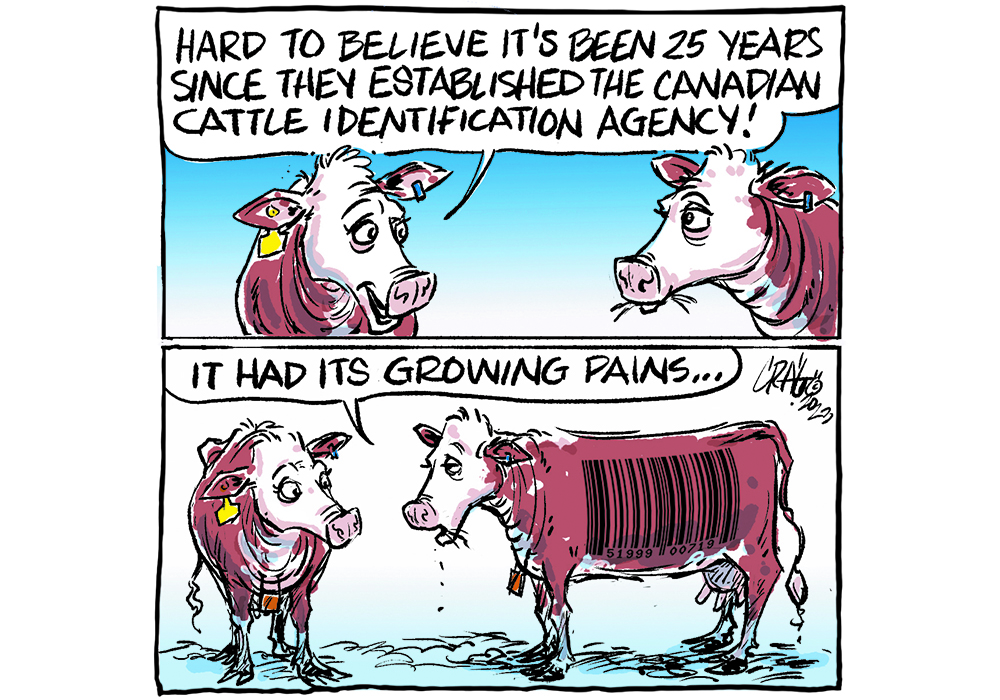

The move to traceability in the Canadian cattle business had a rocky start but now, 25 years later, it has proven out some of its early promise.

At first, producers feared banks, insurance companies, the Canada Revenue Agency and animal health companies would seek and obtain access to the data. Cow-calf producers would have to pay all the costs while the rest of the industry reaped the benefits, they feared. And what if tags were only used to prove ownership rather than for the higher purposes of traceability?

Read Also

Canadian farmers need new tools to support on-farm innovation

Farmers need a risk management buffer that actually works and investment that drives advancements forward if Canada is to build resilience.

Now the Canadian Cattle Identification Agency and the industry, including international buyers, take Canada’s ability to track and trace its livestock as a given.

The CCIA is doing what the cattle business intended it to do: make cattle identifiable.

National livestock identification programs weren’t universal 25 years ago, and still aren’t in many countries, including the United States. Canada chose to be a leader in this area, and it was a timely choice.

After rolling out as a voluntary program in summer 2001, traceability became mandatory the following July, by which time 95 percent of cattle were tagged and traceable before leaving the farm or auction market.

Then came the disaster of BSE. The traceability system aided the investigation of BSE’s origins and, maybe most importantly, gave consumers and some international markets the confidence to support Canada’s cattle industry.

Age verification was the only way to successfully export Canadian beef and cattle.

Today, premises identification seems like common sense in the face of zoonotic threats and global outbreaks of livestock diseases such as African swine fever.

The cattle tags themselves have also developed beyond the easily obscured barcodes. Now global standard radio frequency identification keeps the animals straight. Ultra-high frequency tags are also now accommodated by the CCIA, as it waits once again for the rest of the world to catch up. That technology allows groups of animals to be identified at a greater distance, which is a more producer-focused decision for the agency.

American farmers don’t have to tag cattle that remain inside their respective states, nor do cattle younger than 18 months require tags. That means only about 10 percent of American bovines require any identification.

The benefits of traceability to producers in the U.S. market come from packers, wholesalers and retailers who have found ways to profit by it, but only a portion of the industry takes part.

In the early days of Canadian traceability, producers were often told they would be able to access and use packers’ carcass data. With feedback on their herds’ genetics, they could develop feeding strategies and refine their production and profit by selling into market grids for quality and cutout.

A few such programs now run on value-based marketing strategies, but industry-wide deliverables to cow-calf producers mostly failed to materialize. Research is being done in this area today, including studies on lower-cost, objective and portable grading tools.

But the big producer benefit might come with larger amounts of data provided to seedstock producers through to retailers to identify the best, most efficient, sustainable and profitable animals. That was part of the original promise of traceability that is yet to be fully realized.

So far, no banks, insurance companies, the CRA or animal health companies have been able to access producers’ records and Canadian consumers can rest easy knowing animal health issues are a priority.

The tags that allow traceability are a cost to producers in terms of purchase and labour but with 25 years of hindsight, the benefits of the system to the industry’s reputation can’t be easily disputed.

Karen Briere, Bruce Dyck, Barb Glen and Mike Raine collaborate in the writing of Western Producer editorials.