WINNIPEG — It’s a mantra in the world of sustainable food — local is always better.

That rule doesn’t apply to peas, canola, wheat and likely other crops grown in Western Canada, say researchers from the University of British Columbia.

Their study, published in Nature Food, has concluded that Europeans could reduce greenhouse gas emissions from crop production if they imported peas, canola and wheat from Canada.

Read Also

Herbicide resistance sprouts in Manitoba’s wild oats

Farmers across Manitoba this fall are gearing up for the latest salvo in what, for many, has become a longtime battle to beat out wild oats.

“When SOC (soil organic carbon) was included, crops produced in Canada, then shipped overseas to Australia, France and Germany, still had lower carbon footprints than crops produced in each destination country,” say the authors of the study, which was published Aug. 5.

The greenhouse gas emissions from Canadian crops were significantly lower than European emissions for the same crops.

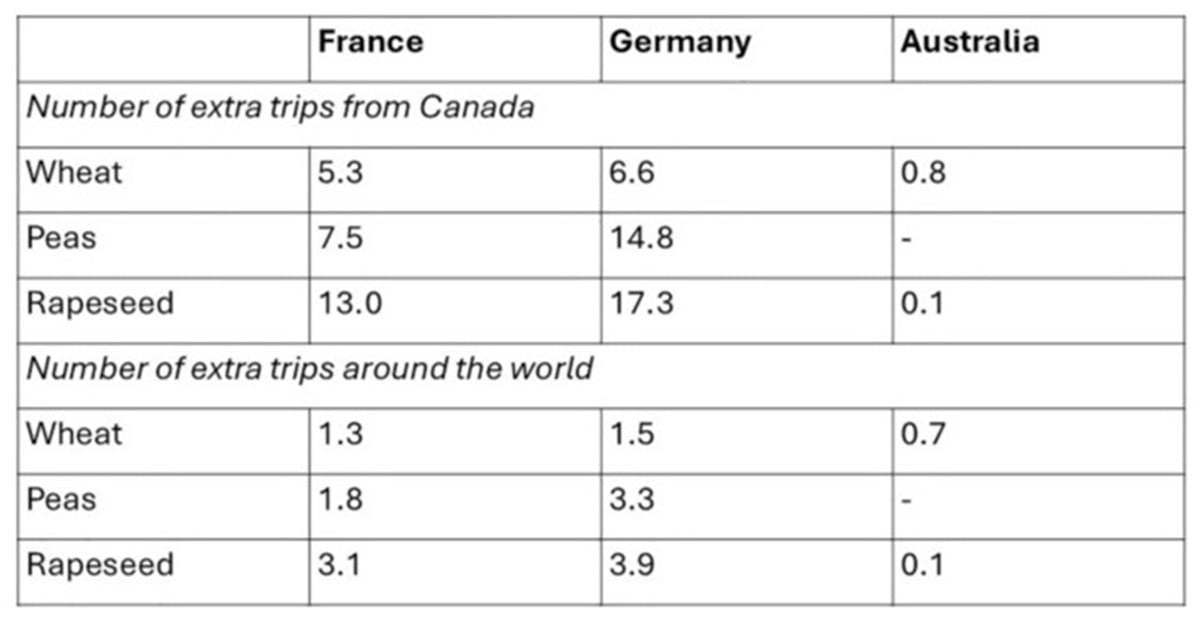

When the emissions from Canadian canola were compared to growing rapeseed in Germany, for instance, the Canadian canola could be shipped to Europe 17 times before the amount of greenhouse gas was equal to emissions from the German rapeseed crop.

“(That’s) equivalent to circumnavigating the globe more than three times,” the study says.

For Canadian peas, it could be shipped to Europe 14 times and still have lower emissions than a pea crop in Germany.

The authors of the paper were Nathan Pelletier, a UBC Okanagan associate professor who specializes in sustainability and food systems, and two post-doctoral researchers at the university, Ian Turner and Nicole Bamber. They are part of the Food Systems PRISM Lab at UBC.

Pelletier is the NSERC/Egg Farmers of Canada industrial research chair in sustainability. The study was funded by the Global Institute for Food Security at the University of Saskatchewan.

The researchers looked at several metrics to estimate the greenhouse gas emissions (in carbon dioxide equivalents) of canola, pea and wheat production in Canada and how that compares to other countries, including:

- Nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions from the soil.

- Changes in soil organic carbon.

- Fertilizer use and fertility management.

- Fuel use.

- Transportation to market.

“Generally, field-level nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions and soil organic carbon changes were the largest determinants of observed differences in carbon footprints,” says the paper.

“With SOC change included, Canadian crops always had the lowest emissions.… This is, in part, attributable to the widespread adoption of low- and no-till practices … along with conducive soil and climatic conditions and reductions in summer fallow.”

Increasing the amount of soil organic carbon, often called carbon sequestration, is an important metric of soil quality and a way to remove carbon from the atmosphere.

If the scientists didn’t consider SOC, growing canola, wheat and peas in Canada and shipping them overseas still generates fewer emissions than the same crops grown in Europe.

“Even when SOC change was excluded, Canadian crops had smaller footprints compared to the same crops produced in other countries,” the Nature Food paper says.

“Only Australian rapeseed was lower because of low field-level N2O emissions.”

European crops, in general, produce higher nitrous oxide emissions than Canada because the growing season is wetter and longer. In a dry growing season on the Prairies, western Canadian crops emit a small amount of nitrous oxide.

In drought years, such as 2021, N2O emissions are almost nothing, Richard Farrell, a University of Saskatchewan soil scientist, said in 2023.

As for transporting Canadian crops overseas, the burning of diesel fuel does produce greenhouse gases, but that amount is small when compared to the emissions from the field.

The UBC analysis shoots a large hole in the notion that local is always better in food production, at least for crops such as peas, canola and wheat.

“It is often assumed that local products have lower carbon footprints,” the paper says.

“This is not necessarily the case, particularly when there are large regional differences in resource efficiencies, production conditions and climate factors — even if transportation distances are large.”

The UBC scientists used emissions intensity to reach their conclusions about Canadian crops, which means they considered the kilograms of greenhouse gas emissions per kilogram of crop produced, rather than absolute emissions.

The UBC findings are similar to a study from the Global Institute for Food Security released in January 2024.

It found that crops grown by Saskatchewan farmers are some of the “least carbon-intensive” in the world.

“These impressive results are driven by the widespread adoption in Saskatchewan of agricultural innovations and sustainable farming practices that have significantly reduced the amount of inputs and emissions needed to farm each acre of land,” said GIFS chief executive officer Steve Webb, .

The 2024 study was done in partnership with UBC researchers from the Food Systems PRISM lab.