It is painful to watch international trade hijacked as a political tool, rather than championed as an economic instrument to enrich the lives of citizens.

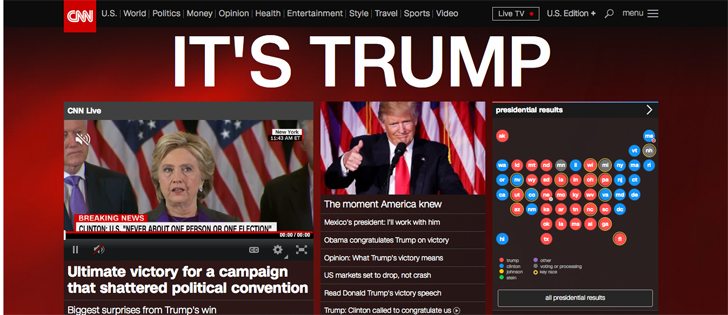

Even more so because of the rhetoric surrounding trade coming from United States President-elect Donald Trump, whose promise to renegotiate or rip up NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement) and kill the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement has generated chants of “down with the globalists” from rabid followers.

Trade has improved the fortunes of civilizations since the time of the Silk Road.

Read Also

Higher farmland taxes for investors could solve two problems

The highest education and health care land tax would be for landlords, including investment companies, with no family ties to the land.

But today’s trade agreements are intensely complex, and there is significant dispute about their effects.

As in many things, economists are not in agreement about the merits of unfettered trade as it is practised under major agreements such as NAFTA and the World Trade Organization. A chief contention is that trade agreements are structured to favour major investors and huge multinational companies that can shift their work easily among countries, resulting in heavy job loss in Canada and the U.S. Indeed, Belgium’s Walloonians, who almost scuttled the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement, protested that such agreements give corporations too much power over national sovereignty.

Economists argue both sides of this. Some argue that agreements have increased trade, creating higher paying jobs to replace those that are ultimately lost as a result of these deals, but other economists argue that trade deals have cost more jobs than have been created. (The Mowat Centre, an Ontario public policy think-tank, says Ontario has lost 300,000 manufacturing jobs over 10 years through automation, globalization, flexible exchange rates and low productivity.)

Reconciling these opinions is a divine task. Still, scrapping trade agreements is not the answer. We cannot make everything we want in North America.

U.S. economist and scholar Derek Scissors notes that “imports mean lost jobs only if we pretend we can make here all the things import, the same way, for the same price.”

And while it’s true that jobs are lost in Canada and the U.S. because of free trade, the jobs created in developing markets create a consumer class in those countries that ultimately buys Canada’s exports, though that is of no solace to those whose work has moved overseas.

Fortunately, agricultural trade brings benefits without the intense job displacement. Look at our exports: more than $55 billion in agri-food in 2015, up $9 billion from just two years earlier. Non-durum wheat, canola and lentils account for $13 billion alone. Agricultural trade between the three prairie provinces and the U.S. is more than $11.2 billion annually.

Growth in exports — and potential for more through the TPP agreement — fuels opportunity for Canadian farmers. The growth in canola is a prime example. Canadian farmers can take advantage of incremental improvements in yields due to the scale of their operations, and they can depend on a crop that presents reliable profits year after year.

Canada now exports $2.6 billion worth of canola seed and oil annually to China alone.

Trade rhetoric has turned ugly, but history has shown that when managed well and focused in the appropriate areas, trade improves the lives — economically and culturally — of parties involved.