As Glen Blahey packed his last boxes and passed on his final files, he looked back on a career that started on the fringes and ended up in the mainstream.

That trajectory of farm safety is something he can’t really divide from the trajectory of his own career because he was there for 35 years as farm safety consciousness evolved.

“It’s no longer whispered about off in the corner,” said Blahey, who has retired from the Canadian Agricultural Safety Association and who was interviewed as he cleaned out his office.

Read Also

Vintage power on display at Saskatchewan tractor pull

At the Ag in Motion farm show held earlier this year near Langham, Sask., a vintage tractor pull event drew pretty significant crowds of show goers, who were mostly farmers.

“More and more people talk about these issues.”

At one time, farm safety was mostly disregarded except for the obvious desire of most people to not be killed or maimed while living on a farm. But there was little training or education about farm safety, and many farmers accepted occasional accidents as part of the business.

In fact, some seemed to live a version of the Australian phrase, “if you ain’t hurtin’ you ain’t workin,’ ” Blahey said, remembering the early 1980s.

“That belief was there.”

Blahey grew up on a mixed farm in Manitoba’s Interlake region, but didn’t leave high school hoping to become a farm safety educator. There was no such job in Manitoba at the time.

He left school in Fisher Branch in the early 1970s hoping to become an industrial arts teacher, which he achieved after a couple years at the University of Manitoba. His old high school principal from Fisher Branch hired him, then asked him to help set up a vocational agriculture program. He did that, then went back to university to get a full education degree.

When he came out, there were no industrial arts teacher jobs available, so he worked odds jobs while he waited.

Then in 1981 came the job that gave him his career: agriculture health and safety officer with Manitoba’s labour department.

He began travelling through Manitoba talking to farmers and rural people, as well as trying to compile statistics on farm injuries and deaths, which was surprisingly hard to do.

At that time, farm injuries weren’t recorded as such, so they tended to get lost in overall provincial hospitalization data. He worked with health department people and managed to get farm injuries specifically noted.

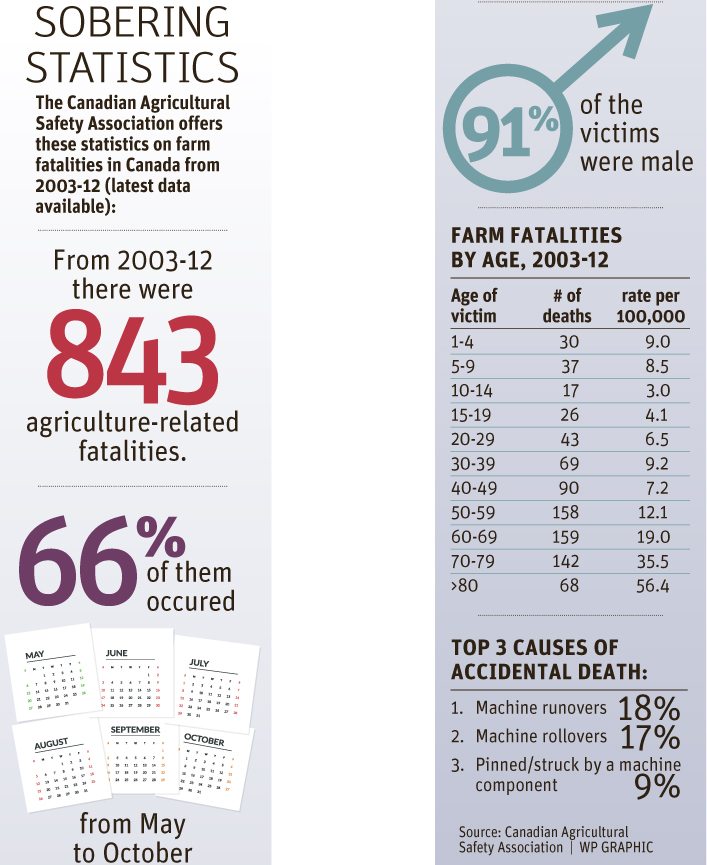

That led to lots of fresh, current data, and to decades of working with academic researchers to compile and analyze farm injury and death statistics not just across Canada, but also in the United States.

He and researchers found interesting phenomena, such as boys and girls having essentially identical injury rates until the age of six, but then sharply diverging, with boys getting hurt mostly by machinery and girls being hurt by animals.

That allowed farm safety people to customize education to families in a way that would be most effective.

Blahey said one of the biggest challenges he faced in the beginning was many men’s dismissive and resistant attitude toward farm safety. Often their wives were keen on keeping husband and family safe, so they seemed to enjoy attending his meetings, but many of the men sat “with arms folded across their chests.”

But as time has passed, men have become more open to understanding farm safety. Blahey said part of that might come from the perceptions around safety changing from a family-emotional-impact concern to one of business, economics and money.

“Farm safety used to be very much a personal issue, an emotional issue, a what-personal-impact-will-it-have-on-me issue,” said Blahey.

“That has (expanded).”

When farm operators began to realize that their farm could be ruined by injuries or death, they began to look at farm safety more seriously.

Blahey also had to overcome skepticism with farm management and government policy people. When the Growing Forward program was first being constructed, Blahey thought it should be funded.

“I said agricultural health and safety really is about business risk management,” said Blahey with a grin.

“I got a fair amount of pushback.”

However, with time, many in the farm management area began to focus on farm safety as a key element of farm financial sustainability and now it is often discussed as part of a holistic approach.

Blahey said he has seen a lot of good come out of social media, where farmers can get together to discuss issues that affect them. Often these days that involves mental health issues, and he’s glad to see those get better addressed.

Some of the statistics he saw over the years that struck him most were the ones revealing the high number of injuries and death that occurred during bad weather at harvest time. Some of the deaths appeared to be disguised suicides. That highlighted the complex interaction of farm operations, the weather and mental health in a way that was only beginning to be understood.

“Today, they talk about it as one of the challenges,” said Blahey.

However, he still has to fight back sometimes against the farming-is-different attitude that some farmers and people in agriculture proclaim, which seems to be a way of suggesting that safety can be taken more lightly on a farm than in other workplaces.

And he also worries about modern trends of free range parenting and a belief among some for experiential learning, which he fears could convince some to put aside formal safety training for hands-on experience.

But in general, he feels he’s stepping back from a field that has evolved from being a fringe concern to a central part of most farm families’ lives, and that’s an evolution he’s delighted to have witnessed.

“I have seen so much growth, probably more in the last 15 years than in the first 20,” said Blahey, taping shut a box.