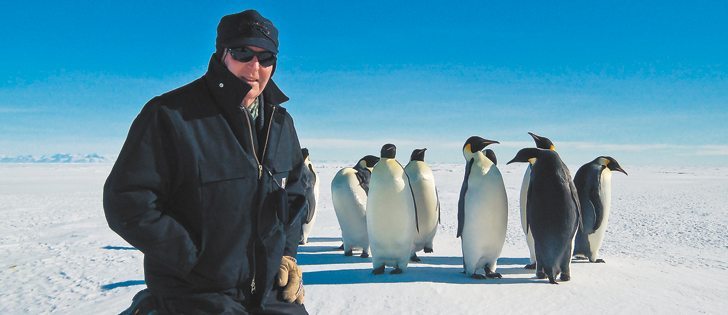

An Antarctic journey | Saskatchewan rancher recounts job at the world’s coldest, remotest spot

Ray Glasrud has enjoyed an inoperable condition all his life.

“I kind of always like to see what’s over the next hill. It’s a bit of a disease that never goes away,” says the adventure-seeking rancher.

Glasrud, who has spent time on all seven continents, recently returned from Antarctica. It was his third year employed as a heavy equipment operator for Lockheed Martin in the U.S. Antarctic Program.

Raised on a ranch near Mazenod, Sask., Glasrud graduated from the University of Montana in 1968 with a science degree in wildlife biology. His past work, much of it with the oil industry, has taken him to remote and cold places around the world.

Read Also

Farm auctions evolve with the times

Times have changed. The number of live, on-farm auctions is seeing a drastic decline in recent years. Today’s younger farmers may actually never experience going to one.

“The long and short of it was I’d gotten close to the North Pole but I’d never gotten close to the South Pole, but I’d always been fascinated by it,” he said.

Glasrud’s father first ignited the spark for Earth’s most southern continent in the 1950s. He remembers as a boy listening in as his father, a ham radio operator, talked and passed messages to U.S. and New Zealand bases stationed there.

“I remember sitting in the radio room and listening to these things and thinking, ‘wouldn’t it be nice to get there,’ ” he said.

Although Canada doesn’t participate in the Antarctic program, he said he kept looking for opportunities to travel to the frozen continent. The U.S. Antarctic Program, which represents the United States in Antarctica, strives to encourage international co-operation, maintain an active and influential presence in the region and conduct high-quality science research.

Glasrud, who recently turned 65, years, said the program doesn’t discriminate based on age.

“I didn’t know if they’d take an old guy, but I met certain qualifications and talked to them at length.”

He said he has been operating heavy machinery most of his life as well as flying planes for 40 years, which also included building winter airstrips. It was the combination of his science background and operator skills on track machines in the cold that got him the job.

“So I had experience in cold weather, I had experience in remote locations, I had experience with research. They wanted that because you have to associate with scientists,” he said.

Glasrud’s job required working at the Byrd Surface Camp, which is a deep field program 1,200 kilometres from “town.” McMertal Station, the main U.S. base, is also 800 km from the South Pole.

Glasrud’s primary duty was building and maintaining a 3,000 metre airstrip for the C100 Hercules airplanes that would land using skis. His main piece of equipment was a D4 Cat on tracks that runs on arctic jet fuel.

“The key to working snow is to move fast so that you create friction,” he said.

His other duties were varied when he wasn’t pushing snow.

“When you sign on with that kind of a research program, you could end up helping scientists one day, which I’ve done, you could end up helping the cook washing dishes. The next day you could be cleaning latrines,” he said.

Glasrud describes it as a place that fosters awe and respect.

“It is one of the most exotic, unbelievable places on the planet that I’ve ever been, and I’ve covered a fair bit of the old globe,” he said.

“It’s the windiest, the coldest, the most remote continent on the globe. It’s a harsh, dangerous environment in many respects. Even in the summer season, it’s 40 to 50 below zero with constant winds blowing.”

He said there are times when “your adrenalin gets pumping,” even with good planning, good logistics, lots of radio gear, satellite phones and survival gear.

Taking the advice of early Canadian explorers such as Vilhjalmur Stefansson, Glasrud said he never had adventures because he tried to plan properly.

“The weather can change dramatically in a heart beat. When you’re out there 1,000 miles from town, you want to keep your wits about you. We always had a medic with us but the chances of getting out of there if you had an emergency are pretty damn tight. We waited on this last occasion two weeks to get an airplane in. So if you’re sitting there with a broken leg, you’re going to sit there,” he said.

“It can get tremendous whiteouts where you just don’t see anything. I was familiar with blizzards and whiteouts, but I never saw whiteouts as bad as there, where you take a step and you can’t see what you’re stepping into. It’s like being inside of a milk jug.… The winds can change quickly, in a matter of minutes. So if you’re out doing something, you need to know how you’re going to get back, in what sort of time frame. And if there’s any question, you don’t go.”

Growing up on a ranch on the Prairies helps to an extent, he said.

“I like to think as a pilot, as a rancher and somebody who watches weather and has watched weather for years that I can kind of read weather, at least to some extent. There I am getting to the point where I can kind of get a feel for what the weather might do when you see certain clouds, but it’s so different that I really never did interpret it properly.”

One of the highlights for him came in November 2011 when he dug his way into explorer Robert Scott’s hut 100 years after Scott set out to discover the South Pole on his Terra Nova expedition. On their return journey, Scott and his four comrades all died from a combination of exhaustion, starvation and extreme cold.

“All of Scott’s stuff is still there. It’s amazing. When they found he had died, they just slammed the door and left. The food is still on the table,” he said.

Glasrud is also reminded of history back home at his commercial cow-calf operation, called the Pole Trail Ranch Company, between Shaunavon, Sask., and East End, Sask.

“When my grandfather homesteaded around Assiniboine, he followed the pole trail. The poles were from a telegraph line that had been set up to keep track of Sitting Bull when he was down at Wood Mountain. My grandfather came up from the States by railroad and followed that with a wagon along that telegraph pole line. They used to talk about it when I was a kid as the pole trail,” he said.

With three winters under his belt in Antarctica, Glasrud is itching for more adventure. Other horizons beckon, but he can’t help feeling a longing for the pristine, cold-blooded continent.

“There’s an old saying in the Antarctic. The first year you go for the money. The second year you like to go because you like the people and the third year you go because you don’t fit in anywhere else.”